- Types of Sailboats

- Parts of a Sailboat

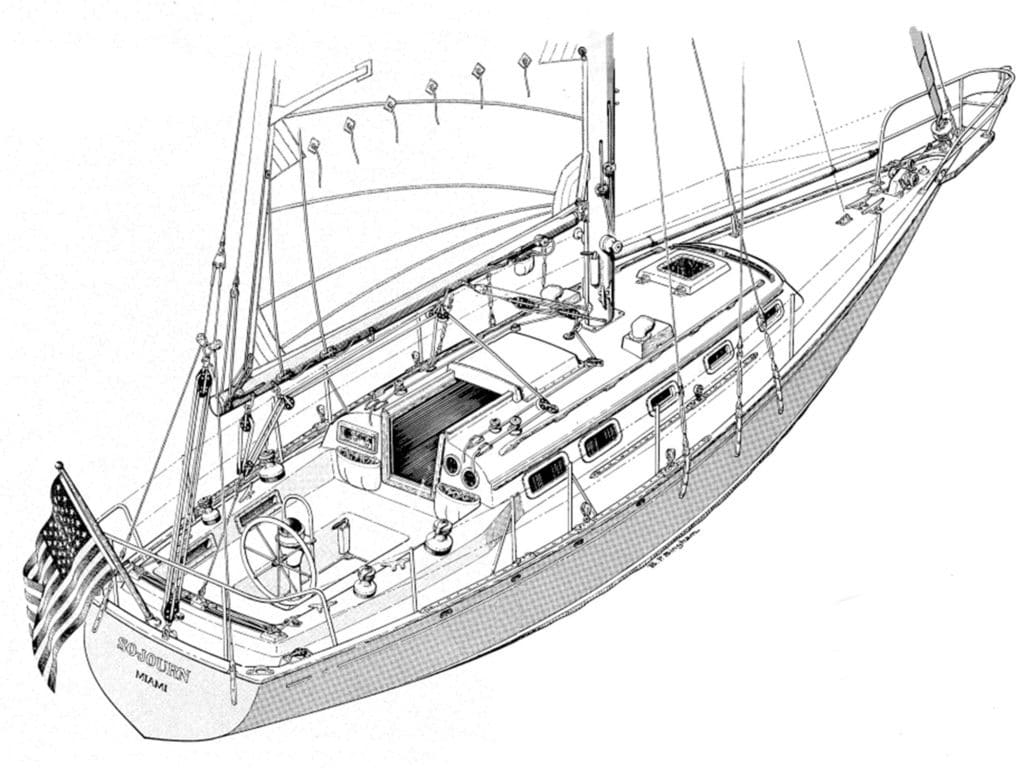

- Cruising Boats

- Small Sailboats

- Design Basics

- Sailboats under 30'

- Sailboats 30'-35

- Sailboats 35'-40'

- Sailboats 40'-45'

- Sailboats 45'-50'

- Sailboats 50'-55'

- Sailboats over 55'

- Masts & Spars

- Knots, Bends & Hitches

- The 12v Energy Equation

- Electronics & Instrumentation

- Build Your Own Boat

- Buying a Used Boat

- Choosing Accessories

- Living on a Boat

- Cruising Offshore

- Sailing in the Caribbean

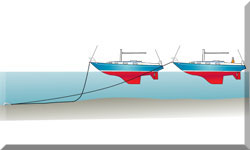

- Anchoring Skills

- Sailing Authors & Their Writings

- Mary's Journal

- Nautical Terms

- Cruising Sailboats for Sale

- List your Boat for Sale Here!

- Used Sailing Equipment for Sale

- Sell Your Unwanted Gear

- Sailing eBooks: Download them here!

- Your Sailboats

- Your Sailing Stories

- Your Fishing Stories

- Advertising

- What's New?

- Chartering a Sailboat

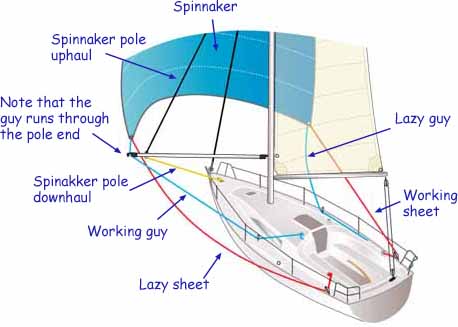

- Running Rigging

Sailboat Rigging: Part 2 - Running Rigging

Sailboat rigging can be described as being either running rigging which is adjustable and controls the sails - or standing rigging, which fixed and is there to support the mast. And there's a huge amount of it on the average cruising boat...

- Port and starboard sheets for the jib, plus two more for the staysail (in the case of a cutter rig) plus a halyard for each - that's 6 separate lines;

- In the case of a cutter you'll need port and starboard runners - that's 2 more;

- A jib furling line - 1 more;

- An up-haul, down-haul and a guy for the whisker pole - 3 more;

- A tackline, sheet and halyard for the cruising chute if you have one - another 3;

- A mainsheet, halyard, kicker, clew outhaul, topping lift and probably three reefing pennants for the mainsail (unless you have an in-mast or in-boom furling system) - 8 more.

Total? 23 separate lines for a cutter-rigged boat, 18 for a sloop. Either way, that's a lot of string for setting and trimming the sails.

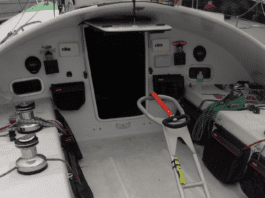

Many skippers prefer to have all running rigging brought back to the cockpit - clearly a safer option than having to operate halyards and reefing lines at the mast. The downside is that the turning blocks at the mast cause friction and associated wear and tear on the lines.

The Essential Properties of Lines for Running Rigging

It's often under high load, so it needs to have a high tensile strength and minimal stretch.

It will run around blocks, be secured in jammers and self-tailing winches and be wrapped around cleats, so good chafe resistance is essential.

Finally it needs to be kind to the hands so a soft pliable line will be much more pleasant to use than a hard rough one.

Not all running rigging is highly stressed of course; lines for headsail roller reefing and mainsail furling systems are comparatively lightly loaded, as are mainsail jiffy reefing pennants, single-line reefing systems and lazy jacks .

But a fully cranked-up sail puts its halyard under enormous load. Any stretch in the halyard would allow the sail to sag and loose its shape.

It used to be that wire halyards with spliced-on rope tails to ease handling were the only way of providing the necessary stress/strain properties for halyards.

Thankfully those days are astern of us - running rigging has moved on a great deal in recent years, as have the winches, jammers and other hardware associated with it.

Modern Materials

Ropes made from modern hi-tech fibres such as Spectra or Dyneema are as strong as wire, lighter than polyester ropes and are virtually stretch free. It's only the core that is made from the hi-tech material; the outer covering is abrasion and UV resistant braided polyester.

But there are a few issues with them:~

- They don't like being bent through a tight radius. A bowline or any other knot will reduce their strength significantly;

- For the same reason, sheaves must have a diameter of at least eight times the diameter of the line;

- Splicing securely to shackles or other rigging hardware is difficult to achieve, as it's slippery stuff. Best to get these done by a professional rigger...

- As you may have guessed, it's expensive stuff!

My approach on Alacazam is to use Dyneema cored line for all applications that are under load for long periods of time - the jib halyard, staysail halyard, main halyard, spinnaker halyard, kicking strap and checkstays - and pre-stretched polyester braid-on-braid line for all other running rigging applications.

Approximate Line Diameters for Running Rigging

But note the word 'approximate'. More precise diameters can only be determined when additional data regarding line material, sail areas, boat type and safety factors are taken into consideration.

Length of boat

Spinnaker guys

Boom Vang and preventers

Spinnaker sheet

Genoa sheet

Main halyard

Genoa / Jib halyard

Spinnaker halyard

Pole uphaul

Pole downhaul

Reefing pennants

Lengthwise it will of course depend on the layout of the boat, the height of the mast and whether it's a fractional or masthead rig - and if you want to bring everything back to the cockpit...

Read more about Reefing and Sail Handling...

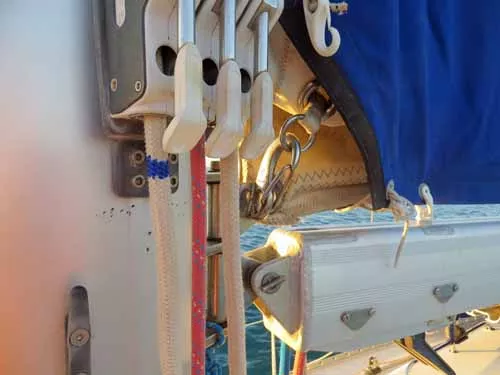

Headsail Roller Reefing Systems Can Jam If Not Set Up Correctly

When headsail roller reefing systems jam there's usually just one reason for it. This is what it is, and here's how to prevent it from happening...

Single Line Reefing; the Simplest Way to Pull a Slab in the Mainsail

Before going to the expense of installing an in-mast or in-boom mainsail roller reefing systems, you should take a look at the simple, dependable and inexpensive single line reefing system

Is Jiffy Reefing the simplest way to reef your boat's mainsail?

Nothing beats the jiffy reefing system for simplicity and reliability. It may have lost some of its popularity due to expensive in mast and in boom reefing systems, but it still works!

Recent Articles

A Hunter Passage 42 for Sale

Jul 16, 24 01:41 PM

The Wauquiez Centurion 40 Sailboat

Jul 15, 24 04:50 AM

The Elan 431 Sailboat

Jul 13, 24 03:03 AM

Here's where to:

- Find Used Sailboats for Sale...

- Find Used Sailing Gear for Sale...

- List your Sailboat for Sale...

- List your Used Sailing Gear...

Our eBooks...

A few of our Most Popular Pages...

Copyright © 2024 Dick McClary Sailboat-Cruising.com

Beginner’s Guide: How To Rig A Sailboat – Step By Step Tutorial

Alex Morgan

Rigging a sailboat is a crucial process that ensures the proper setup and functioning of a sailboat’s various components. Understanding the process and components involved in rigging is essential for any sailor or boat enthusiast. In this article, we will provide a comprehensive guide on how to rig a sailboat.

Introduction to Rigging a Sailboat

Rigging a sailboat refers to the process of setting up the components that enable the sailboat to navigate through the water using wind power. This includes assembling and positioning various parts such as the mast, boom, standing rigging, running rigging, and sails.

Understanding the Components of a Sailboat Rigging

Before diving into the rigging process, it is important to have a good understanding of the key components involved. These components include:

The mast is the tall vertical spar that provides vertical support to the sails and holds them in place.

The boom is the horizontal spar that runs along the bottom edge of the sail and helps control the shape and position of the sail.

- Standing Rigging:

Standing rigging consists of the wires and cables that support and stabilize the mast, keeping it upright.

- Running Rigging:

Running rigging refers to the lines and ropes used to control the sails, such as halyards, sheets, and control lines.

Preparing to Rig a Sailboat

Before rigging a sailboat, there are a few important steps to take. These include:

- Checking the Weather Conditions:

It is crucial to assess the weather conditions before rigging a sailboat. Unfavorable weather, such as high winds or storms, can make rigging unsafe.

- Gathering the Necessary Tools and Equipment:

Make sure to have all the necessary tools and equipment readily available before starting the rigging process. This may include wrenches, hammers, tape, and other common tools.

- Inspecting the Rigging Components:

In the upcoming sections of this article, we will provide a step-by-step guide on how to rig a sailboat, as well as important safety considerations and tips to keep in mind. By following these guidelines, you will be able to rig your sailboat correctly and safely, allowing for a smooth and enjoyable sailing experience.

Key takeaway:

- Rigging a sailboat maximizes efficiency: Proper rigging allows for optimized sailing performance, ensuring the boat moves smoothly through the water.

- Understanding sailboat rigging components: Familiarity with the various parts of a sailboat rigging, such as the mast, boom, and standing and running riggings, is essential for effective rigging setup.

- Importance of safety in sailboat rigging: Ensuring safety is crucial during the rigging process, including wearing a personal flotation device, securing loose ends and lines, and being mindful of overhead power lines.

Get ready to set sail and dive into the fascinating world of sailboat rigging! We’ll embark on a journey to understand the various components that make up a sailboat’s rigging. From the majestic mast to the nimble boom , and the intricate standing rigging to the dynamic running rigging , we’ll explore the crucial elements that ensure smooth sailing. Not forgetting the magnificent sail, which catches the wind and propels us forward. So grab your sea legs and let’s uncover the secrets of sailboat rigging together.

Understanding the mast is crucial when rigging a sailboat. Here are the key components and steps to consider:

1. The mast supports the sails and rigging of the sailboat. It is made of aluminum or carbon fiber .

2. Before stepping the mast , ensure that the area is clear and the boat is stable. Have all necessary tools and equipment ready.

3. Inspect the mast for damage or wear. Check for corrosion , loose fittings , and cracks . Address any issues before proceeding.

4. To step the mast , carefully lift it into an upright position and insert the base into the mast step on the deck of the sailboat.

5. Secure the mast using the appropriate rigging and fasteners . Attach the standing rigging , such as shrouds and stays , to the mast and the boat’s hull .

Fact: The mast of a sailboat is designed to withstand wind resistance and the tension of the rigging for stability and safe sailing.

The boom is an essential part of sailboat rigging. It is a horizontal spar that stretches from the mast to the aft of the boat. Constructed with durable yet lightweight materials like aluminum or carbon fiber, the boom provides crucial support and has control over the shape and position of the sail. It is connected to the mast through a boom gooseneck , allowing it to pivot. One end of the boom is attached to the mainsail, while the other end is equipped with a boom vang or kicker, which manages the tension and angle of the boom. When the sail is raised, the boom is also lifted and positioned horizontally by using the topping lift or lazy jacks.

An incident serves as a warning that emphasizes the significance of properly securing the boom. In strong winds, an improperly fastened boom swung across the deck, resulting in damage to the boat and creating a safety hazard. This incident highlights the importance of correctly installing and securely fastening all rigging components, including the boom, to prevent accidents and damage.

3. Standing Rigging

When rigging a sailboat, the standing rigging plays a vital role in providing stability and support to the mast . It consists of several key components, including the mast itself, along with the shrouds , forestay , backstay , and intermediate shrouds .

The mast, a vertical pole , acts as the primary support structure for the sails and the standing rigging. Connected to the top of the mast are the shrouds , which are cables or wires that extend to the sides of the boat, providing essential lateral support .

The forestay is another vital piece of the standing rigging. It is a cable or wire that runs from the top of the mast to the bow of the boat, ensuring forward support . Similarly, the backstay , also a cable or wire, runs from the mast’s top to the stern of the boat, providing important backward support .

To further enhance the rig’s stability , intermediate shrouds are installed. These additional cables or wires are positioned between the main shrouds, as well as the forestay or backstay. They offer extra support , strengthening the standing rigging system.

Regular inspections of the standing rigging are essential to detect any signs of wear, such as fraying or corrosion . It is crucial to ensure that all connections within the rig are tight and secure, to uphold its integrity. Should any issues be identified, immediate attention must be given to prevent accidents or damage to the boat. Prioritizing safety is of utmost importance when rigging a sailboat, thereby necessitating proper maintenance of the standing rigging. This ensures a safe and enjoyable sailing experience.

Note: <p> tags have been kept intact.

4. Running Rigging

Running Rigging

When rigging a sailboat, the running rigging is essential for controlling the sails and adjusting their position. It is important to consider several aspects when dealing with the running rigging.

1. Choose the right rope: The running rigging typically consists of ropes with varying properties such as strength, stretch, and durability. Weather conditions and sailboat size should be considered when selecting the appropriate rope.

2. Inspect and maintain the running rigging: Regularly check for signs of wear, fraying, or damage. To ensure safety and efficiency, replace worn-out ropes.

3. Learn essential knot tying techniques: Having knowledge of knots like the bowline, cleat hitch, and reef knot is crucial for securing the running rigging and adjusting sails.

4. Understand different controls: The running rigging includes controls such as halyards, sheets, and control lines. Familiarize yourself with their functions and proper usage to effectively control sail position and tension.

5. Practice proper sail trimming: Adjusting the tension of the running rigging significantly affects sailboat performance. Mastering sail trimming techniques will help optimize sail shape and maximize speed.

By considering these factors and mastering running rigging techniques, you can enhance your sailing experience and ensure the safe operation of your sailboat.

The sail is the central component of sailboat rigging as it effectively harnesses the power of the wind to propel the boat.

When considering the sail, there are several key aspects to keep in mind:

– Material: Sails are typically constructed from durable and lightweight materials such as Dacron or polyester. These materials provide strength and resistance to various weather conditions.

– Shape: The shape of the sail plays a critical role in its overall performance. A well-shaped sail should have a smooth and aerodynamic profile, which allows for maximum efficiency in capturing wind power.

– Size: The size of the sail is determined by its sail area, which is measured in square feet or square meters. Larger sails have the ability to generate more power, but they require greater skill and experience to handle effectively.

– Reefing: Reefing is the process of reducing the sail’s size to adapt to strong winds. Sails equipped with reefing points allow sailors to decrease the sail area, providing better control in challenging weather conditions.

– Types: There are various types of sails, each specifically designed for different purposes. Common sail types include mainsails, jibs, genoas, spinnakers, and storm sails. Each type possesses its own unique characteristics and is utilized under specific wind conditions.

Understanding the sail and its characteristics is vital for sailors, as it directly influences the boat’s speed, maneuverability, and overall safety on the water.

Getting ready to rig a sailboat requires careful preparation and attention to detail. In this section, we’ll dive into the essential steps you need to take before setting sail. From checking the weather conditions to gathering the necessary tools and equipment, and inspecting the rigging components, we’ll ensure that you’re fully equipped to navigate the open waters with confidence. So, let’s get started on our journey to successfully rigging a sailboat!

1. Checking the Weather Conditions

Checking the weather conditions is crucial before rigging a sailboat for a safe and enjoyable sailing experience. Monitoring the wind speed is important in order to assess the ideal sailing conditions . By checking the wind speed forecast , you can determine if the wind is strong or light . Strong winds can make sailboat control difficult, while very light winds can result in slow progress.

Another important factor to consider is the wind direction . Assessing the wind direction is crucial for route planning and sail adjustment. Favorable wind direction helps propel the sailboat efficiently, making your sailing experience more enjoyable.

In addition to wind speed and direction, it is also important to consider weather patterns . Keep an eye out for impending storms or heavy rain. It is best to avoid sailing in severe weather conditions that may pose a safety risk. Safety should always be a top priority when venturing out on a sailboat.

Another aspect to consider is visibility . Ensure good visibility by checking for fog, haze, or any other conditions that may hinder navigation. Clear visibility is important for being aware of other boats and potential obstacles that may come your way.

Be aware of the local conditions . Take into account factors such as sea breezes, coastal influences, or tidal currents. These local factors greatly affect sailboat performance and safety. By considering all of these elements, you can have a successful and enjoyable sailing experience.

Here’s a true story to emphasize the importance of checking the weather conditions. One sunny afternoon, a group of friends decided to go sailing. Before heading out, they took the time to check the weather conditions. They noticed that the wind speed was expected to be around 10 knots, which was perfect for their sailboat. The wind direction was coming from the northwest, allowing for a pleasant upwind journey. With clear visibility and no approaching storms, they set out confidently, enjoying a smooth and exhilarating sail. This positive experience was made possible by their careful attention to checking the weather conditions beforehand.

2. Gathering the Necessary Tools and Equipment

To efficiently gather all of the necessary tools and equipment for rigging a sailboat, follow these simple steps:

- First and foremost, carefully inspect your toolbox to ensure that you have all of the basic tools such as wrenches, screwdrivers, and pliers.

- Make sure to check if you have a tape measure or ruler available as they are essential for precise measurements of ropes or cables.

- Don’t forget to include a sharp knife or rope cutter in your arsenal as they will come in handy for cutting ropes or cables to the desired lengths.

- Gather all the required rigging hardware including shackles, pulleys, cleats, and turnbuckles.

- It is always prudent to check for spare ropes or cables in case replacements are needed during the rigging process.

- If needed, consider having a sailing knife or marlinspike tool for splicing ropes or cables.

- For rigging a larger sailboat, it is crucial to have a mast crane or hoist to assist with stepping the mast.

- Ensure that you have a ladder or some other means of reaching higher parts of the sailboat, such as the top of the mast.

Once, during the preparation of rigging my sailboat, I had a moment of realization when I discovered that I had forgotten to bring a screwdriver . This unfortunate predicament occurred while I was in a remote location with no nearby stores. Being resourceful, I improvised by utilizing a multipurpose tool with a small knife blade, which served as a makeshift screwdriver. Although it was not the ideal solution, it allowed me to accomplish the task. Since that incident, I have learned the importance of double-checking my toolbox before commencing any rigging endeavor. This practice ensures that I have all of the necessary tools and equipment, preventing any unexpected surprises along the way.

3. Inspecting the Rigging Components

Inspecting the rigging components is essential for rigging a sailboat safely. Here is a step-by-step guide on inspecting the rigging components:

1. Visually inspect the mast, boom, and standing rigging for damage, such as corrosion, cracks, or loose fittings.

2. Check the tension of the standing rigging using a tension gauge. It should be within the recommended range from the manufacturer.

3. Examine the turnbuckles, clevis pins, and shackles for wear or deformation. Replace any damaged or worn-out hardware.

4. Inspect the running rigging, including halyards and sheets, for fraying, signs of wear, or weak spots. Replace any worn-out lines.

5. Check the sail for tears, wear, or missing hardware such as grommets or luff tape.

6. Pay attention to the connections between the standing rigging and the mast. Ensure secure connections without any loose or missing cotter pins or rigging screws.

7. Inspect all fittings, such as mast steps, spreader brackets, and tangs, to ensure they are securely fastened and in good condition.

8. Conduct a sea trial to assess the rigging’s performance and make necessary adjustments.

Regularly inspecting the rigging components is crucial for maintaining the sailboat’s rigging system’s integrity, ensuring safe sailing conditions, and preventing accidents or failures at sea.

Once, I went sailing on a friend’s boat without inspecting the rigging components beforehand. While at sea, a sudden gust of wind caused one of the shrouds to snap. Fortunately, no one was hurt, but we had to cut the sail loose and carefully return to the marina. This incident taught me the importance of inspecting the rigging components before sailing to avoid unforeseen dangers.

Step-by-Step Guide on How to Rig a Sailboat

Get ready to set sail with our step-by-step guide on rigging a sailboat ! We’ll take you through the process from start to finish, covering everything from stepping the mast to setting up the running rigging . Learn the essential techniques and tips for each sub-section, including attaching the standing rigging and installing the boom and sails . Whether you’re a seasoned sailor or a beginner, this guide will have you ready to navigate the open waters with confidence .

1. Stepping the Mast

To step the mast of a sailboat, follow these steps:

1. Prepare the mast: Position the mast near the base of the boat.

2. Attach the base plate: Securely fasten the base plate to the designated area on the boat.

3. Insert the mast step: Lower the mast step into the base plate and align it with the holes or slots.

4. Secure the mast step: Use fastening screws or bolts to fix the mast step in place.

5. Raise the mast: Lift the mast upright with the help of one or more crew members.

6. Align the mast: Adjust the mast so that it is straight and aligned with the boat’s centerline.

7. Attach the shrouds: Connect the shrouds to the upper section of the mast, ensuring proper tension.

8. Secure the forestay: Attach the forestay to the bow of the boat, ensuring it is securely fastened.

9. Final adjustments: Check the tension of the shrouds and forestay, making any necessary rigging adjustments.

Following these steps ensures that the mast is properly stepped and securely in place, allowing for a safe and efficient rigging process. Always prioritize safety precautions and follow manufacturer guidelines for your specific sailboat model.

2. Attaching the Standing Rigging

To attach the standing rigging on a sailboat, commence by preparing the essential tools and equipment, including wire cutters, crimping tools, and turnbuckles.

Next, carefully inspect the standing rigging components for any indications of wear or damage.

After inspection, fasten the bottom ends of the shrouds and stays to the chainplates on the deck.

Then, securely affix the top ends of the shrouds and stays to the mast using adjustable turnbuckles .

To ensure proper tension, adjust the turnbuckles accordingly until the mast is upright and centered.

Utilize a tension gauge to measure the tension in the standing rigging, aiming for around 15-20% of the breaking strength of the rigging wire.

Double-check all connections and fittings to verify their security and proper tightness.

It is crucial to regularly inspect the standing rigging for any signs of wear or fatigue and make any necessary adjustments or replacements.

By diligently following these steps, you can effectively attach the standing rigging on your sailboat, ensuring its stability and safety while on the water.

3. Installing the Boom and Sails

To successfully complete the installation of the boom and sails on a sailboat, follow these steps:

1. Begin by securely attaching the boom to the mast. Slide it into the gooseneck fitting and ensure it is firmly fastened using a boom vang or another appropriate mechanism.

2. Next, attach the main sail to the boom. Slide the luff of the sail into the mast track and securely fix it in place using sail slides or cars.

3. Connect the mainsheet to the boom. One end should be attached to the boom while the other end is connected to a block or cleat on the boat.

4. Proceed to attach the jib or genoa. Make sure to securely attach the hanks or furler line to the forestay to ensure stability.

5. Connect the jib sheets. One end of each jib sheet should be attached to the clew of the jib or genoa, while the other end is connected to a block or winch on the boat.

6. Before setting sail, it is essential to thoroughly inspect all lines and connections. Ensure that they are properly tensioned and that all connections are securely fastened.

During my own experience of installing the boom and sails on my sailboat, I unexpectedly encountered a strong gust of wind. As a result, the boom began swinging uncontrollably, requiring me to quickly secure it to prevent any damage. This particular incident served as a vital reminder of the significance of properly attaching and securing the boom, as well as the importance of being prepared for unforeseen weather conditions while rigging a sailboat.

4. Setting Up the Running Rigging

Setting up the running rigging on a sailboat involves several important steps. First, attach the halyard securely to the head of the sail. Then, connect the sheets to the clew of the sail. If necessary, make sure to secure the reefing lines . Attach the outhaul line to the clew of the sail and connect the downhaul line to the tack of the sail. It is crucial to ensure that all lines are properly cleated and organized. Take a moment to double-check the tension and alignment of each line. If you are using a roller furling system, carefully wrap the line around the furling drum and securely fasten it. Perform a thorough visual inspection of the running rigging to check for any signs of wear or damage. Properly setting up the running rigging is essential for safe and efficient sailing. It allows for precise control of the sail’s position and shape, ultimately optimizing the boat’s performance on the water.

Safety Considerations and Tips

When it comes to rigging a sailboat, safety should always be our top priority. In this section, we’ll explore essential safety considerations and share some valuable tips to ensure smooth sailing. From the importance of wearing a personal flotation device to securing loose ends and lines, and being cautious around overhead power lines, we’ll equip you with the knowledge and awareness needed for a safe and enjoyable sailing experience. So, let’s set sail and dive into the world of safety on the water!

1. Always Wear a Personal Flotation Device

When rigging a sailboat, it is crucial to prioritize safety and always wear a personal flotation device ( PFD ). Follow these steps to properly use a PFD:

- Select the appropriate Coast Guard-approved PFD that fits your size and weight.

- Put on the PFD correctly by placing your arms through the armholes and securing all the straps for a snug fit .

- Adjust the PFD for comfort , ensuring it is neither too tight nor too loose, allowing freedom of movement and adequate buoyancy .

- Regularly inspect the PFD for any signs of wear or damage, such as tears or broken straps, and replace any damaged PFDs immediately .

- Always wear your PFD when on or near the water, even if you are a strong swimmer .

By always wearing a personal flotation device and following these steps, you will ensure your safety and reduce the risk of accidents while rigging a sailboat. Remember, prioritize safety when enjoying water activities.

2. Secure Loose Ends and Lines

Inspect lines and ropes for frayed or damaged areas. Secure loose ends and lines with knots or appropriate cleats or clamps. Ensure all lines are properly tensioned to prevent loosening during sailing. Double-check all connections and attachments for security. Use additional safety measures like extra knots or stopper knots to prevent line slippage.

To ensure a safe sailing experience , it is crucial to secure loose ends and lines properly . Neglecting this important step can lead to accidents or damage to the sailboat. By inspecting, securing, and tensioning lines , you can have peace of mind knowing that everything is in place. Replace or repair any compromised lines or ropes promptly. Securing loose ends and lines allows for worry-free sailing trips .

3. Be Mindful of Overhead Power Lines

When rigging a sailboat, it is crucial to be mindful of overhead power lines for safety. It is important to survey the area for power lines before rigging the sailboat. Maintain a safe distance of at least 10 feet from power lines. It is crucial to avoid hoisting tall masts or long antenna systems near power lines to prevent contact. Lower the mast and tall structures when passing under a power line to minimize the risk of contact. It is also essential to be cautious in areas where power lines run over the water and steer clear to prevent accidents.

A true story emphasizes the importance of being mindful of overhead power lines. In this case, a group of sailors disregarded safety precautions and their sailboat’s mast made contact with a low-hanging power line, resulting in a dangerous electrical shock. Fortunately, no serious injuries occurred, but it serves as a stark reminder of the need to be aware of power lines while rigging a sailboat.

Some Facts About How To Rig A Sailboat:

- ✅ Small sailboat rigging projects can improve sailing performance and save money. (Source: stingysailor.com)

- ✅ Rigging guides are available for small sailboats, providing instructions and tips for rigging. (Source: westcoastsailing.net)

- ✅ Running rigging includes lines used to control and trim the sails, such as halyards and sheets. (Source: sailingellidah.com)

- ✅ Hardware used in sailboat rigging includes winches, blocks, and furling systems. (Source: sailingellidah.com)

- ✅ A step-by-step guide can help beginners rig a small sailboat for sailing. (Source: tripsavvy.com)

Frequently Asked Questions

1. how do i rig a small sailboat.

To rig a small sailboat, follow these steps: – Install or check the rudder, ensuring it is firmly attached. – Attach or check the tiller, the long steering arm mounted to the rudder. – Attach the jib halyard by connecting the halyard shackle to the head of the sail and the grommet in the tack to the bottom of the forestay. – Hank on the jib by attaching the hanks of the sail to the forestay one at a time. – Run the jib sheets by tying or shackling them to the clew of the sail and running them back to the cockpit. – Attach the mainsail by spreading it out and attaching the halyard shackle to the head of the sail. – Secure the tack, clew, and foot of the mainsail to the boom using various lines and mechanisms. – Insert the mainsail slugs into the mast groove, gradually raising the mainsail as the slugs are inserted. – Cleat the main halyard and lower the centerboard into the water. – Raise the jib by pulling down on the jib halyard and cleating it on the other side of the mast. – Tighten the mainsheet and one jibsheet to adjust the sails and start moving forward.

2. What are the different types of sailboat rigs?

Sailboat rigs can be classified into three main types: – Sloop rig: This rig has a single mast with a mainsail and a headsail, typically a jib or genoa. – Cutter rig: This rig has two headsails, a smaller jib or staysail closer to the mast, and a larger headsail, usually a genoa, forward of it, alongside a mainsail. – Ketch rig: This rig has two masts, with the main mast taller than the mizzen mast. It usually has a mainsail, headsail, and a mizzen sail. Each rig has distinct characteristics and is suitable for different sailing conditions and preferences.

3. What are the essential parts of a sailboat?

The essential parts of a sailboat include: – Mast: The tall vertical spar that supports the sails. – Boom: The horizontal spar connected to the mast, which extends outward and supports the foot of the mainsail. – Rudder: The underwater appendage that steers the boat. – Centerboard or keel: A retractable or fixed fin-like structure that provides stability and prevents sideways drift. – Sails: The fabric structures that capture the wind’s energy to propel the boat. – Running rigging: The lines or ropes used to control the sails and sailing equipment. – Standing rigging: The wires and cables that support the mast and reinforce the spars. These are the basic components necessary for the functioning of a sailboat.

4. What is a spinnaker halyard?

A spinnaker halyard is a line used to hoist and control a spinnaker sail. The spinnaker is a large, lightweight sail that is used for downwind sailing or reaching in moderate to strong winds. The halyard attaches to the head of the spinnaker and is used to raise it to the top of the mast. Once hoisted, the spinnaker halyard can be adjusted to control the tension and shape of the sail.

5. Why is it important to maintain and replace worn running rigging?

It is important to maintain and replace worn running rigging for several reasons: – Safety: Worn or damaged rigging can compromise the integrity and stability of the boat, posing a safety risk to both crew and vessel. – Performance: Worn rigging can affect the efficiency and performance of the sails, diminishing the boat’s speed and maneuverability. – Reliability: Aging or worn rigging is more prone to failure, which can lead to unexpected problems and breakdowns. Regular inspection and replacement of worn running rigging is essential to ensure the safe and efficient operation of a sailboat.

6. Where can I find sailboat rigging books or guides?

There are several sources where you can find sailboat rigging books or guides: – Online: Websites such as West Coast Sailing and Stingy Sailor offer downloadable rigging guides for different sailboat models. – Bookstores: Many bookstores carry a wide selection of boating and sailing books, including those specifically focused on sailboat rigging. – Sailing schools and clubs: Local sailing schools or yacht clubs often have resources available for learning about sailboat rigging. – Manufacturers: Some sailboat manufacturers, like Hobie Cat and RS Sailing, provide rigging guides for their specific sailboat models. Consulting these resources can provide valuable information and instructions for rigging your sailboat properly.

About the author

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Latest posts

The history of sailing – from ancient times to modern adventures

History of Sailing Sailing is a time-honored tradition that has evolved over millennia, from its humble beginnings as a means of transportation to a beloved modern-day recreational activity. The history of sailing is a fascinating journey that spans cultures and centuries, rich in innovation and adventure. In this article, we’ll explore the remarkable evolution of…

Sailing Solo: Adventures and Challenges of Single-Handed Sailing

Solo Sailing Sailing has always been a pursuit of freedom, adventure, and self-discovery. While sailing with a crew is a fantastic experience, there’s a unique allure to sailing solo – just you, the wind, and the open sea. Single-handed sailing, as it’s often called, is a journey of self-reliance, resilience, and the ultimate test of…

Sustainable Sailing: Eco-Friendly Practices on the boat

Eco Friendly Sailing Sailing is an exhilarating and timeless way to explore the beauty of the open water, but it’s important to remember that our oceans and environment need our protection. Sustainable sailing, which involves eco-friendly practices and mindful decision-making, allows sailors to enjoy their adventures while minimizing their impact on the environment. In this…

- AROUND THE SAILING WORLD

- BOAT OF THE YEAR

- Email Newsletters

- America’s Cup

- St. Petersburg

- Caribbean Championship

- Boating Safety

Simple Ways to Optimize Running Rigging

- By Erik Shampain

- December 6, 2022

It’s easy to underestimate the benefits of good running rigging. There are many rope products on the market, and there is a time and a place for most of them. Let’s take a look at lines that need the most attention and why, as well as basic rules for using low-stretch line, using lightweight or tapered line where most beneficial and using rope that is easy to work with.

Let’s start up front with the headsail halyard. Luff tension greatly affects shape and thus performance of the jib or genoa, so having a halyard that is as low-stretch as possible is paramount. Saving a little weight aloft is also key, so find a lightweight rope as well. It’s a little against the norm, but for club racing boats that aren’t tapering their halyards, I really like some of the Vectran-cored ropes. Products like Samson’s Validator and New England Ropes V-100 are easy on the hands and easy to splice. For a little more grand-prixed tapered halyard, talk to our local rigger about using a DUX core, or other heat-set Dyneema, with a Technora-based cover. Lately, I’ve been using a lot of Marlow’s D12 MAX 78 and 99. Tapering the halyard saves weight aloft as well. I like soft shackles for jib halyards. There, weight savings aloft generally outweighs the little extra time a bowman needs to attach the sail. This is especially true in sprit boats where the jib is rarely removed from the headstay.

Pro Tip: When not racing, use a halyard leader to pull the halyards to the top of the mast, getting the tapered section out of the sun. For extra protection, put all the halyard tails into an old duffle bag at the base of the mast when not in use.

For jib sheets, I follow the same low-stretch rule as the jib halyard. I don’t want the jib sheet to stretch at all when a puff hits. On boats with overlapping genoas, I don’t generally recommend tapering the line because by the time the genoa is trimmed all the way in, the clew is really close to the block. On boats with non-overlapping jibs, tapering is an easy way to save a little weigh. Plus, the smaller core size runs through across the boat more easily in tacks. I’ve been using soft shackles on the jib or genoa sheets for a while now, mostly because they don’t beat the mast up during tacks. There also a bit “softer” when they hit you.

What about jib lead adjusters? There are a couple of approaches here. Some believe a little stretch is okay, as it allows the lead to rock aft a couple of millimeters in puffs, which twists the top of the jib off slightly. This can be fast as it helps the boat transition through puffs and lulls. I am a fan of this as long as it isn’t too stretchy. I use low-stretch Dyneema for the gross part of the purchase and then a friendlier-on-the-hands rope for the fine tune side, the part that is being handled. Samson Warpspeed or New England Enduro Braid work well.

Spinnaker sheets are a fun one. They should be relatively low-stretch but not necessarily the lowest stretch. I’ve found that near-zero stretch lines can wreak havoc on people and hardware when flogging or when the chute is collapsing. They have to be easy on the hands, as they are the most moved sheets on the boat, and they should be tapered as far as you can get away with. Tapering saves weigh, which is very important in keeping the spinnaker clew lifting up, especially in light air when sails want to droop. Again, Samson Warpseed and New England Enduro braid are good. For boats with grinders or even small boats with no winches, a cover that is a little grippier or stronger is good. Most Technora-based covers work well for this purpose.

Pro Tip No. 2: On boats with asymmetric spinnakers I like to connect the ‘Y’ sheet with a soft shackle that also goes to the spinnaker. This saves weight. I sew a Velcro strip around one part of the shackle (see picture) so that the soft shackle stays with the ‘Y’ sheet when open. This is beneficial when you have to quickly disconnect or re-run a sheet, replace one sheet, or even quickly replace a soft shackle. On most boats I will keep one spare spinnaker sheet with soft shackle down below as a spare side, changing sheet, or code zero sheet. On boats with a symmetric spinnaker, we’ll splice the spinnaker sheet to the afterguy shackle to save weight in the clew.

The spinnaker halyard has a couple of more options. For halyards supporting code zeros, zero stretch is important. The same principals we used when talking about the jib halyard apply here. For boats without code zeros, I like a little softer halyard with a touch of give. Those tend to run though sheaves better without kinking. Enduro and Warpseed are good for these applications. Most bowmen prefer a shackle that is quick and easy to open. Since a happy bowman is a good thing, I will generally use an appropriately sized Tylaska shackle or dogbone style shackle for those halyards

For symmetric spinnaker boats, the afterguy must be very low stretch line. I go back to products like covered Vectran for club-level sheets. I also find that afterguys generally last longer if I don’t taper them. When the pole is squared back, the afterguys often run pretty hard across the lifelines, producing a fair amount of chafe. Covered lines help minimize that.

For tack lines on asymmetric boats, I like matching spinnaker halyard material on club-level boats and using low-stretch heat-set Dyneema cores with a chafe resistant cover for grand prix and sportboats.

Like the headsail halyard, a near-zero stretch main halyard is also important. For me the same line applications apply. Keep the mainsail head at full hoist at all costs. I will often match the material I use for main and jib halyards.

It is most important that the main sheet sit in the winch jaws well and tail perfectly. This is a strict combination of sizing and pliability. I’ve found that the New England Ropes Enduro braid and the Samson Warpspeed II work well for club-level boats with and without winches. For a slightly longer lasting product with some chafe resistance, try any manufacturer’s Technora-based covered line.

The most under-appreciated and least thought about rope on a boat always seems to be the outhaul. The last thing you want when the wind comes up is for your mainsail to get fuller. Spend some time here and use very low-stretch rope. Most heat-set Dyneemas will work great for the gross tune side of the purchase.

Pro Tip No. 3: Minimizing the last purchase of an outhaul greatly increases the ease with which it can be pulled on or eased out. For example, you could have a 6-to-1 to one pulling a 2-to-1, pulling a 2-to-1 and then to the sail for a 24-to-1. Or, better yet, you could have a 4-to-1 pulling a 3-to-1, pulling a 2-to-1 for a 24-to-1 as well. The latter example will work better. Trust me. I’m a doctor . . . sort of. We built an outhaul like this on a SC50. I can pull it on upwind in heavy air with little problem. On the flip side, in light air downwind, it eases just as well. In fact, if memory serves me right, we did a 3-to-1 in the end rather than the 4-to-1 for a total of 18-to-1 and it worked well.

Runners and backstays should have extremely low stretch. A pumping mast and sagging forestay in breeze isn’t fast. Runner tails, like the mainsheet, should perfectly fit the winch and tail easily without kinking.

With so many options readily on the market now, it can be very confusing. I always recommend contacting your local rigger if you have any questions at all about what rope is right for you. They’ll get you pulling in the right direction.

- More: cordage , running rigging , sailboat gear

Reproofing May Be Required

Wingfoiling Gear: A Beginner’s Guide

Suiting Up with Gill’s ZenTherm 2.0

Gill Verso Lite Smock Keeps it Simple

Black Foils Pad Season Lead with SailGP New York Win

Widnall Prize Announced for Helly Hansen Sailing World Regatta at Marblehead Race Week

Sagamore Ridealong in Chicago

- Digital Edition

- Customer Service

- Privacy Policy

- Cruising World

- Sailing World

- Salt Water Sportsman

- Sport Fishing

- Wakeboarding

Running Rigging on a Sailboat: Essential Components and Maintenance Tips

by Emma Sullivan | Aug 8, 2023 | Sailboat Maintenance

Short answer running rigging on a sailboat:

Running rigging refers to the ropes and lines used for controlling the sails and other movable parts on a sailboat. It includes halyards, sheets, braces, and control lines. Properly rigged running rigging is essential for efficient sail handling and maneuvering of the boat.

Understanding Running Rigging on a Sailboat: How to Get Started

Title: Deciphering the Intricacies of Running Rigging on a Sailboat: An Enlightened Journey Begins!

Introduction: Ah, the allure of sailing! Picture yourself gracefully gliding across sun-kissed waters, propelled solely by the power of the wind . If you’re new to this mesmerizing world, it’s crucial to understand every aspect – including running rigging. Fear not, fellow adventurer! This comprehensive guide will unravel the mysteries surrounding running rigging and equip you with valuable knowledge to embark upon your own nautical odyssey.

1. The Foundations: What is Running Rigging? Running rigging encompasses all the ropes and lines aboard a sailboat that are used to control sails and their systems. Think of it as a symphony conductor guiding each instrument precisely when they are needed. Understanding its components requires delving into various key elements.

2. The Halyards: Hoisting Your Sails with Elegance Halyards form an integral part of running rigging by facilitating the raising and lowering of sails effortlessly. These vital maneuvering aids connect from the masthead down to specific positions where they secure each sail precisely at one end while granting sailors control at their opposite extremity.

3. Sheets & Controls: Directing Your Power Source Next up in our deconstruction are sheets and controls – essential components for controlling sails’ angles based on wind direction. By cunningly pulling or easing these lines, you can swiftly adjust your sails’ positioning according to weather shifts, resulting in optimal performance .

4. Cleats & Winches: From Taming Lines to Seizing Moments Even Hercules would yield to cleats and winches when taming robust ropes! Cleats serve as steadfast anchors onto which lines can be temporarily secured, providing necessary stability during navigation’s turbulent moments. Winches, on the other hand, offer mechanical assistance by efficiently winding or unwinding lines using a drum mechanism – a sailor’s secret weapon for effortlessly controlling lines under high tension.

5. Blocks & Pulleys: The Silent Workhorses Up Above Blocks and pulleys, hidden amongst the chaos of running rigging, serve as silent heroes deserving recognition. These nifty devices allow lines to redirect their path efficiently, minimizing friction while maximizing mechanical advantage. Imagine them as your trusty allies, ensuring smooth adjustments without burdening you with unnecessary strain.

6. Mainsail Furling Systems: Embracing Elegance in Simplicity To master running rigging effectively, one must grasp the concept of mainsail furling systems. These mechanisms enable swift and straightforward reefing or unfurling of the mainsail using dedicated ropes or electrically-powered systems. By harnessing this technology correctly, you’ll unlock newfound ease in sailing endeavors.

Conclusion: Congratulations! You’ve delved into the intricate world of running rigging on a sailboat and emerged more enlightened than ever before. As you embark upon your maritime journey armed with this invaluable knowledge, remember that practice leads to mastery. Understanding how these distinct elements harmonize will transform you into a maestro, skillfully orchestrating every aspect of your sailing adventure with grace and finesse. Bon voyage!

A Step-by-Step Guide to Setting Up Running Rigging on a Sailboat

Title: Sailing with Confidence: A Masterclass on Setting Up Running Rigging

Introduction:

Embarking on the open sea , feeling the wind against your face as you glide through the water, there’s no greater thrill than sailing. However, to truly harness the power of the wind and have a seamless experience, it is essential to understand how to set up your running rigging. In this comprehensive guide, we will take you through each step of this crucial process, equipping you with the knowledge and confidence necessary for smooth sailing adventures.

1. Assessing Your Needs: The Foundation for Success

Before diving into the nitty-gritty details of setting up your running rigging, it’s important to assess your specific needs according to your sailboat’s design and intended use. Factors such as boat size, mast height, and sail types play a significant role in determining which rigging configurations will work best for you.

2. Selecting Materials: Optimal Performance, Durability & Safety

Choosing suitable materials for running rigging is paramount to ensure reliable performance while maintaining the safety of both crew and vessel. From strong yet lightweight synthetic fibers like Dyneema or Spectra to traditional options such as polyester or nylon, understanding their properties and appropriate applications is essential in making informed decisions.

3. Understanding Key Terminology: Speaking Sailors’ Language

Like any specialized field, sailing has its own set of terminology that can feel overwhelming at first. Fear not! We’ll guide you through key terms such as halyards (hoisting lines), sheets (lines controlling sails), reefing lines (to reduce sail area), allowing you to converse confidently with fellow sailors.

4. Anchoring Your Mast: Secure Your Foundation

The process begins by firmly anchoring your mast at its base using a fitting called a mast step or deck collar. This immovable foundation provides stability throughout various sailing conditions while reducing unnecessary strain on all related rigging components .

5. Hoisting the Sails: Halyards & Their Art

To set sail, a crucial step involves hoisting your sails with precision. Correctly attaching halyards to the designated points on the mast and sail, while ensuring proper tension and alignment, will enable you to control raising, lowering, and reefing the sails with ease—an art form in itself.

6. Harnessing the Wind’s Power: Sheets & Trimming

Once your sails are aloft, skillful manipulation of sheets becomes paramount. Understanding how to trim them properly allows you to harness the wind’s power effectively while achieving maximum speed and maneuverability—a true dance between sailor and nature.

7. Streamlining Movement: Fairleads & Blocks

Efficiency is key when it comes to running rigging. By employing fairleads (pulleys) strategically placed around your vessel and appropriately using blocks (pulley combinations), you can minimize friction within your system, allowing for fluid movement with less effort during sail adjustments.

8. Reducing Sail Area: Reefing Lines at the Ready

As conditions change or storms approach, being able to reduce sail area swiftly is essential for safety purposes. Learning how to utilize reefing lines effectively enables you to adapt your sails according to environmental demands without sacrificing control or stability.

9. Fine-Tuning Your Set-Up: Tension & Balance

The final touch lies in adjusting tension throughout your running rigging system to achieve optimal balance and performance. Maintaining proper tension prevents undesirable effects like excessive wrinkles on sails or slack lines that compromise efficiency—fine-tuning that separates amateurs from seasoned sailors.

10. Everyday Maintenance: Caring For Your Rigging

Just as a well-maintained engine ensures peak performance, regularly caring for your running rigging also guarantees smooth operation over time. Simple tasks such as rinsing off saltwater residue or inspecting for wear and tear go a long way in prolonging the life of your rigging and ensuring a safe voyage.

Conclusion:

With this step-by-step guide, you are now equipped with the knowledge needed to set up running rigging on your sailboat like a seasoned sailor. By understanding the essential components, choosing suitable materials, and mastering the techniques necessary for trimming and maintenance, you’ll confidently navigate the open seas while experiencing the true joy of sailing . Bon voyage!

Frequently Asked Questions about Running Rigging on a Sailboat Demystified

Welcome to the world of sailing! If you’re a beginner or even if you’ve been sailing for a while, running rigging can often seem like a complex and confusing topic. But fear not! In this blog post, we are here to demystify all your frequently asked questions about running rigging on a sailboat.

Q: What is running rigging? A: Running rigging refers to all the lines and ropes that control and adjust the sails on a sailboat. It includes halyards, sheets, reefing lines, downhauls, and any other line used to set or trim sails .

Q: Why is running rigging important? A: Running rigging plays a crucial role in controlling the shape and position of the sails, allowing the boat to harness wind power efficiently . Properly adjusted running rigging enables better sail control, improved performance, and increased safety on board.

Q: How many types of running rigging are there? A: There are several types of running rigging found on most sailboats. Some common ones are halyards (used to lift or lower the sails), sheets (used to control the tension and angle of the sails), outhauls (used to adjust the foot of the mainsail), furling lines (used for rolling up or unfurling headsails), and vang systems (used for controlling boom height).

Q: What materials are used in running rigging? A: Traditionally, natural fibers like hemp or manila were used for ropes. However, modern sailboats mostly use synthetic fibers such as polyester or Dyneema due to their durability, low stretching properties, and resistance to UV degradation.

Q: How do I choose the right running rigging for my boat? A: The choice of running rigging depends on various factors such as boat size/type, sailing conditions, intended use, personal preference, and budget. It’s always advisable to consult with a reputable rigging professional who can assess your specific requirements and recommend the appropriate type and diameter of ropes for your boat .

Q: How often should I replace my running rigging? A: The lifespan of running rigging depends on various factors including usage, exposure to sunlight, and regular maintenance. As a general rule of thumb, inspect your running rigging regularly for signs of wear and tear. If you notice any fraying, excessive stretching, or damage, it’s essential to replace the affected lines promptly.

Q: Can I maintain my own running rigging? A: Yes! Regular maintenance is key to prolonging the life of your running rigging. Simple tasks like washing with fresh water after use, removing dirt or salt residue, and storing the lines properly can significantly extend their lifespan. However, if you’re unsure about any specific maintenance tasks or need assistance with more complex issues, it’s best to seek advice from a professional rigger.

Q: Are there any advanced techniques related to running rigging? A: Absolutely! Advanced sailing techniques often involve various adjustments using different lines simultaneously. For example, using barberhaulers to control genoa sheeting angles or implementing cunningham systems for mainsail shape adjustments. These techniques require practice and knowledge but can greatly enhance sail efficiency and boat performance.

Now that we’ve demystified some frequently asked questions about running rigging on a sailboat, we hope you feel more confident in understanding this vital aspect of sailing. Remember that every boat is unique, so investing time in learning about and maintaining your specific running rigging system will undoubtedly pay off in smoother sailing experiences ahead!

Choosing the Right Materials for Your Sailboat’s Running Rigging

When it comes to your sailboat’s running rigging, choosing the right materials can make all the difference in ensuring optimal performance and longevity. But with a plethora of options available, it can be a daunting task. Fear not, for we are here to guide you through this decision-making process, providing you with a detailed professional, witty and clever explanation.

First and foremost, let’s clarify what we mean by “running rigging.” In sailing terms, this refers to all the lines (ropes) used to control the sails and their adjustments while underway. These lines include halyards (used for raising and lowering the sails), sheets (controls the angle and trim of the sails), and various other control lines like reefing lines or vang lines. Each requires specific characteristics based on its purpose.

When considering materials for running rigging, durability is paramount. You want something that can withstand constant exposure to UV rays, saltwater, friction wear, and general wear and tear. One material that stands out in terms of resilience is Dyneema®. This high-performance synthetic fiber boasts an incredible strength-to-weight ratio similar to steel but without the weight or corrosion concerns. Paired with excellent resistance to UV degradation and abrasion resistance properties, Dyneema® offers a long-lasting solution for your running rigging needs.

But hold on! While Dyneema® may seem like an obvious choice, there are other factors to consider as well. For instance, ease of handling plays a significant role in determining which material is right for you. Some sailors prefer traditional materials like polyester or nylon due to their familiar feel and ease of tying knots. However, these materials tend to stretch more under load compared to Dyneema®, which can affect sail shape and overall performance .

To address this issue without compromising on durability or ease of handling completely, manufacturers have developed hybrid rope constructions where different fibers are combined strategically within a single line. For example, a Dyneema® core can be paired with a polyester or Technora cover, harnessing the best of both worlds. This combination provides the strength and low stretch characteristics of Dyneema® while maintaining that traditional feel when handling.

Now, let’s sprinkle in some wit and cleverness as we delve into the importance of reliability. When out on the open seas, you don’t want to be caught off guard by a line failure because you chose an unreliable material. Imagine your excitement as the wind picks up, preparing for an exhilarating sail, only to have your sailing dreams dashed due to a snapped halyard! Trust me; it’s not an experience you’ll find amusing, nor will your crew appreciate your comedic skills at such moments. So, don’t skimp on quality.

To ensure reliability and avoid any unplanned comedy acts on board, investing in well-respected brands known for their commitment to excellence is key. Reputable manufacturers like New England Ropes or Marlow Ropes are popular choices among sailors worldwide. Their rigorous testing processes and innovative designs guarantee performance reliability no matter what Mother Nature throws your way.

We hope this detailed professional, witty and clever explanation has shed some light on choosing the right materials for your sailboat’s running rigging. Remember to consider durability, ease of handling, and reliability when making your decision. And if you’re still unsure or need further assistance—don’t hesitate to reach out to fellow sailors or consult with professionals who can offer personalized advice tailored to your unique sailing style. Happy rigging!

Essential Tips for Properly Maintaining and Inspecting Running Rigging on a Sailboat

As any experienced sailor knows, properly maintaining and inspecting the running rigging on a sailboat is crucial for optimal performance and safety on the water. The running rigging refers to all the lines or ropes that control the sails, such as halyards, sheets, and control lines. Neglecting this essential aspect of sailboat ownership can lead to inefficiencies in sailing, potential equipment failures, or even dangerous situations while out at sea. So, whether you’re a seasoned sailor or just starting out, here are some essential tips to keep your running rigging in top shape.

1. Regular Inspection: The first step in proper maintenance is conducting regular inspections of your running rigging. Look for signs of wear and tear such as fraying, chafing, or any weakening spots in the ropes. Pay close attention to areas where lines are frequently under tension or make contact with other hardware, as these are typically high-stress areas prone to damage.

2. Cleaning: It’s vital to keep your running rigging clean and free from contaminants like dirt, saltwater residue, or mildew buildup that can affect their performance over time. Use a mild soap and water solution along with a soft brush to scrub away any grime.

3. Protect from UV Damage: Exposure to sunlight can accelerate the wear and degradation of your ropes due to UV radiation. Consider covering them with protective sleeves or using UV-resistant coatings specifically designed for sailing applications.

4. Lubrication: Keeping your running rigging well-lubricated ensures smooth operation and prolongs their lifespan. Apply a suitable marine-grade lubricant to reduce friction between moving parts like pulleys and cleats but be cautious not to apply excessive amounts that could attract dirt or create messy situations.

5. Check Fittings & Hardware: A comprehensive inspection should include examining all fittings and hardware associated with your running rigging – blocks, shackles, cam cleats – to ensure they are in proper working order. Tighten any loose fittings and replace any worn or damaged hardware promptly.

6. Replace Worn-out Lines: As with anything made of rope, running rigging will eventually reach the end of its serviceable life. Don’t wait for lines to fail before replacing them. Look out for signs like significant diameter reduction, loss of flexibility, or extensive wear and tear. Replacing worn-out lines early can save you from potential accidents or interruptions during your sailing adventures .

7. Proper Storage: When not in use, it’s essential to store your running rigging properly to avoid unnecessary damage or deterioration. Coil the lines neatly and hang them in a cool, dry place where they are protected from direct sunlight and extreme temperatures.

By following these essential tips for maintaining and inspecting your sailboat’s running rigging, you’ll be able to enjoy smooth sailing while ensuring your safety out on the water. Regular inspections, cleaning, UV protection, lubrication, checking fittings and hardware, timely replacements when necessary, and proper storage – all these factors contribute to keeping your running rigging in top shape for optimal performance on every voyage.

Remember that sailboat ownership is an ongoing learning process – stay curious and educate yourself further through reputable sources such as books or online forums dedicated to sailing techniques and equipment maintenance. Happy sailing!

Upgrading Your Sailboat’s Running Rigging: What You Need to Know

When it comes to sailing, few things are as important as the running rigging of your sailboat. From controlling your sails to maneuvering through tricky waters, the quality and functionality of your running rigging can make all the difference in your sailing experience. In this blog post, we will explore everything you need to know about upgrading your sailboat’s running rigging.

Why Upgrade?

Before diving into the details of upgrading your running rigging, let’s discuss why it is necessary in the first place. Over time, the wear and tear on a sailboat’s running rigging can lead to compromised performance and safety concerns. As such, periodic upgrades become essential to ensure optimal functionality and reliability on the water .

Choosing Material

One of the most critical decisions when upgrading your running rigging is choosing the right material. Traditionally, sailboats have used materials like polyester or Dacron for their ropes. While these options are cost-effective and suitable for casual sailors, advanced materials like Dyneema or Spectra offer superior strength-to-weight ratio and lower stretch capabilities.

Furthermore, these modern fibers provide exceptional durability against UV degradation and abrasion resistance – perfect for longer ocean passages or demanding racing environments. Investing in high-quality lines may be more expensive upfront but pays off by enhancing both safety and performance while extending the overall lifespan of your rigging system.

Understanding Line Construction

Now that we’ve covered material options let’s move onto line construction. When choosing new lines for your running rigging upgrade, understanding their construction plays a vital role in achieving desired results.

Double braid construction is one popular option known for its balance between stretch resistance and knotability. It consists of a core surrounded by a braided outer cover – providing both strength and flexibility when handling heavier loads.

Alternatively, single braid construction offers improved flexibility by using only one continuous rope with a braided or twisted cover. This design is perfect for smaller sailboats, giving you lighter and more manageable lines while sacrificing some load-bearing capacity.

Finding the Perfect Fit

Upgrading your running rigging goes beyond simply replacing old lines with new ones; finding the perfect fit for your specific needs is crucial. Before making any purchases, take time to assess how you use your sailboat and what characteristics matter most to you.

Consider factors like line diameter, breaking strength, elongation under load, and grip comfort when evaluating potential options. While durability is essential, striking the right balance between strength and weight can significantly enhance your sailing experience .

Installation 101

Now that you’ve selected the ideal running rigging components let’s talk about installation. Proper installation ensures optimal functionality and reduces potential snags or accidents on the water.

Start by studying your sailboat’s existing rigging setup and create a detailed plan to avoid confusion during installation. If possible, consult with experts or refer to manufacturer guidelines for best practices.

Lastly, pay careful attention to tensioning techniques when installing your new lines – correct tension prevents slack that may hinder overall performance during navigation.

Maintaining Your Upgrade

Once completed, maintaining your newly upgraded running rigging becomes an essential part of owning a sailboat. Regular inspection of ropes for wear and tear is necessary since even high-quality materials require upkeep.

Additionally, proper storage away from UV rays and harsh weather conditions can further extend the life of your upgraded running rigging. By following maintenance guidelines provided by manufacturers and incorporating routine checks in pre-sail preparations, you can ensure continued reliability throughout every journey.

Upgrading your sailboat’s running rigging is a worthwhile investment that guarantees enhanced safety and performance while providing endless possibilities on the water. Choosing suitable materials based on usage patterns, understanding line construction principles, finding the perfect fit for specific needs, meticulous installation processes, and regular maintenance are key elements in achieving desired results.

So, take the plunge and upgrade your running rigging today – it’s time to elevate your sailing experience to new heights!

Recent Posts

- Sailboat Gear and Equipment

- Sailboat Lifestyle

- Sailboat Maintenance

- Sailboat Racing

- Sailboat Tips and Tricks

- Sailboat Types

- Sailing Adventures

- Sailing Destinations

- Sailing Safety

- Sailing Techniques

- Anchoring & Mooring

- Boat Anatomy

- Boat Culture

- Boat Equipment

- Boat Safety

- Sailing Techniques

Sailboat Running Rigging Explained

Running rigging refers to the essential lines, ropes, and hardware responsible for controlling, adjusting, and managing the sails on a sailboat. They directly impact a sailboat’s performance, maneuverability, and overall safety.

As a result, understanding different running rigging components and their functions can help us optimize our boat’s performance and make informed decisions in various sailing situations. This comprehensive guide delves deep into the world of rigging by examining its essential components and various aspects, including materials, maintenance, advancements, troubleshooting, knots, and splices.

Key Takeaways

- Running rigging consists of movable components like halyards, sheets, and control lines that control, adjust, and handle the sails.

- Synthetic materials like Dyneema, Spectra, and Vectran have revolutionized running rigging due to their superior strength-to-weight ratio, low stretch and abrasion resistance, and increased lifespan.

- Troubleshooting common running rigging problems involves untangling or untwisting lines, resolving jammed or stuck hardware, and ensuring lines hold tension correctly.

- Knowing how to tie knots and splice lines is crucial in connecting running rigging components, securing lines, and adjusting sails.

- To achieve the best performance, the boat's rigging should be tailored to specific sailing needs, either racing or cruising.

- Different sailboat types and configurations require specific running rigging setups.

Difference between running and standing rigging

Before diving into the components, it’s essential to understand the difference between standing and running rigging. Standing rigging consists of the fixed lines, cables, and rods responsible for supporting a sailboat’s mast(s) and maintaining stability. Examples of standing rigging include shrouds, stays, and spreaders.

Running rigging, on the other hand, comprises the movable components needed to control, adjust, and handle the sails. These elements allow us to raise, lower, and trim the sails according to wind conditions and the boat’s course. Understanding the distinction between the two types of rigging is vital in operating a sailboat safely and efficiently.

Components of Running Rigging on a Sailboat

Responsible for raising, lowering, and holding sails in their deployed position. The primary types include the main halyard (for the mainsail), jib halyard (for jibs or genoas), and spinnaker halyard (for spinnakers). They typically run from the head of the sail down to mast-mounted winches or lead back to the cockpit for easy adjustment.

Control the angle of a sail relative to the wind. They connect the clew to the deck or another part of the rigging (e.g., tack), allowing adjustments and fine-tuning of sail trim . The two main types of sheets are mainsheets (for mainsails) and jib/genoa sheets (for headsails).

Control Lines

Essential for adjusting the tension and shape of sails. Examples include outhauls (for foot tension), cunninghams (for luff tension), and reef lines (for reducing the area under high wind conditions). Proper use of these lines allows sailors to optimize sail shape, improve efficiency, and manage their boats in various wind conditions.

Maintenance and Care

Regular inspection.

Routine inspection of your rigging is essential to identify wear, damage, or issues before they escalate into severe problems. Conduct a thorough examination at least once a season or more frequently if you sail extensively. When inspecting, check for signs of chafe, abrasion, corrosion, frayed, or damaged rope sections. Address these issues promptly to prevent further complications.

Cleaning and maintaining

Proper cleaning and maintenance of your rigging will improve its lifespan and maintain its performance. Rinse ropes and cordage with fresh water and mild detergent, if necessary. Lubricate and clean hardware components using marine-grade products, following the manufacturer’s guidelines.

When to replace

Advantages and impact of advanced synthetic materials , advantages of synthetic materials.

- Higher strength-to-weight ratio: Advanced materials like Dyneema, Spectra, and Vectran provide impressive strength while remaining lightweight, ensuring a secure connection and control in an easy-to-handle braid

- Low-stretch and abrasion resistance: These materials are incredibly resistant to stretching, providing improved control and accurate responsiveness. They also maintain their integrity and durability in wear, abrasion, and weathering.

- Increased lifespan: Synthetic materials can endure harsh conditions and resist UV damage.

Impact on Sailing Experience

The use of advanced materials like Dyneema, Spectra, and Vectran has had a profound effect on the sailing experience, with benefits including:

- Improved sail control and responsiveness: These low-stretch materials allow precise, user-friendly, and efficient sail handling and adjustments, leading to better overall performance.

- Enhanced durability and reduced maintenance: High-performance materials resist wear and weathering more effectively, increasing the lifespan of rigging and lowering the frequency of maintenance or replacement.

- Greater performance potential: Advanced materials’ increased strength and lightness improve boat performance to higher levels, especially in competitive racing scenarios.

Troubleshooting Common Problems

- Tangled or twisted lines: angled lines can impede adjustments and create hazardous situations, like tangled jib sheets , which can cause control issues with your headsail. Always coil and store lines properly when not in use to solve this issue. Regularly inspect your lines for twists or tangles, and address them before they become problematic.

- Jammed or stuck hardware: Dirt, corrosion, or damage can cause hardware components like blocks or winches to jam or stick, making it difficult to control the lines. Clean and lubricate your hardware according to the manufacturer’s guidelines to fix this issue. Replace any damaged or worn-out components to ensure smooth operation.

- Lines slipping or not holding tension: Runners may sometimes slip from cleats or winches, causing the sail to lose its desired shape or position. To overcome this issue, ensure you use the proper cleating or winching techniques, and double-check the compatibility of your line materials with your hardware.

When to call a professional

Although boat owners can resolve many rigging issues, there are situations where the expertise of a professional rigger may become necessary. Consider consulting a professional when:

- You feel uncertain about your ability to diagnose or fix a problem safely and effectively

- You need to replace or install new running rigging components that require specialized knowledge or skills

- You have encountered complex issues that may require advanced troubleshooting techniques

The Art of Knots and Splices

Importance of knots and splices.

Knots and splices connect rigging components, secure lines, and adjust sails. Proper knowledge and execution of these techniques allow us to:

- Effectively connect lines and hardware

- Quickly and safely secure or adjust lines under various conditions

- Reduce the risk of lines slipping or coming undone while sailing

- Maintain the integrity and strength of our rigging

Commonly used knots and their uses

Numerous knots are available for various purposes within the rigging. Some of the most common and versatile knots include: