Brian Thompson (sailor)

British yachtsman (born 1962) / from wikipedia, the free encyclopedia, dear wikiwand ai, let's keep it short by simply answering these key questions:.

Can you list the top facts and stats about Brian Thompson (sailor)?

Summarize this article for a 10 year old

Brian Thompson (born 5 March 1962) is a British yachtsman. [1] He was the first Briton to twice break the speed record for sailing around the world, and the first to sail non-stop around the world four times. He is highly successful offshore racer on all types of high-performance yachts, from 21-foot Mini Transat racers to 140-foot Maxi Trimarans. [2]

He started his career in the OSTAR in 1992 with his own yacht. He sailed a lot on multihulls with Steve Fosset with whom he set several records, mainly the around the world sailing record in 2004.

In 2005, he won the Oryx Quest , round the world crewed race, on Doha 2006 , ex- Club Med . In 2006, he won the Volvo Ocean Race on ABN AMRO One as a crewmember of Mike Sanderson . The same year, he finished 6th in the Route du Rhum , in IMOCA class. He finished 5th of the Vendée Globe 2008–2009 on a 60 feet IMOCA class Bahrain Team Pindar [ fr ] . [3]

In 2012, he won the Jules Verne Trophy as helmsman and trimmer for Loïck Peyron , on the maxi-multihull Banque Populaire V . [4] He then became the first British sailor with four non-stop laps of the world.

Caterham Challenge

Following the announcement in April that Brian had joined MGI in the role as sailing director, [5] MGI announced on 15 May 2013 that Caterham Technology and Caterham Composites, part of the Caterham Group , have joined with MGI CEO Mike Gascoyne and MGI Sailing Director Brian Thompson to run a Class40 offshore racing campaign under the banner of "Caterham Challenge". [6] [7]

This two-year campaign follows on from Mike's successful 2012 solo transatlantic aboard a "Caterham Challenge" branded Class40. The Campaign objectives are to bring F1 standards of technology and logistics to off-shore racing, to encourage green, sustainable and reusable energy technologies in the marine, automotive and aerospace sectors and to utilize Caterham's extensive experience in F1, R&D, engineering, competitive sailing and sports marketing. [8]

MGI built an Akilara RC3 Class40 and launched the racing boat in late August. Caterham Challenge was first on public display during the Southampton boat show 2013 followed by sailing and training in The Solent and the English Channel.

The racing calendar for "Caterham Challenge" includes the Transat Jacques Vabre 2013, the Grenada sailing week and the Caribbean 600 in early 2014, together with the Global Ocean Race, leaving from the Southampton Boatshow in September 2014 around the world. [9] [10]

Caterham Challenge started at the Transat Jacques Vabre on 7 November 2013 with Mike Gascoyne as skipper and Brian Thompson as co-skipper, leaving Le Havre, France for Itajai, Brazil. [11]

- [2] "Welcome to the Caterham Challenge" . Archived from the original on 13 June 2013 . Retrieved 18 May 2013 .

- [3] "My Sport: Brian Thompson, Vendee Globe offshore racer" .

- [4] Brian Thompson breaks round-the-world record

- [5] "MGI » Who We Are" . Archived from the original on 3 December 2012 . Retrieved 17 May 2013 .

- [6] "Caterham to back Mike Gascoyne's sailing campaign - SportsPro Media" . 25 June 2013.

- [7] "Caterham F1 boss Mike Gascoyne to join world of ocean racing" . Independent.co.uk . 15 May 2013.

- [8] "What can sailing learn from F1?" . BBC Sport .

- [9] "Caterham Challenge - A powerful new force" .

- [10] "Caterham to back Mike Gascoyne's sailing campaign - SportsPro Media" . 25 June 2013.

- [11] "Caterham Challenge: Mike Gascoyne looks ahead to the Transat Jacques" . Independent.co.uk . 31 October 2013.

External links

- Official website

- Maxi Trimaran Banque Populaire V

- MGIconsultancy.com

- CaterhamChallenge.com

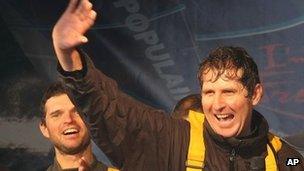

Yachtsman Brian Thompson Describes Jubilation After World Record Circumnavigation Of The Globe

A British sailor told today of his jubilation after he broke the world record for the fastest circumnavigation of the world in any type of yacht.

Brian Thompson, who wrote daily blogs about his experience, said he was "quite emotional" about his achievement and is considering writing a book about his adventure.

Thompson was the only British crew member on board the Banque Populaire V that completed the journey after 45 days, 13 hours, 42 minutes and 53 seconds.

The 14-strong crew of the 40-metre maxi-trimaran crossed the Jules Verne Trophy finish line at Brest, France, at 10.14pm on Friday, smashing the existing record of 48 days, 7 hours, 44 minutes and 52 seconds by nearly three days.

Thompson, 49, who is based in Southampton, chronicled the trip on an online blog on his mobile phone, attracting thousands of followers on the social networking site Twitter.

"Sometimes I think it would be cool to write a book about a trip like this and you could use the blog as a basis for it.

"There are so many more things that happened, like conversations with people, that you want to remember," he said.

A flotilla of boats and crowds on the dock welcomed the crew home and Thompson, who has sailed more than 100,000 miles with American adventurer Steve Fossett, said that he'll miss the crew after spending so much time with them.

"It was quite emotional crossing the line and realising what a bond you made with the guys and especially the three others you're on watch with because you tend to see those people the most.

"You spend two thirds of 45 days together with them so that's a lot of time. You have to rely on them for your safety," he said.

The yachtsman described his teammates, who hail from a number of countries but all share a knowledge of the French language, as "talented, industrious, dedicated, fun and welcoming to an English guy with schoolboy French".

He added: "To achieve my dream of finally holding the Trophee Jules Verne...feels absolutely fantastic. At the same time, to become the first Briton to sail around the world non-stop four times is just amazing and feels very special."

The crew had already broken four speed records on this journey around the globe - one to the equator, one to the Cape of Good Hope, one to Cape Leeuwin, and one from equator to equator.

Thompson cited the stretch up the South Atlantic, past Argentina, Uruguay and Brazil, as his favourite of the trip due to the pleasant weather and said the whole journey allowed him to see "real wonders of the natural world".

He is a real lover of being out at sea and his blog gives readers an insight into what life was like on an isolated vessel in the middle of the world's oceans.

"I really do enjoy being at sea. Some people that go racing, they like it for the racing and see the wet and the cold as something they have to put up with, but I actually really enjoy the tranquility of it, as well as the racing," he said.

The low points of the trip came when the crew lost two days due to weather delays both in the Pacific and North Atlantic and when they missed spending Christmas and New Year ashore with family and friends. Instead, Thompson had a Christmas pudding made of energy bars made for him by the team.

Thompson has been racing two and three-hulled speed machines for 20 years notching up 25 sailing records, and plans to beat his personal best in this year's Vendée Globe solo race around the world in which he came 5th in 2008.

From Our Partner

More in news.

- CLASSIFIEDS

- NEWSLETTERS

- SUBMIT NEWS

Trio of Sailing Legends join Doyle Sails UK business

Related Articles

Brian Thompson 'ecstatic' after breaking world record

- Published 7 January 2012

"Like all things, it happened in a pub," said record-breaking yachtsman Brian Thompson, reflecting on how the idea to travel around the world was first dreamt up.

Speaking from Brest in France, the 49-year-old, from Southampton, said the trip of a lifetime came after a chance meeting at Cowes on the Isle of Wight with Kevin Escoffier from Banque Populaire.

"He was looking for experienced round-the-world sailors, so I got invited onboard to do some short trips," said Thompson.

His boat, the 40m-long maxi-trimaran Banque Populaire V, crossed the Jules Verne Trophy finish line in Brest at 22:14 GMT on Friday, smashing the existing record by nearly three days.

As a member of the 14-strong crew on board, Thompson himself broke the world record for the fastest circumnavigation.

'A real dream'

Mr Thompson, whose job onboard the boat was as helmsman and trimmer, said: "I was driving the boat, which was a real dream, and helping with all the sail changes and trimming the sails."

By crossing the finish line in a total of 45 days, 13 hours, 42 minutes and 53 seconds, he has also become the first Briton to circumnavigate the globe non-stop for a fourth time, beating existing records held by fellow Hampshire sailors Dee Caffari and Mike Golding.

A flotilla of boats and crowds on the dock welcomed the 14 crew back to Brest.

"We saw the lights from about 20 miles out and everyone was just ecstatic," he said.

"I was so happy. It's my fourth time around the world non-stop, this has been the best, on the fastest boat in the world."

The circumnavigation had to be completed unassisted, with only human power manning the boat - with no electric or hydraulic winches.

He said: "Eighteen years ago the record was 79 days and now we've got it down to 45 days. It was an incredible run, we were ahead of the record most of the way.

"It was the trip of a lifetime, we saw some amazing sights, icebergs, comets and albatross, but I am very glad to be back on land."

The yachtsman has been racing two and three-hulled speed machines for 20 years and has notched up 25 sailing records.

"I am looking to do the next Vendee Globe, I think I have two more laps of the planet in me," he said.

Thompson in record-breaking crew

Related Internet Links

International Sailing Federation

Yachting World

- Digital Edition

VIDEO: take our exclusive video tour of MOD70 trimaran Phaedo³, primed for the Caribbean 600 record

- Elaine Bunting

- February 23, 2015

Brian Thompson shows us round the MOD70 trimaran Phaedo³, in which he and the crew are hoping to break the Caribbean 600 record

Racing sailors like to say that if you want to win, then take a gun to a knife fight. US sailor Lloyd Thornburg has got himself an appropriate weapon in his new boat, MOD70 trimaran Phaedo3. Get a tour of this phenomenal trimaran here.

With a rock star crew of Michel Desjoyeaux, Brian Thompson, Pete Cumming and Sam Goodchild, Thornburg is aiming to blaze round the RORC Caribbean 600 race to line honours, and hopefully to set a new course record this week. The record of 40 hours 11 mins has stood since 2009, when it was set on an ORMA 60 trimaran.

To say she’s fast would be a huge understatement: the boat made the crossing from Brittany to Antigua in February in just over nine days.

In this video, Brian Thompson takes us on a tour of the new Phaedo (Thornburg’s previous regatta weapon was a Gunboat 66). Brian shows us the curved foils and explains how they work, the rotating and canting wingmast, and the hydraulic systems that depower the mainsail and are an essential safety feature on this massively powered up multihulls.

The video also shows what the accommodation looks like below – small, but with everything needed for offshore racing.

Commenting on his new project, Thornburg says:

“Brian Thompson and I have been working on getting a MOD 70 for two years and it only came to fruition in January. Phaedo 3 sailed direct from France, across the Atlantic. She was originally Foncia, skippered by Michel Desjoyeaux and Michel will be racing with us for the RORC Caribbean 600. Brian Thompson put all the crew together and from what he has told me about Michel, he is an extraordinary sailor.

“For me this race is just fantastic, once you have gone around this course fast, you just want to go faster and that is the real driving force behind the MOD70. As far as the record is concerned, the boat and the crew are capable of beating it but we will wait to see what the conditions are like for the race and we know we have to finish the course before we can start talking about record pace. Besides keeping our eye on the competition, we will be watching the clock for sure.”

- Yachting Monthly

- Digital edition

Brian Thompson receives Order of Bahrain

- April 15, 2009

British Vendee Globe skipper honoured by King

Bahrain Team Pindar’s record-breaking yachtsman, Brian Thompson was yesterday awarded the Order of Bahrain, from The King of Bahrain, His Majesty King Hamad bin Isa Al Khalifa. The prestigious accolade was awarded for the British skipper’s historic completion of the Vendée Globe solo, non-stop, around-the-world yacht race – the first time a yacht carrying the King’s name and the Kingdom of Bahrain livery, has sailed around the globe.

Thompson, 47, who is visiting the Kingdom of Bahrain for the first time since completing the race in February, was presented to the King at a special reception in Manama, attended by other senior Bahrain representatives.

The King praised Thompson for his outstanding achievement and for promoting the Kingdom of Bahrain to a global audience.

On receiving the award, Thompson said: ‘I am immensely proud to receive this award from His Majesty King Hamad. It was an honour and a privilege to sail around the world on a yacht bearing both his name and the national identity of the Kingdom of Bahrain. Throughout the race I received tremendous support from people throughout the Kingdom and this visit has afforded me a wonderful opportunity to thank many of them in person.’

On November 9, 2008, Thompson embarked on the biggest race of his career, setting sail from Les Sables d’Olonne on the West Coast of France on his first ever solo circumnavigation. Just 11 of the original 30 skippers completed the 28,000-mile voyage and after a total of 98 days at sea, Thompson returned to a hero’s welcome, finishing in fifth place.

- Crew Login Forgotten Password

Enter your details below for the race of your life

Select a race

Gavin Reid ‘honoured’ with nomination for prestigious YJA Yachtsman of the Year Awards

25 October 2016

Mission Performance round the world crew member Gavin Reid, 28, has been shortlisted alongside world leading sailors for the industry renowned 2016 boats.com YJA (Yachting Journalists' Association) Yachtsman of the Year Award, and Young Sailor of the Year Award.

Gavin, (pictured receiving the Henri Lloyd Seamanship Award at Race Finish with his team mates) who is nominated alongside 2016 Olympic Finn Class Gold Medalist Giles Scott and Round the Island Race record setter Brian Thompson, says: “It is a real honour to have made the final three for 2016 boats.com YJA's Yachtsmen of the Year alongside such titans of the sport as Brian Thompson and Giles Scott, and also to be nominated for the Young Sailor of the Year Award. I am overwhelmed by the amount of praise I have received for taking part in the rescue, though to me it pales in comparison to the achievements in yachting that others have accomplished over the year.

(Gavin pictured in the yellow drysuit climbing the mast to rescue the crew member at the top of the mast)

Gavin Reid and his Mission Performance crew were competing in Race 6 of the 14-stage Clipper 2015-16 Race, from Hobart to the Whitsundays, Australia, when an SOS was picked up from a yacht which had a crewman stuck at the top of the mast.

Mission Performance was the nearest to the stricken vessel and Skipper Greg Miller and his crew immediately abandoned their Clipper Race campaign to assist. Gavin, who was born deaf in both ears and had zero sailing experience prior to signing up for the Clipper Race had developed into a watch leader on board. He volunteered to swim from the Clipper 70 to the other yacht where he found four of the crew onboard incapacitated and unable to help their crewmate who had been tangled in halyards at the top of the mast for several hours. Using the one remaining staysail halyard, Gavin was able to hoist himself two thirds of the way up the swinging mast, then climbed the rest of the way hand-over-hand to reach the crewman, untangle the lines and help to lower him down safely. Mission Peformance then returned to the Clipper Race and were provided redress points for the incident before completing the remaining nine races of the circumnavigation. On arrival back to London in July this year Gavin was also awarded the race's Henri Lloyd Seamanship Award. Clipper Race Chairman Sir Robin Knox-Johnston, four time winner of the YJA Yachtsman of the Year Award, says: “Gavin Reid’s nomination for the YJA Yachtsman of the Year and Young Sailor of the Year Awards are highly deserved. Not only did he make a very courageous and selfless decision to help a fellow yachtsman in need in challenging circumstances, he also continually impressed me throughout the entire circumnavigation. “One of 40 per cent of our Clipper Race crew who had no previous sailing experience, Gavin was a natural and fast became a very integral member of his Mission Performance team. I hope his experiences and this recognition inspire him to continue to pursue future sailing opportunities.”

Established in 1955, the Yachtsman of the Year Award is one of the top yachting honours. Previous winners of the award include Sir Robin Knox-Johnston, Dame Ellen MacArthur and four-time Olympic gold medallist Sir Ben Ainslie. The Young Sailor of the Year Award was first awarded in 1993. Fellow Yachtsman of the Year Award nominee Giles Scott from Portsmouth capped a remarkable three-year unbeaten record in the Finn singlehander class by winning gold at the Rio Olympics. In doing so, he also retained his Finn Gold Cup world champion title for the third successive year, and also played a significant role as bowman and tactician aboard Britain’s Land Rover BAR America’s Cup challenge, which leads the Louis Vuitton America’s Cup World Series going into the last event at Fukuoka, Japan on November 18.

Brian Thompson from Southampton, one of Britain’s leading multihull skippers, stormed round the Isle of Wight to break this year’s JP Morgan Round the Island Race record, completing the 50 mile distance in 2 hours 23 minutes 23 seconds in the MOD 70 trimaran Phaedo 3. Then in August, Thompson and his eight-strong Phaedo 3 crew repeated the performance to break the outright record with a time of 2 hours, 4 minutes 14 seconds – an average of 24.15 knots.

The other finalists for the 2016 boats.com Young Sailor of the Year Award are 15 year old 2016 Topper world champion Elliott Kuzyk, Tom Darling (18) and Crispin Beaumont (18), Bronze medalists at the 2016 29er World Championships, and powerboat racer Thomas Mantripp (15), who won this year’s GP RYA British GT15 and British Sprint Championship titles.

Ian Atkins, President of boats.com, says: “The open nominations process for these two awards highlighted the number of exceptional achievements that we have witnessed in 2016. Creating a shortlist of just three nominees for each category is never easy. We already look forward to announcing the YJA's winner in January 2017.” The winners of these premier British achievement awards will be announced at a gala luncheon on Tuesday, January 10, 2017 at Trinity House, London following a vote among members of the Yachting Journalists’ Association (YJA).

Related Stories

21 Mar 2024

Qingdao ETAs

Please see below the latest ETAs for the fleet's arrival in Qingdao (correct as of 0100UTC on 21/03/24)Please note…

20 Mar 2024

Meet the Clipper Race Officials: Sean Liu

With the Clipper Race fleet docking in two stops in China, Zhuhai and Qingdao, what better time to introduce Clipper Race’s Liaison in China, Sean Liu. Sean has been a member of the Clipper Race Office for more than twelve years, spanning five race editions,…

12 Mar 2024

Goodbye Zhuhai!

As the fleet departs Zhuhai, the lively departure ceremony saw the marina walls lined with hundreds of spectators, including Jiuzhou…

20 Oct 2016

Winning Skipper Brendan Hall on Team Spirit

Brendan Hall led the Spirit of Australia crew to overall victory in the Clipper 2009-10 Race, when aged 28. It was the second of three times the trophy has gone to an Australian team. Following the win, Brendan wrote the book

30 Jul 2016

Clipper Race prizes awarded at London ceremony

The Clipper 2015-16 Race prizes have been awarded at a ceremony in St Katharine Docks following the conclusion of the…

Mission Performance diverts to offer aid to yacht

UPDATEMission Performance has resumed racing after diverting from its racing course to offer aid to a non-Clipper Race yacht which…

LOFT SPOTLIGHT: Doyle Sails Solent

Just over a year ago, British sailing legends Peter Greenhalgh, Adrian Stead and Brian Thompson became part of the team at Doyle Sails Solent. As the home to one of the biggest sail lofts in the UK, the ultra-modern, 1000 sqm facility in Universal Marina on the River Hamble is about the size of four tennis courts which provides the capacity to build and service several sails at any one time.

While Doyle Sails has had a well-recognised presence in the UK since 1997, this brand-new facility, its location and talented team are taking Doyle Sails to a whole new level. A passionate and experienced group of sailors and sailmakers are committed to making your sailing more enjoyable, consistently delivering durable, reliable and easy to handle sails, every single time.

Positioned on the River Hamble, Doyle Sails Solent is very close to the Solent, the Isle of Wight, Portsmouth and other key sailing hotspots on the South Coast of England – a region which truly represents the heart of British sailing.

“The most renowned events are Cowes Week and the Round the Island Race, along with the Isle of Wight race which goes past Portsmouth, Lymington and the southern coast,” said Grand Prix and Superyacht expert, Peter Greenhalgh.

“There is a rich history of sailing talent in the River Hamble region, and we have the pleasure of enjoying the most competitive yacht racing in the country, right on our doorstep. Due in part to the fact we have the best weather here in the south and in turn that tends to build up the racing component which we can do almost all year round.”

Greenhalgh, an early participant in the Extreme Sailing Series which ran from 2007 to 2018, is regarded as the most successful sailor from the series. Having won four overall titles including the very first season in 2007 as well as 2015. He and the current Doyle Sails Solent team continue to provide sails for all Grand Prix racing yachts, club racing teams, One Design classes and coastal cruisers. Their location means that they can also work with and service some of the most impressive Superyachts in the world.

“One of the main reasons we joined up with Doyle Sails International was because of Mike Sanderson – we wanted to be a part of the team that he is building,” Greenhalgh said. “Doyle Sails’ focus has always been on people, and building the best team that we possibly can to support the teams we work with”.

Doyle Sails Solent is a loft full of many talents, alongside Greenhalgh is Brian Thompson a well recognised British yachtsman. Brian made it into the history books by becoming the first (and only, so far) Briton to break the round the world sailing record twice as well as the first to sail around the world non-stop four times.

Brian is a vastly experienced and successful offshore sailor and was part of the Volvo Ocean Race winning team with Mike Sanderson’s ABN AMRO One crew in 2005/06. Brian has sailed a great many short-handed boats including Minis, Class 40s and IMOCA 60s, in which he completed the 2008 Vendee Globe. Lately, he has focused on large multihulls, especially MOD70s and 100ft+ multihulls.

“The calibre of the people who are involved with Doyle Sails and the way they work, fits with our ethics – and, Doyle sails are very competitively priced.”

Greenhalgh anticipates that as they continue to develop their new team, they will continue to grow and diversify to best suit their customer’s needs. “We came together as a team in April 2019, and so we are still developing and growing. We are currently finishing sails for a Sunfast 33, alongside a large service job on a Discovery 58 amongst several others”.

Greenhalgh notes that the teams’ affiliation with big boat sailing around the world has always been a big part of what they do. “We work a lot with the major Superyacht shipyards in the UK and love to be able to sea trial inventories for yachts being built out of yards like Pendennis. All three of us [Thompson, Stead and Greenhalgh] do a lot of Superyacht racing which is both a challenge and good fun with some very, very large teams on board.”

Complementing both Peter and Brian is Adrian Stead who has a wealth of Grand Prix racing experience and is a 14 time World Champion with teams such as RAN, Bella Mente, Mascalzone Latino and Quantum Racing. The Two-time Olympian and America’s Cup sailor has also got an Admirals’ Cup win, double Rolex Fastnet Race win and many other offshore race wins to his credit.

From Superyachts and Grand Prix race yachts right through to club racers and cruisers, Doyle Sails Solent have an expert team of sailors and sailmakers that are ready to join your team to help make your sailing more enjoyable.

Learn more about Doyle Sails Solent HERE.

Idaho Falls news, Rexburg news, Pocatello news, East Idaho news, Idaho news, education news, crime news, good news, business news, entertainment news, Feel Good Friday and more.

Kohberger murder trial judge will hear grand jury challenges mostly out of public’s view

Kevin Fixler, Idaho Statesman

MOSCOW ( Idaho Statesman ) — Attorneys for Bryan Kohberger, the man charged with murdering four University of Idaho students last fall, will argue at hearings Friday that their client’s indictment by a local grand jury should be thrown out on several procedural grounds, but only one of which will be debated in public.

Kohberger’s defense team in July filed a request to dismiss the indictment for what they contend was an error in the instructions given to the grand jurors. A month later, they submitted another filing to the court that cites four more legal challenges of the indictment that pushed the capital murder case to trial.

The procedural concerns Kohberger’s public defense raised last month include claims of grand jury bias, as well as the use of improper evidence and a lack of sufficient evidence to indict. The defense also alleged misconduct by the prosecution over its withholding of evidence from the grand jury that the defense says would disprove Kohberger’s guilt.

The defense filed those four follow-up challenges to the indictment under a court-approved seal, which keeps the details of the arguments hidden from the public. The prosecution’s objection also was held under a court seal.

Already, the use of a grand jury by state prosecutors is an intentionally secretive process. Defendants, their attorneys and the public are not permitted to attend. In turn, the defense is unable to cross-examine witnesses or object to certain evidence.

Latah County Prosecutor Bill Thompson sat the grand jury exclusively to review the Kohberger case, and it was presided over by retired Judge Jay Gaskill, previously of Idaho’s 2nd Judicial District in Nez Perce County, according to court records. Under Idaho law , only 12 of the 16 selected grand jurors must support indicting a defendant.

The grand jury met over three days and indicted Kohberger on May 16, the court records showed. He was arraigned on May 22, when he stood silent and declined to enter a plea , leading Judge John Judge of Idaho’s 2nd Judicial District in Latah County, who is overseeing the case, to default to not guilty.

The indictment vacated Kohberger’s scheduled June preliminary hearing, where a judge otherwise determines whether probable cause exists to move a case to trial. If the grand jury challenge is successful, the case likely would revert to a preliminary hearing, an alternative the defense offered in the challenge to the grand jury instructions.

Kohberger, 28, is accused of stabbing to death the four U of I students at an off-campus Moscow home in November 2022. The victims were seniors Kaylee Goncalves and Madison Mogen, both 21; and junior Xana Kernodle and freshman Ethan Chapin, both 20.

At the time, Kohberger was a graduate student in Washington State University’s criminal justice and criminology department. WSU is located in Pullman, about 9 miles west of Moscow.

Kohberger is charged with four counts of first-degree murder and one count of felony burglary. Prosecutors intend to seek the death penalty if a jury convicts him.

Kohberger’s attorneys, in their argument against the instructions received by the grand jurors, asserted that the standard of proof in the Idaho Constitution demands the same level as a conviction at trial: beyond a reasonable doubt. Historically, the language has been interpreted to require the lower legal threshold of being more likely guilty than not, or what is known as probable cause. The same legal threshold is required to obtain a search warrant or make an arrest.

Jay Logsdon, one of Kohberger’s public defenders, in the defense’s filing implored Judge to rule for his client, which would support Idaho’s past efforts at “adopting reforms to the grand jury system intended to restore to that system its function as bulwark for freedom.”

Edwina Elcox is a Boise-based criminal defense attorney who formerly served as an Ada County deputy prosecutor. She commended the creativity of Kohberger’s public defenders in filing the legal threshold challenge but voiced doubts it would succeed.

“Obviously, it’s thoroughly researched and is a novel legal argument,” Elcox told the Idaho Statesman in a phone interview. “But this is a loser motion before this court, and that’s the reality of the situation.”

The defense’s argument was unlikely to prevail at least in part because it would overturn the longstanding legal standard for an indictment, retired Idaho Supreme Court Chief Justice Jim Jones previously told the Statesman . He described the effort as “some kind of Hail Mary thing.”

Judge will hear those arguments Friday afternoon. The defense’s other four legal claims aimed at tossing the grand jury indictment, however, will be debated during a morning session that is closed to the public, at the defense’s request and with no objection from prosecutors, court records showed.

All grand jury records, including transcripts and the jury selection list, are typically filed under court seal. The day after the indictment, Thompson also obtained a court order from Magistrate Judge Megan Marshall, who handled the Kohberger case in its early stages, to seal the names of the witnesses who testified before the grand jury .

At least two of the victims’ families recently voiced frustration about how information about the case has been released to the public as they advocated for maintaining cameras inside the courtroom. Judge has yet to issue his decision from a hearing on the matter last week.

Shanon Gray, attorney for the Goncalves family, issued a statement to the Statesman on behalf of his clients, as well as some members of the Kernodle family.

“This case is surrounded by secrecy. Everything is either sealed or redacted,” which leads to speculation, the statement read. “That speculation is fueled by the secrecy surrounding everything that is filed and every hearing that is closed off to the media and the public.”

The inherently secretive nature of grand juries makes assessing the potential at successful challenges difficult, Elcox said. But she questioned the need to restrict public access for the entirety of the hearing on the defense’s four more recent claims, given some are legal arguments over process.

“If the challenges are to individual grand jurors, then I can see the need to protect identities,” she said. “I can at least understand the theory behind that portion of it. But if they’re challenging irregularities like the prosecution did something wrong, I don’t know why you’d want that sealed.”

Even so, of the four arguments that the public won’t get to watch — and not knowing the specifics of the evidence-based challenges — Elcox said the defense’s best possible chance of overturning the indictment would be assertions of bias from the local grand jury.

“That’s where it’s likely going to be because you’re dealing with an extremely small community, where a large portion of revenue and employment is literally centered around that college,” she said. “Getting an unbiased, neutral grand jury in that county just on face value would be extremely difficult. So if I had to pick a horse to bet on, it would be that one.”

Even if Judge rules in favor of the defense on any of its five arguments, the state’s prosecution of Kohberger is not going away, Elcox said.

“Even if they were successful, all is not said and done here,” she said. “Per the defense’s own request, their alternative remedy is to remand it for a preliminary hearing, which also is a probable cause hearing.”

SUBMIT A CORRECTION

Caitlin Clark and Iowa find peace in the process

An Iowa associate professor breaks down the numbers to display Caitlin Clark's incredible impact on women's college basketball. (2:08)

ON A COLD, snowy Monday night in January, Caitlin Clark walked into a dimly lit restaurant in Iowa City and looked around the room for her parents. They smiled from a back table and waved her over. It was her 22nd birthday. Three teammates and the head Iowa Hawkeyes manager were with her, and soon everyone settled in and stories started to fly -- senior year energy, still in college and nostalgic for it, too.

That meant, of course, tales of The Great Croatian Booze Cruise.

In summer 2023, as a reward for their Final Four season, the Iowa coaches arranged a boondoggle of an international preseason run through Italy and Croatia, grown-ass women, pockets thick with NIL money to burn. They saw places they'd never seen, spoke strange languages and walked narrow cobblestone streets. "One of the best nights was when we got bottles of wine and just sat on the rooftop of the hotel," Caitlin said.

On the last free day of the trip, they proposed a vitally important mission to head manager Will McIntire, who now sat at the birthday table next to me.

They needed a yacht.

Like a real one, the kind of boat where Pat Riley and Jay-Z might be drinking mojitos on a summer Sunday. So McIntire found himself with the hotel concierge looking at photographs of boats. He asked Caitlin about the price of one that looked perfect.

"Book it right now," she said.

They climbed aboard to find a stocked bar and an eager crew. The captain motored them out to nearby caves off the coast of Dubrovnik where the players could snorkel and float on their backs and stare up at the towering sky. They held their breath and swam into caves. They looked out for one another underwater. When stories of the Caitlin Clark Hawkeyes are told years from now, fans will remember logo 3s, blowout wins and the worldwide circus of attention, but players on the team will remember a glorious preseason yacht day on crystal blue waters, a time when they were young, strong and queens of all they beheld. They'll talk about the color and clarity of the sea. A color that doesn't exist in Iowa. Or didn't until Caitlin Clark came along.

The Booze Cruise lived up to its name. After the stress of a Final Four run and the sudden rise of Caitlin's star, it was a chance to be a team and have nobody care and to care about nobody else. Many of their coaches didn't even find out about the yacht until the team got home.

"It was just what we needed," McIntire said at the birthday dinner table. It was the kind of night parents dream of having with their grown children. Often three conversations were going at once. Caitlin's dad, Brent, was telling McIntire about the wild screams and curses that come from their basement when one of their two sons is playing Fortnite.

"You should hear her play Fortnite," McIntire said, pointing to Caitlin.

"Is she good?" Brent asked.

"No," he laughed.

Caitlin told a story about her freshman year roommate almost burning the dorm down trying to make mac and cheese without water. She and Kate Martin told one about both of them oversleeping the bus at an away game -- they awoke to both their phones ringing and someone knocking on the door as they made eye contact and shouted "S---!" in unison.

There was one about Caitlin in full conspiracy-theory rage, too, convinced that Ohio State had falsified her COVID-19 test result to keep her out of a game.

"This is rigged!" she told her mom on the phone. "They're trying to hold me out!"

Anne took over the narration.

"Call the AD!" she said, imitating her daughter.

"I did not say that!" Caitlin said.

There was the time Caitlin needed to pass a COVID-19 test for games in Mexico. She showed up in the practice gym, throwing her mask on the ground while waving her phone and crowing, "I'm negative, bitches!" ... until one of her teammates looked at the email and realized Caitlin had read it wrong, so she quickly grabbed her mask and bolted. As the stories flew, Caitlin smiled, loving to hear her teammates, happy to be with them.

We raised glasses again and again, and her dad beamed. Her mom kept thanking her teammates for taking such good care of her. They toasted to Caitlin, to CC, to 22 and to Deuce-Deuce. The waitress brought over a framed collage she had made, along with a note thanking Caitlin for inspiring "girl power."

Caitlin's mom made a final toast.

"Happy birthday," she said.

"Happy birthday, Caitlin," Kate Martin said, turning to her left and asking her, "What was the best thing that happened in Year 21?"

Caitlin thought about it for a second.

"Final Four," she said.

Everyone clinked their glasses.

"Not even the booze cruise?" one of them asked.

They all laughed.

"Booze cruise!" everyone shouted.

MY INTRODUCTION TO Caitlin Clark's world began in September over breakfast with Hawkeyes associate head coach Jan Jensen, who grew up on an Iowa farm before building a basketball legend of her own.

We met at an old-guard Jewish deli while Jensen was on a brief Los Angeles recruiting trip, flying in from Alaska that morning and flying back home that night. We ogled the cake case with the towering meringue pompadours but settled on something healthy, along with about a million refills of coffee. Jensen held a cup in her hands and summed up the challenge now of being Caitlin Clark.

"She's figuring out how to really live with getting what she's always wanted," she said.

Jensen smiled before she continued.

"She wants to be the greatest that ever was."

She pointed at me as if to underline her meaning.

"I believe that in my heart," she said.

Jensen averaged 66 points a game in high school in the days when girls played 6-on-6. She is in Iowa's girls high school basketball Hall of Fame. Her grandmother, Dorcas Andersen Randolph, who went by "Lottie" because she scored a lot of points, is too. Jensen still has her uniform. She sees Caitlin standing on the shoulders of generations of women like Lottie.

She also understands Caitlin is standing on no one's shoulders.

"She's uncensored," Jensen said. "So many times women have to be censored."

Jensen leaned across the table again.

"There is something in her," she said. "Unapologetic."

To Jensen, Caitlin seems immortal; young, talented, dedicated, rich, famous and on the rise.

"She's 21," she said.

A magic age, her confidence and talent startling to older people like me and Jensen.

"Don't ever let anyone steal that from her," Jensen said. "Protecting that is the coach's job."

Jensen spoke with pride of Caitlin's 15 national awards, but she also said she is so talented, and driven, that she sometimes struggles to trust her teammates. This would be the work of this season and the epic battle of Caitlin's athletic life. She sees things other people do not see, including her teammates. She imagines what other people even in her close orbit cannot imagine, has achieved what none of them have achieved and has done so because she listens to the singular voice in her head and her heart. She must protect that and nurture it. At the same time, she is learning that her power grows exponentially when it lives in concert with other people. A great team multiplies her. A bad team diminishes her. The trust her coaches ask her to have in her teammates, especially new ones, comes with great personal risk. Believing in her coaches requires faith and courage. For their part, the Iowa coaches know that they are holding a rare diamond and are constantly reminding themselves their job is to polish, not to ask her to cut to their precise specifications. It's an effort, possession by possession, game by game, practice by practice, to meld two truths, to find the right balance, to elevate.

"It's a work in progress," Jensen said.

After last season's run to the NCAA title game, the Hawkeyes lost their star center, Monika Czinano, who's now playing pro ball in Hungary. She started every game Caitlin had ever played except one, and her dominance in the post taught Caitlin how successful teammates created space and opportunities at other spots on the floor. She still talks to Monika. Her trust in Monika's replacements is the Hawkeyes' most fragile place this year and will say a lot about whether this team can return to the Final Four.

"That's gonna be the struggle for her," Jensen said.

This idea would, in the coming five months, create two narratives for me, one public, one private, one about a superstar standing on center stage surrounded by an ever-growing mania, and another about a young woman trying to find herself, trying to decide how and who she wanted to be , in the center of that madness.

The waitress warmed up our coffee.

Jensen said she'd introduce me to Caitlin as soon as there was time in her schedule. Then she slipped out of our booth and headed out for a scouting visit at a nearby high school. I had a meeting with Priscilla Presley for another project later that day across town. We talked about life in the fishbowl with Elvis. She told me about how only a handful of memories remained hers alone even all these years later. I thought about Caitlin somewhere 30,000 feet in the air on a plane home from New York City after she received her final award of the 2023 season.

THIS IS A STORY about being 21. Do you remember turning 21?

At 18 you feel immortal but just three years later, a crack has opened in that immortality. You feel the gap between ambitions held and realized. You're aware that wanting things badly enough won't always be enough. You guard against bad energy and thoughts and hold fast to every ounce of confidence. That's when life really begins.

The size of Caitlin Clark's stage and the scale of her dreams and the reach of her talent leave little margin for error. She is chasing being the best of all time, which is an isolating thing. She isn't scared to voice her ambitions even when they separate her from the people she loves. Her teammates dream of merely making a WNBA roster. Kate Martin did the math for me one evening. There are 12 teams. Each team has 12 roster spots. College basketball might be a bigger public stage than the professional league, but it is much easier. The normal dream of a 21-year-old women's college basketball player, then, is the nearly impossible task of finding just one of 144 spots on a WNBA team, which has nothing to do with normal. A lofty dream might be to win one national award, not 15. When Caitlin gave her Associated Press Player of the Year trophy to her parents, her mom looked inside and gasped -- some of the metal on the inside was already peeling and rusting.

"What happened?" she asked Caitlin.

Caitlin shrugged sheepishly.

"The managers got it," she said.

It turns out the trophy, her mom said with a shake of the head, holds two beers. (Actually, the managers fact-checked -- it's two hard seltzers.) Caitlin is grateful for the awards but got tired of traveling around to get them, not because she didn't appreciate the attention but because she seemed to sense that her survival and continued success would depend in part on her closing the book on last season. The past is dangerous to an ambitious 21-year-old. It was a struggle to get her on the plane to New York City to accept the AAU's prestigious Sullivan Award. She asked whether it couldn't simply be mailed to her instead. In the end, she and her family had 12 hours in the city so she wouldn't miss any class. Michael Jordan talks about this -- the speed at which things come at you, the way, when you look back, it becomes hard to remember what happened where and when. That's Caitlin Clark's world right now, and inside she feels both like a superstar and like the little girl begging her father to expand the driveway concrete so she'd have a full 3-point line to shoot from. She references her childhood a lot in public, revealing comments hiding in the plain sight of news conferences and one-on-one interviews.

"I feel like I was just that little girl playing outside with my brother," she says.

The Clarks landed in New York and went straight to their hotel. Thirty minutes later, Caitlin hit the lobby dressed for the show. She signed autographs, posed for pictures, received the Sullivan Award, took more pictures, gave a speech and took more pictures. The family had just a few hours to sleep before heading to the airport for the flight home. But it was her first trip to New York City, and Caitlin said she wanted to see Times Square and get a slice of pizza. They went out and took a photograph, everyone together, then watched as Caitlin ordered a pepperoni slice, which arrived greasy on a stack of cheap paper plates. She folded it like a veteran. In the morning, they flew home. Caitlin rode with her headphones on. She likes Luke Combs. Turned up. Hearts on fire and crazy dreams. The next day she'd be at morning practice and then take her usual seat in Professor Walsh's product and pricing class.

IN MID-OCTOBER, I got to Iowa City in time for the second practice of the year. I ran into head coach Lisa Bluder in the elevator down to the Carver-Hawkeye practice gym, and she laughed about how two fans from Indiana just showed up at the first practice and were walking onto the court taking selfies. Bluder had to stop practice and politely ask, you know, what the hell? They explained they had traveled far to see Caitlin Clark in person.

At 8 a.m., practice began, and almost immediately Caitlin was vibrating with anger at the referees, who were actually team managers with whistles. The whole team looked out of sorts -- "little sh--s," one of their assistants called them during a water break -- and Caitlin fought her temper as several of her young teammates made mistakes. The main object of her scorn was a sophomore named Addison O'Grady , No. 44, who had become a bit of a punching bag. And all the while she raged at what she thought was the terrible job being done calling fouls and traveling.

"Stop letting him ref!" she barked to Jensen about a manager on the baseline. "He's not calling anything!"

She jacked up a 3.

"I don't love that 3," Bluder told her. "You were in range, no doubt. But you were not in rhythm and were contested."

Now Caitlin started talking to herself. What is the offense right now? This is a pretty regular thing, Caitlin Clark talking to Caitlin Clark, scolding her, cursing her, complaining to her, because who else could understand?

"Call screens," she muttered.

"We must call screens," Bluder yelled. "Somebody's gonna get hurt. Somebody's gonna get rocked."

Then Caitlin touched her leg gingerly, which set off a chain reaction of anxiety and hushed attention. She took herself out of an end-of-game drill to rest it. Then, unable to resist, ended up in the drill anyway.

At the end of practice, Bluder described the long road awaiting them if they wanted a return to the Final Four. The promised land, she called it. Everyone on the team knows that Caitlin has given all of them a challenge, yes, but also a gift. An opportunity to breathe rare air. Caitlin's best requires their best, and if they give it, they might just be able to beat anyone.

"Caitlin's got a hell of a lot of pressure," Bluder told them. "I get it."

But it was more than that.

"We are her," she said.

I MET WITH CAITLIN a few minutes later. We found some chairs in the Iowa film room.

"I'm trying to learn about myself as a 21-year-old," she said. "About how I react to situations, what I want in my life, what's good for me, what's bad for me."

The back wall of the film room featured larger-than-life portraits of the Hawkeyes, with Caitlin dominating the center of the collage. She gets the absurdity. Most every person walking around on the planet is a watcher. A consumer of the lives and adventures of others. Caitlin was like that, standing in line as a little girl to meet a hero like Maya Moore. In her bathroom at home in Des Moines she kept a caricature she got at an amusement park that shows her wearing a UConn uniform. But during last year's NCAA tournament, when she averaged 31.8 points and 10.0 assists in leading Iowa to the championship game, she became one of the watched .

"... and I'm 21 years old!" she said, shaking her head and shrugging her shoulders with a grin, as if to say: Buy the ticket, take the ride.

"I don't f---ing know."

She's a household name now. Nike puts her on billboards like Tiger or Serena. She is the best women's college basketball player in the country, and one of the best college basketball players period . She has designs on best ever, a fraught thing to want. She admires Kobe Bryant and Michael Jordan, apex predators, and her ambition and talent live within her in equal measure alongside her youth and inexperience. She is striving for agency and intent in the glare of a white-hot spotlight. Luke Combs commented on her social media a few hours ago. She got free tickets and backstage passes to see him over the summer and also got tickets to Taylor Swift's "The Eras Tour." She invited the biggest Swifties on the team, trying to use her new superpowers for good. The Hawkeyes are forever asking her to DM their celebrity crushes and invite them to games. She laughs and tries to explain why she can't get Drake to Iowa City. A local newspaper reporter recently asked her about LSU's Angel Reese being in a Sports Illustrated swimsuit spread, a trap question asking her to comment on the marketability of their bodies.

She earns seven figures and has deals with Bose, Nike and State Farm. The Iowa grocery store chain Hy-Vee, another corporate partner, sometimes pays for her private security at public events.

Meanwhile, her mother still does her laundry.

"I'm trying to learn about myself," Caitlin repeated.

"At the same time I have to be the best version of myself. I have to be the best version of myself for my teammates, and for the fans, and for my family ... "

She laughed again.

"Yeah," she said, pausing to find the right words, feeling the weight of the coming season.

"Yeah," she said again.

Having been to the Final Four last year doesn't make another Final Four easier. It makes it harder. Fame is a warm saccharine glow that obscures the terminal velocity of expectation. "That adds to the tension," she said. "Every failure feels that much more intense. And every success also feels that much more intense. So it's about finding balance."

She sounded like an old soul, knowing how precious these days of glory are and how they are already slipping between her fingers. But that might just be because a middle-aged man was the one doing the listening. Most likely she is experiencing time in an altogether different way, so that right now, all at once, she is living with last year's almost , with this season's grind and hope, and with the knowledge that if everything goes right there is a future in which every year will be harder than the one before, and every season the watchers will be ready to replace last year's model with some newer, shinier object.

"When I leave this place, I don't want people to forget about me," she said.

THAT SAME MONTH, Brent and Anne Clark, who could only look at each other in wonder, parked in the West 43 lot next to the football stadium, where that afternoon their little girl would be playing an exhibition outdoors at Kinnick Stadium in front of the largest audience to ever watch a women's college basketball game.

"It's wild," they kept saying over and over.

"This is all she ever wanted!" Anne said as we set up the food and drinks. "She's asked for years: 'Can we please do a tailgate?'"

Brent stopped and listened to the band practicing inside the stadium. They played "Wagon Wheel." He found a spot where the sun felt warm on his face.

"So what's up with these sandwiches?" asked Caitlin's older brother Blake.

Her younger brother Colin hooked up the portable speaker. He's a freshman at Creighton, where he has found a community of his own. He and his sister adore each other. When he was a baby, the family called her "Caitie Mommy" because she took such good care of him, and now Brent and Anne love to see him celebrate her success. The first track he played was AC/DC's "Back in Black," the Hawks' football walkout song. Anne reached for a cardboard cutout of Caitlin's beloved golden retriever, Bella, a leftover from her freshman season when COVID-19 meant no fans in the seats.

Brent threw a football with one of the young family friends. Around him other fathers did the same with their sons and daughters, many of them wearing No. 22 jerseys, girls and boys.

"Look at all these little girls going in," Anne said.

Some football players walked through the parking lot, and nobody paid them much mind. Former Iowa and NFL star Marv Cook stood talking with Brent about Caitlin and her teammates when the football guys went past.

"They're not the only show in town anymore," Cook said.

The Clark car was packed with Hy-Vee fried chicken sandwiches, cookies, a cooler of beer and soda, these strange pickle-ham-cream cheese concoctions, the most Midwestern thing you've ever seen in your whole life -- "soooo gross!" Caitlin said later.

The lieutenant governor of Iowa stopped by to pay his respects.

"Hawk Walk!" he said.

Everyone went to form a line of cheering fans as the Iowa bus parked and the players went into the stadium. Anne Clark worked herself close holding up the cutout of Bella so Caitlin could see. One of the little girls next to Anne treated her like a Mama Swift sighting at a show.

"She touched me!" she screamed to her friends.

Caitlin went into the football locker room to get ready. Outside, the stadium pulsed with energy. Walter the Hawk swooped down from the press box. Then the dozens of speakers ringing the main bowl started thumping. "Back in Black" again. The whole place shook. Caitlin stepped into the light pouring into the mouth of the tunnel.

"I-O-W-A!" the crowd chanted.

"Let's hear it for No. 22, Caitlin Clark!" the announcer called.

Someone started an M-V-P chant.

The wind blew across the court. Caitlin even air-balled a free throw. Nobody cared. She got a triple-double. Stayed focused. With a minute left she threw a pass that center Addi O'Grady fumbled. Caitlin twirled around and hung her head but went back to her on the next possession.

The game ended in a blowout, and then Caitlin started working her way down the front row of the sideline, more than 50 yards of little girls and boys. They took selfies and asked her to sign their shirts. One young boy held a sign that said, "Met you at Hy-Vee."

"Thank you for coming!" Caitlin yelled.

As she finally ran into the tunnel, she jumped up and high-fived a young girl.

"No way!" the girl said.

Caitlin made it to the locker room, where she had stored a gift a very sick child had given her. The kid was a patient at the children's cancer ward across the street and was serving as an honorary captain. She'd had her own baseball card made, and on the back she'd been asked to name her favorite Hawkeye. Caitlin Clark, she said.

"I'll keep that forever," Caitlin said.

She left the stadium through a side door, got on the back of a golf cart with her boyfriend and headed to the basketball arena, where her parents waited with an enormous bag of freshly washed and folded clothes.

ONE MORNING LAST YEAR I drove across Des Moines to see where all this began. Although Caitlin hasn't been a student at Dowling Catholic for almost four years, her presence -- and her family's presence -- remains palpable in the halls. Her older brother won two state titles in football. Her younger brother won a state title in track. Caitlin's grandfather, her mom's dad, was the beloved football coach there for years. Once after an emotional game he gathered his team at midfield and burned Des Moines Register articles about his team he didn't like.

Caitlin comes by her fire honestly.

I parked and met the basketball coach, Kristin Meyer, in the lobby adjacent to the chapel. We walked through the library to her office. She told me a story that stuck with me. In 10th grade, Caitlin got a reading assignment about empathy. She didn't know what the word meant. Meyer tried and failed to explain. She realized then that she had a team of girls who wanted to enjoy playing sports -- "for fun," Caitlin would tell me later -- and one ponytailed Kobe Bryant.

The summer before her freshman season, the team went to a camp at Creighton. Caitlin threw a three-quarter-court bounce pass that hit a teammate in the hands. That same game, she bopped down the court and threw a perfect behind-the-back pass. Also in rhythm and on the money.

"I would go back and watch film and just rewind and watch again and watch again," Meyer said.

When Caitlin saw a player come open, or more often realized that a player would be coming open momentarily, look out! The ball was in the air and flying at their heads. This made her teammates nervous, and they'd shut down, which Caitlin didn't understand. Soon she just stopped passing.

"It was hard for her to understand what other people would feel," Meyer said.

Caitlin was, in real time, learning how to use her gift. This is an old story among basketball greats. Magic Johnson threw passes that even James Worthy couldn't catch. Caitlin's task was to see the gulf between her potential and her reality and close that distance. Often she got impatient. With herself and others. When someone made a mistake, or if she thought a referee or a coach was being unfair, she'd have tantrums. Mostly she seemed unaware of how her body language and mood impacted the people around her. She'd throw her arms in the air in disgust, or clap loudly, and waves of nervousness would pass through the team. Of course that cut both ways. When she praised a teammate, the coaches would see that player swell with pride. "If Caitlin gave me a compliment," one of her teammates said, "I felt like I was the best player in the gym."

Meyer started showing her film of her body language, something the Iowa coaches still do. They'd sit down and watch in silence as Caitlin stomped and gestured.

"High school basketball was honestly harder for me than college," Caitlin told me. "I mean that in the most positive, respectful way to my teammates. The basketball IQ wasn't there. At the end of the day they didn't care if we won or lost, really. It wasn't gonna affect their life that much. They just didn't get it on the same level."

Meyer watched a Bobby Knight video in which he called the bench the greatest motivator. That resonated. So when Caitlin would fire some wild shot she could see in her mind but not quite execute with her body, Meyer would sit her. Three times in high school Caitlin got technical fouls and she'd immediately come out, once for an entire quarter. As soon as she hit the chair she'd start agitating -- "Can I go back in?" "Can I go back in?!" "CAN I GO BACK IN?" -- until Meyer relented.

"When I used to get technical fouls in high school," Caitlin said, "I did not want to come out of the locker room after the game because I know my mom would be mad. But if I got one during an AAU tournament, I don't think my dad would tell my mom. He knew my mom would not be happy, but he understood it from a competitive standpoint."

Her dad played basketball and baseball in college. He sees a lot of himself in her.

"To her everything is a competition," Brent Clark said. "I was that way when I was her age. I was really ..."

He thought for a moment.

"Emotional," he said finally.

He wishes his own parents would have punished him more for his outbursts in youth sports. He remembers with shame crying in a dugout.

"I get her," he said. "I can relate. I see a lot of that fire. She's just much better at controlling it than I ever was."

Brent and Anne want most of all for Caitlin's spirit to never be squashed. Her grandfather the Dowling Catholic football coach used to say, "It's a lot easier to tame a tiger than it is to raise the dead."

Brent and I sat at a little sandwich place near his office, where he is a senior executive at an agricultural industrial parts company. He laughed talking about the Dowling Catholic Powder Puff girls' football game.

"What did she play?" I asked.

He looked at me like I was an idiot.

"Quarterback."

He laughed at the memory of taking Caitlin out in the back yard and watching her throw a perfect pass, a dart, 20 yards on the fly.

"You couldn't have thrown a better spiral."

Caitlin, like most children, watched her parents much more closely than they realized. "They balance each other really well," she said. "The biggest thing is he's always been a constant. I literally cannot say one time my dad has raised his voice at me. My mom is somebody I talk to every single day. My life would be a mess if it weren't for her. She's one of my best friends."

Caitlin led the state in scoring a couple of times, but Dowling never won a state title during her career. Her senior year the team didn't even make the state tournament. She could shoot the Maroons into games and sometimes out of them. But nobody worked harder in the gym. She wanted to be great. When someone got in the way of that, even if that someone was her, she struggled to manage her emotions. An engine as rare as hers threw out a ton of exhaust.

Caitlin and I talked about high school one morning. Both Jensen and Kate Martin told me they didn't think she had any true friends outside her tight-knit family before she got to Iowa. They didn't mean she wasn't popular, or didn't have a group to hang with, only that there was no one in her orbit who was wired like her. Legends like Tiger Woods and Joe DiMaggio often seemed alone too, even surrounded by huge crowds, solitary citizens living in a world of their own ambitions and fears.

"Were you lonely?" I asked.

She thought about it.

"I would say I was lonely in the aspect of no one understood how I was thinking," she said. "I wasn't surrounded by people who wanted to achieve the same things as me."

Letters from college coaches stacked up at her house in those days. Her parents kept them from her until late in the process, trying instinctively to protect as much of her childhood as they could. I think they knew even then. Her dream school was, like everyone else, UConn. She was growing up and learning for the first time about being watched, about reputation. A lot of college coaches watched the same body language sequences Meyer did. Most didn't mind. Dowling's open gyms filled with the best of the best coaches in the country. One absence was conspicuous, though.

"Geno never came," Meyer said.

CAITLIN'S FAMILY, IT'S important to note here, is quite Catholic. She went to Catholic school from kindergarten through graduation. Anne comes from a big, loud, fun Italian family, and if you look in Caitlin's fridge at the apartment she shares with teammate Kylie Feuerbach , you'll almost certainly find some frozen red sauce meals made by her mom or grandma.

Her brother Blake is always texting her reminders to say her rosary and go to the church near campus, conveniently located across the street from Iowa City's great dive bar, George's -- which is where Coach Bluder and her staff go to celebrate big wins. My friend Annie Gavin, whose father is the famous wrestling coach Dan Gable, goes to that church and reports that more Sundays than not, she sees Caitlin in the pews. Blake wore his St. Benedict bracelet to the Final Four last year and did four decades of his rosary at the hotel and the last round in the arena just before tipoff.

You see where this is going.

Anne Clark grew up the daughter of a Catholic high school football coach. What do you imagine she thinks is the greatest, most magical university in the world?

"For a while I thought she was gonna end up at Notre Dame," Meyer said.

Meyer told me that Caitlin remained pretty calm during her recruitment -- except when Notre Dame coach Muffet McGraw came to town.

Her list of choices winnowed to two. The Hawkeyes and the Fighting Irish. She'd also looked at Iowa State, Texas and both Oregon schools. The lack of interest from UConn stung. "Honestly," she said, "it was more I wanted them to recruit me to say I got recruited. I loved UConn. I think they're the coolest place on Earth, and I wanted to say I got recruited by them. They called my AAU coach a few times, but they never talked to my family and never talked to me."

Bluder and Jensen had been worried about the Irish from the beginning. Jensen got to Brent Clark when Caitlin was in the seventh grade and told him they'd offer her a scholarship right now. Then she promised to stay away until he was ready to talk. She also predicted exactly how the rest of the nation would awake to the magic of his daughter, which gave her credibility as the years went on.

When Caitlin was playing in Bangkok with Team USA in 2019, Jensen and Bluder flew to games around the world so Caitlin could see they made the effort.

"My family wanted me to go to Notre Dame," Caitlin said. "At the end of the day they were like, you make the decision for yourself. But it's NOTRE DAME! 'Rudy' was one of my favorite movies. How could you not pick Notre Dame?"

Everyone in her high school wanted her to choose Notre Dame. Every year the top two or three students went to South Bend. It was ingrained in the culture. When she went on a campus visit, she wanted to love it. In fact, she got frustrated with herself for not loving it.

Notre Dame it would be. She called McGraw. It was the "smart" choice.

Next she called Bluder to break the bad news.

Bluder was at a field hockey game.

She stepped away from the field and called her staff.

"We're not gonna get her," she said.

Then the Iowa coaches waited for the dagger of an official announcement. For some reason it never came. Jensen had seen second-guessing before. She texted Caitlin's assistant AAU coach to see if it would be appropriate for her to reach out.

"I think I'd call her if I were you," the coach told Jensen.

So she did.

"What's up?"

"I haven't seen anything."

"Yeah, I've changed my mind."

Caitlin wanted to come to Iowa but thought her mom didn't want her to turn down Notre Dame. The AAU coach called Bluder and asked if Caitlin were to change her mind, would there be a spot for her. Three or so days later Caitlin again faced two phone calls. The first was terrifying. She needed to tell McGraw she had changed her mind.

"I'm 17 years old," she said, "and I'm sitting in my room and I'm sweating my ass off. I'm about to call her. She is an intimidating individual. She was really understanding. She kinda knew. She was great. Then I called Coach Bluder."

Dave and Lisa Bluder sat in the cozy basement of a fancy local restaurant. A fireplace warmed the room. They'd just sat down and ordered a drink.

"I can remember the exact table," Bluder said.

Her phone rang.

"Do you have a few minutes to talk?" Caitlin asked.

She committed on the spot. Bluder went back inside and ordered a bottle of champagne. Then she and Dave got another bottle and caught a ride to Jensen's house to celebrate some more. Caitlin remained in her bedroom, still nervous. She had made her two calls, but there was one more person who needed to know the news.

"Caitlin commits to us but didn't tell her mom," Jensen said laughing.

Her parents both call the family meeting that followed "emotional" and say they realized, truly in that moment, that their daughter had a vision for herself more ambitious and nuanced than any they could conjure. She seemed vulnerable and brave, and they deferred to her judgment.

Caitlin Clark was going to be a Hawkeye, and she told reporters her goal was to take Iowa to the Final Four. Some people rolled their eyes, but a bar had been set. Caitlin and I talked about this moment, the way that it felt like part of her search was to find other young women who cared about the game as much as she did. I asked her if this moment felt like the first decision she'd made completely herself.

"For sure," she said.

I asked if this was also the first time she had ever defied her mother, whom she adores -- a critical step on the path from childhood to adulthood. She stopped cold. It seemed like she'd never really thought about it before but now saw it clearly, from the high ground of the life she has built from talent and desire.

"Probably," she said finally.

THESE DAYS CAITLIN and her teammates travel around Iowa City in a pack, a tight-knit crew, as her celebrity pushes them further and further into their insular little world, which revolves around the riverside apartment complex where most of them live. They know everything about each other -- such as, say, that Caitlin's fake name for orders and hotel rooms is Hallie Parker from "The Parent Trap" -- and this past Halloween, they dressed in costumes and climbed up balconies to sneak into teammates' apartments to scare each other. Sydney Affolter nearly had a heart attack when she approached her sliding balcony door to find, staring at her, a full gorilla costume with a giddy Kate Martin inside.

These women are Caitlin's tribe, and they have been since she arrived on campus in fall 2020. The starting five for the first game of her career was the same as the starting five in the national championship game three years later. Monika Czinano, the center, a dominant force on the court, with a quirky Zen off it. "Well, I live on a floating rock," she'd say with a shrug after a tough loss. McKenna Warnock holding down the 4 with physicality and smarts, and Gabbie Marshall playing alongside with power and finesse. Caitlin ran point from her very first practice, while Martin began to shape the whole team in her competitive image, the daughter of a high school football coach who brought intensity to every part of the game.

"What she found is people who also put their entire life into basketball," Martin said.

Caitlin's teammates meanwhile discovered her talent came with impatience and temper. She blew up at practice. A lot of throwing her hands up in the air, stomping off the court and simply refusing to pass the ball to an open teammate if she didn't believe they'd deliver. It was the first time in her life she'd had to play with teammates who would not simply be run over. Warnock got in her face. So did Martin. The coaches pulled her aside. She's open. You have got to pass her the ball. Caitlin's answer, like a logical toddler, left them stuttering to find a response. Why would I pass her the ball when I'm taking more shots in the practice gym?

"I had expectations of them and they weren't meeting them," Caitlin said.

Because of COVID-19, all this occurred in private in the early days. A lot of the freshman year dust-ups happened in empty arenas. Her teammates came to understand that they were dealing with someone like Mozart. She wasn't rude, nor necessarily nice, just a different species. At one point that year a sports psychologist came in to work with the team. She started going around the room and asking the players when they felt stressed and anxious and how they reacted to those feelings. One by one, the young women described familiar symptoms and scenarios: sweaty hands, a fear of the free throw line, struggling with breathing, anxiety about the last possession.

Finally it was Caitlin's turn. She seemed a little embarrassed.

"I never am," she said.

Everyone in the room somehow understood she was being more vulnerable than cocky.

"Stone cold," one witness told me. "It was so cool."

I pressed her once on how she must have seemed to her teammates that first year. "People know I'll have their backs and I'll ride for them every single day," she said. "Obviously there is a switch that flips when I step on the court like I want to kill someone. I'm here to cause havoc. Some of the biggest challenges are I have all this emotion, I'm a freshman and I'm starting and how do I channel this? At times they were definitely like, 'Why is this girl a psycho?'"

The Hawkeyes lost games they should have won that year, still figuring out a way to have both a team and a superstar. The coaches put together video sessions completely devoted to her reactions. They had few notes about her actual play. She simply moved at warp speed, and even her most gifted teammates needed time to adjust. To learn how to breathe her air, to speak her language, to cross dimensions from their old world into the new one she was creating.

"If you see a practice, you might figure that out," Jensen told me once. "You gotta have whatever that is. You gotta be playing the game at Caitlin's pace. It's all processing. She's a half-second ahead."

The coaches saw her learning, too, looking to pass out of double- and triple-teams. Bluder kept telling them to give her latitude. Their main job, as she saw it, was to make sure they never put "her light under a bushel."

One day last year I sat down with Jensen to watch film of Caitlin's outbursts, which they had put together in reels.

"She does a lot of twirling," Jensen said with a sigh.

A twirl, a stomp off the court, slamming her hands into a wall. A reaction when the mistake was someone else's and not often enough a "my bad" when it was hers.

"She's not touchy-feely," Jensen said. "You're gonna meet her where she is."

The Iowa coaches didn't baby their prodigy. After one particularly bad performance, Caitlin caught a full barrage of anger and blame in the postgame locker room. She took it in public, but when she got into the car with her mom, she burst into tears. Not because of the yelling but because she wondered if she wanted something different than everyone else around her.

"Our goals are not aligned," she told her mom.

The Hawkeyes won 20 games and lost 10 her freshman year. They got beat in overtime at home by Ohio State. They beat No. 7 Michigan State in the Big Ten tournament. Caitlin won national co-freshman of the year. That helped with credibility.

"I want her in my foxhole," Martin said. "That's the type of player you want at the end of a game in a battle."

Maybe earlier than anyone, Martin realized that Caitlin's emotional outbursts were a byproduct of a young woman trying to marshal forces too powerful to fully control. Caitlin could take them to glory if they could help her be her best self. They all needed one another. Her teammates' understanding grew. They saw her get the blame for all the losses and knew the ball would always be in her hands with the game on the line. At a team meeting that season, when hurt feelings over Caitlin's lack of trust had come to the surface, it was Martin who rose to speak.

"I got something," she said.

The team fell silent.

"Everybody thinks they want to be Caitlin," she said. "I don't know if you want to be Caitlin."

The women knew immediately what she meant.

"The crown she wears is heavy."

The other four starters slowly accepted their role as The Caitlinettes. They won two games in the NCAA tournament before getting beat in the Sweet 16 by UConn. The headlines the next day back in Iowa would ratchet up the pressure -- Are the Hawks Ahead of Schedule? -- but in the postgame chaos Caitlin saw a familiar face approaching. It was Geno Auriemma. He told her how great she'd played and thanked her for her contribution to their sport. It felt like a victory. He finally saw what Bluder had seen all along. "He could see the greatness in me when I was a freshman," she said, "before everything unfolded when I was a junior."

That offseason Caitlin tried out for Team USA. Possession to possession, shot to shot, she played free and bold. Head coach Cori Close, whose day job was coaching the UCLA Bruins , saw the confidence immediately. "Women have been socialized to not want to take all the shine," she said. "She is an elite competitor who isn't scared to step into the moment."

But every team Caitlin had been on during the tryouts had lost its scrimmage, and after tryouts Close pulled her aside and put a question to her simply: "Do you want to be a really talented player who gets a lot of stats, or do you want to win?"

Caitlin made the roster, led the team to gold and was named MVP. "To Caitlin's credit, she really bought into that," Close said. "She went from being a really, really talented competitor to a winner."