7 Best Sailboat Autopilot Systems

Last Updated by

Daniel Wade

June 15, 2022

Essential in increasing efficiency, safety, and convenience, marine autopilots are a sailor's best friend when out there on the water. A properly operating sailboat autopilot will keep your sailboat on a selected course even in strong currents and winds and that why you need to go for the best sailboat autopilot.

Steering a sailboat is always fun. And even though many sailors are so good at it, some circumstances can make steering a boat on a straight line or the right course almost impossible. The tides, winds, and the complex hull-bottom designs can throw your sailboat off route and the adjustments that you have to make to return to course can be your voyage killers. Even if you have a crew that regularly sails with you, having an autopilot can help you stay on course and that's exactly why you need the best sailboat autopilot.

In the simplest term possible, an autopilot is an extra pair of hands that can help you in steering your sailboat on the right course. It is a self-steering device for powerboats or sailboats and even the most basic autopilot can help in holding your vessel on a pre-set compass course. Some advanced autopilots can even gather data from your boat and determine whether or not the boat is capable of handling the task in hand.

So whether you have a mechanically-steered boat or a tiller-steered sailboat, an autopilot is of great importance for both you and your boat. And it doesn't matter whether you want to explore your nearest lake for a day or want to sail to the Caribbean on your sailboat, it will make your job a lot easier, efficient, and safer. This is why we've put together this article to help you find the best sailboat autopilot. Read on and find which is best for you and your sailboat.

Table of contents

How to Choose the Best Sailboat Autopilot for Your Vessel

When it comes to choosing the best sailboat autopilot for your vessel, the easiest thing to do would be to go for an autopilot that can steer your sailboat in calm seas. However, this is not advisable since you want an autopilot that works perfectly under very demanding sea conditions. With that in mind, here are the most important things to consider when looking at the best sailboat autopilot for you.

Speed of Helm Adjustment

The best way to measure the speed on an autopilot that's appropriate for your boat is by looking at the number of degrees per second of helm correction. As such a 40-feet boat requires 10 degrees per second, a 25-feet boat requires 15 degrees per second, and a 70-feet boat requires 5 degrees per second.

An above-deck or below-deck Autopilot

Do you want an autopilot that's designed to be used above the deck or below the deck? Well, the most important thing is to choose an autopilot that matches the displacement of your boat. More importantly, above-deck autopilots are ideal if you have a smaller boat while below-deck autopilot is ideal if you have a larger boat.

The Steering System

What type of steering system does your boat have? It's important to understand whether your boat has rotary drives, linear drive, or hydraulic drives.

Control Interfaces

You should choose what's perfect for you as far as the control interface is concerned because this is one of the most crucial parts of an autopilot. The best features to consider include ease of use, waterproof, intuitive display, backlit options, and compatibility with SimNet, SeaTalk, and NMEA 2000.

7 Best Sailboat Autopilots

Here are the 7 best sailboat autopilots.

Raymarine ST1000 Plus Tiller Pilot

(Best for Tiller-steered Sailboats)

The Raymarine ST100 Plus Tiller Pilot is a classic tiller pilot that's one of the best accessories for your sailboat and your everyday sailing escapades. It's designed in such a way that it can accept NMEA data while still offering accurate navigation thanks to its incredibly intelligent software.

This autopilot is designed with a backlit LCD to help you see your navigational data, locked course, and other important information that can make your sailing safer and much better. The fact that the backlit LCD works perfectly in low-light conditions is an added plus.

That's not all; the ST1000 comes with an AutoTack feature that works like an extra hand when you're engaged in other responsibilities. For example, it can tack the sailboat for you when you adjust the sails. Better still, this autopilot is fully-fitted with everything that you need to install it on your sailboat and use it.

- It's easy to use thanks to the simple six-button keypad

- It's perfect when sailing in the calm sea as well as in stormy conditions

- It is waterproof so you don't have to worry about it getting damaged

- Its intelligent software minimizes battery usage thereby prolonging its battery life

- Perfect for tiller-steered sailboats

- The 2-year warranty could be improved

- It's a bit heavier

Garmin Ghc 20 Marine Autopilot Helm Control

(Best for Night Sailing)

If you're planning to go on a voyage, chances are you'll find yourself sailing overnight. With that in mind, you should go for an autopilot that works perfectly both during the day and at night. The Garmin Ghc 20 Marine Autopilot Helm Control is your best sailboat autopilot for these types of adventure.

This amazing autopilot is designed with a 4-inch display that can improve your nighttime readability. This display is glass-bonded and comes with an anti-glare lens that is essential in preventing fog and glare in sunny conditions. This is crucial in helping you maintain control in all conditions, both during the day and at night.

This autopilot also provides a 170-degree viewing angle. This is essential in viewing the display at almost any angle. So whether you're adjusting the sails up on the deck or grabbing an extra sheet below the deck, you can be able to look at the display and see what's going on. So whether a sailing vessel or a powerboat, this autopilot is easy to use thanks to its five-button control.

- The five-button control makes it easy to use

- Comes with a bright 4-inch display

- The display works in all conditions thanks to its glass-bonded, anti-glare lens

- The display offers optimal view both during the day and at night

- It's compatible with other Garmin products

- Only good for sailboat under 40 feet in length

- The battery life should be improved

Simrad TP10 Tillerpilot

(Best for 32-feet or less Sailboat)

For many lone sailors, going with a sailboat that measures 32-feet or less in length is always ideal. Under such scenarios, it's always best to go with a sailboat autopilot that's perfect for such types of boats, and the Simrad TP10 Tillerpilot can be a superb option for you. This autopilot is so perfect as it brings to the table a combination of advanced technological software and simplicity.

Its five-button display makes it user-friendly, easy to use, and perfect in controlling your sailboat accordingly. This autopilot has a low-power draw, which means that your battery will last longer even when used for prolonged periods. This is an excellent autopilot that's designed with the sailor in mind as it goes about its business quietly so that you can enjoy your sailing adventures without noise and interruption from a humming autopilot.

- One of the quietest sailboat autopilots

- The battery life is excellent

- It's designed with one of the most advanced software

- It's waterproof to protect it from spray and elements

- It offers precision steering and reading in all types of weather conditions

- It's easy to use and control

- Not ideal for big boats

Raymarine M81131 12 Volt Type 2 Autopilot Linear Drive

(Best for Seasonal Cruising)

For those of us who love cruising during winter when other sailors are drinking hot coffee from the comfort of their abodes, the Raymarine M81131 is the right sailboat autopilot for you. Well, this autopilot can be an ideal option if your sailboat is large enough to have a full motor system.

This autopilot is one of the most powerful in the marine industry and has an incredible electromagnetic fail-safe clutch. This autopilot is also compatible with other devices such as NMEA 2000 ABD SeaTalk navigation data. In terms of precision navigation, this autopilot will never disappoint you in any weather condition.

So whether you're looking to go ice-fishing or sailing the oceans during winter, this is your go-to autopilot.

- Offers optimal sailing experience and navigation precision

- It's very quiet

- It offers high performance with minimal battery usage

- It's great for adverse winter conditions

- It's expensive

Furuno Navpilot 711C Autopilot System

(Best for Accuracy)

If you're looking for the best sailboat autopilot that will take your navigation to the next level in terms of accuracy, look no further than the Furuno Navpilot 711C. This is an autopilot that enhances your boat's precision as far as staying on course is concerned. This is because the autopilot is designed with a self-learning software program that offers step by step calculations of your navigation and course.

This autopilot also offers real-time dynamic adjustments so that you can steer your sailboat more accurately. Thanks to this self-learning algorithm also offers great power application that significantly reduces the manual helm effort when maneuvering various situations. Its colored graphic display is of great benefit as you can easily read the information even in low-light conditions. So it doesn't matter whether you're sailing at night or during the day, this autopilot will serve you right in any condition.

- It's great for power and fuel efficiency

- The display is intuitive

- It's easy to set up and use

- Its power assist is essential in reducing steering system complexity

- Great for both outboard and inboard motors

- Quite expensive

Si-Tex SP120 Autopilot with Virtual Feedback

(The Most Affordable Autopilot)

If you're on a budget and looking for one of the most affordable yet reliable sailboat autopilots, look no further than the Si-Tex SP120 Autopilot. This is a perfect high-performance sailboat autopilot that can be great for small to medium-sized powerboats and sailboats.

One of the most important features that this autopilot brings to the table is the ability to offer virtual feedback. This is great in eliminating the manual rudder feedback and thereby enhances your sailboat's performance. Its splash-proof 4.3-inch LCD offers one of the best transflective displays in the marine industry. The 4-button operation makes it a lot easier to use and provides the information you need to steer your sailboat safely and perfectly.

This autopilot can be great for you if you have a small or medium-sized sailboat thanks to its ease of use. The fact that it's one of the most affordable sailboat autopilots makes it highly popular with sailors who are on a budget.

- It's simple to install and use

- The virtual feedback is great

- The display is one of the best in the game

- It's quite affordable

- It's not ideal for big boats

Garmin Reactor 40 Kicker Autopilot

(Best for Outboard Motor Boats)

If you have a motorboat that has a single-engine outboard, The Garmin Reactor 40 Kicker Autopilot can be an ideal option. This is a great autopilot that mitigates heading error and unnecessary rudder movement while offering more flexible mounting, which is essential in offering a more comfortable sailing even in the roughest of weather conditions.

This autopilot can be easily fine-tuned thanks to its throttle settings with a touch of a button. Of course, this can be useful especially when the seas are rough and you're trying to remain on course. This autopilot is also waterproof to ensure that it doesn't get damaged with spray or other elements.

With this autopilot, you're guaranteed to enjoy an awesome sailing trip even when going against the wind or when sailing in rough conditions.

- Easy to install and use

- It's waterproof

- It's beautifully designed

- It comes with a floating handheld remote control

- It's great for maintaining heading hold and route.

- It's only ideal for motorboats with up to 20 horsepower

- It's relatively expensive

As you can see, there are plenty of options when it comes to choosing an ideal sailboat autopilot for you. The best thing about the above-described sailboat autopilots is that they're among the best and you can find one that perfectly suits your unique needs and boats. Of course, most of them are quite expensive but they will advance the way you sail and make your sailing adventures even more enjoyable. We hope that you'll find the perfect sailboat autopilot for you.

Until next time, happy sailing!

Related Articles

I've personally had thousands of questions about sailing and sailboats over the years. As I learn and experience sailing, and the community, I share the answers that work and make sense to me, here on Life of Sailing.

by this author

Sailboat Upgrades

Most Recent

What Does "Sailing By The Lee" Mean?

October 3, 2023

The Best Sailing Schools And Programs: Reviews & Ratings

September 26, 2023

Important Legal Info

Lifeofsailing.com is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon. This site also participates in other affiliate programs and is compensated for referring traffic and business to these companies.

Similar Posts

How To Choose The Right Sailing Instructor

August 16, 2023

Cost To Sail Around The World

May 16, 2023

Small Sailboat Sizes: A Complete Guide

October 30, 2022

Popular Posts

Best Liveaboard Catamaran Sailboats

December 28, 2023

Can a Novice Sail Around the World?

Elizabeth O'Malley

4 Best Electric Outboard Motors

How Long Did It Take The Vikings To Sail To England?

10 Best Sailboat Brands (And Why)

December 20, 2023

7 Best Places To Liveaboard A Sailboat

Get the best sailing content.

Top Rated Posts

Lifeofsailing.com is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon. This site also participates in other affiliate programs and is compensated for referring traffic and business to these companies. (866) 342-SAIL

© 2024 Life of Sailing Email: [email protected] Address: 11816 Inwood Rd #3024 Dallas, TX 75244 Disclaimer Privacy Policy

- SAILOMAT 800

- SAILOMAT 760

- Designer's Comments

- Overall Description

- Main Features

- Technical Info

- Component Photos

- Installation Photos

- Questions and Answers

- Pricing Information

- User Comments

- Installation Examples

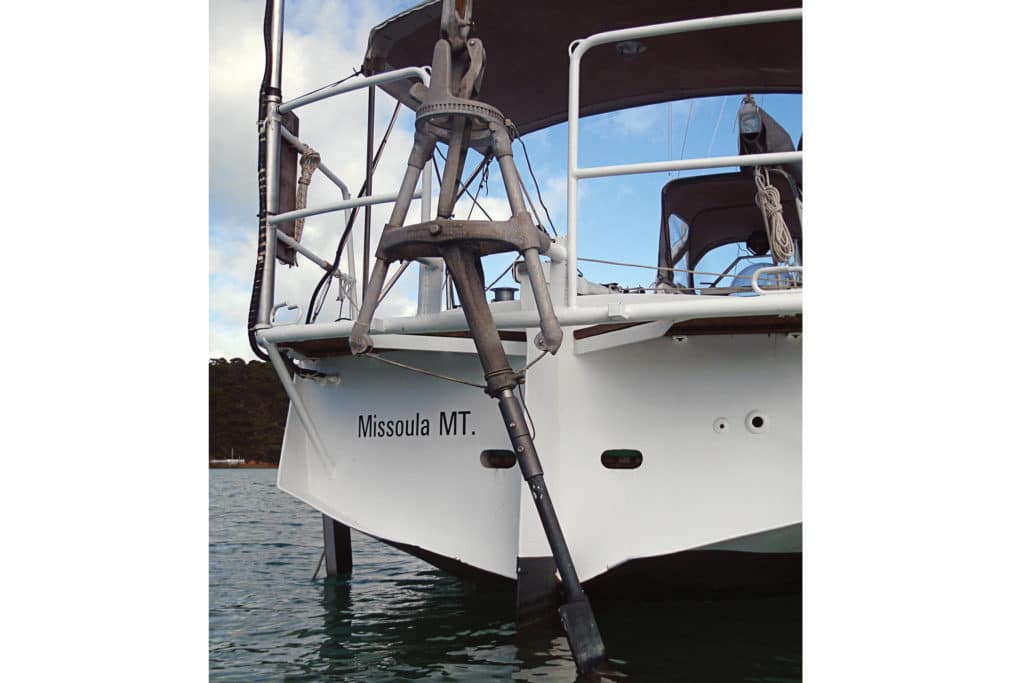

The ULTIMATE in Sailboat Self-Steering

SAILOMAT is the world's leading professional design team and manufacturer specializing in state-of-the-art mechanical self-steering systems for all cruising sailboats.

Universally acknowledged among world cruisers as the most advanced self-steering systems available – a SAILOMAT is a masterpiece of design and function. The very high strength, built-in simplicity, simple mounting, reliability, and long life make SAILOMAT Self-Steering the distinguished leader in its field.

The most recent design is the SAILOMAT 800/760/700 series, based on 40 years of self-steering design experiences , practical testing and manufacturing under the group leadership of Dr. Stellan Knöös, both in Sweden and USA. The state-of-the-art and innovative SAILOMAT 800 system represents the next generation in sailboat self-steering.

The Ultimate in Sailboat Mechanical Self-Steering Custom Design and Manufacturing Worldwide sales Factory Direct Since 1974. San Diego, California, United States www.sailomat.com [email protected]

Steering the dream

Hydrovane is your best crew member: an independent self-steering windvane and emergency rudder/steering system... ready to go!

Hydrovane will fit any cruising boat!

Off-center installations are the norm!

Doubles as Emergency Rudder/Steering!

True Stories

Golden Globe Update Day 113:

[GGR Leader Jean-Luc Van Den Heede sailing the Rustler 36 Matmut] was full of praise for his Hydrovane self-steering. “In a gale it has a big advantage because it is not steering the boat’s rudder, but has its own. This little rudder is far more efficient than the big rudder.”

– Jean Luc Van Den Heede on satellite phone call

“I am happy I did install the Hydrovane, especially that I saw on YouTube that at the same time 2 sailboats almost the same size as mine with the same problem. The crew had to abandon the the ships and left both boats in the middle of the Atlantic and lost everything … again thanks to the Hydrovane. It saved my boat.”

– Jacques Glaser, Amel Mango 52

“My wife and I have just completed a two month cruise with our new Hydrovane and it has performed beyond all expectations… If cruising I wouldn’t go to sea without one: strong, simple, reliable, an emergency helm and an extra crew member who never complains and doesn’t need a watch system.”

– Pete Goss, MBE, Frances 34

“So, I must tell you, and I mean this sincerely, the Hydrovane is simply a game changer for Quetzal. It’s just great and performs better than I expected… One other feature of the vane that I really appreciate is that it eases the load on the rudder and rudder bearings.”

– John Krestchmaer, Kaufman 47

“With just two of us on board, I wanted a system that was simple and effective to operate, and it has exceeded my most optimistic expectations by a considerable margin. It truly is our third crew member.”

– John Mennem, Jeanneau 45.2

“…it is still the most technically elegant solution i have ever seen for a wind vane… I was clawing off a lee shore on one side, and islands on another – winds were reported at 55 knots, and waves in the region were at least ‘boat length’ high and quite steep with the currents. This was an awful night and I was very afraid for myself, the boat and my equipment – I had new found respect, trust and comfort in the Hydrovane after that.”

– Steve De Maio, Contessa 26

In this recent Pacific crossing, the Hydrovane kept us on course (relative to the wind, of course) for several days at a time, requiring no tweaking or attention at all. If you can balance your boat and twist a dial, you can successfully operate a Hydrovane. Don’t leave home without one!

– Bill Ennis, Passport 40

“For the first time, we had to run downwind, under bare poles in gale force 8 conditions, with gusts to 50 knots – and don’t get me started on the sea conditions! Have you ever swallowed your tongue? Oh, and iVane, our wind-steering partner. What a gem! It steered 230 hard miles without even nut rations.”

– Brian Anderson, Hallberg Rassy 40

“The additional cash to purchase a windvane was almost too much… Just how good is this ‘Hydrovane’ anyway?”

After 29,000+ miles: “We’ve said to each many times that without doubt the most valuable piece of equipment on board was Casper – best purchase EVER. I will never own an offshore boat again that does not have this device.”

– Ryan Robertson, T 40

Swim Step / Sugar Scoop

External rudder, watt&sea bracket, other products.

Watt&Sea Hydrogenerator

Echo Tec Watermaker

Happy Halloween! This costume may have been for a different occasion but relevant nonetheless! 👻 “After seeing what Taurus [the Hydrovane] does for us [my friend] fell in love with him too. So much so that when the crew dressed up for the equator crossing, she dressed up as a Hydrovane!” - Norlin 37 owner 🙌🙌 ... See More See Less

- Comments: 1

1 Comment Comment on Facebook

How times change just thought I’d send you this video that somebody sent me that bought a Hydrovane ❤️x

Well that was a fun night. 🎉 Thanks @cruisersawards Young Cruisers' Association for bringing together so many inspirational sailors and story tellers! Get out there and chase the wind ⛵️ #cruiserawards #youngcruisers #internationalcruiserawards #seapeople #annapolis #usboatshow #hydrovane ... See More See Less

- Comments: 0

0 Comments Comment on Facebook

#repost from @kirstenggr ⛵️ “Thinking back on the sailing, and missing it! Thanks to @ hydrovane for having serviced Minnehaha's hydrovane , which did about 45 000 nm before having any major overhaul - possibly more than any hydrovane has ever done before without a significant service. It saw Kirsten and Minnehaha all the way through the GGR and over the finish line! The unit is as good as new again, and it was smooth sailing all the way down to Madeira! Also, a big thanks to Eddie Arsenault, for having built such a solid mounting bracket for the hydrovane ! Without Eddie, Minnehaha would just not be the strong boat that she is today!” ... See More See Less

- Comments: 2

2 Comments Comment on Facebook

Wow, absolutely so proud my fathers invention and so glad everybody is so still going strong with this after so many years!! It is so lovely to see !❤️

Any photos of the mount Eddie made?

Thank you Kirsten Neuschäfer ! You are an inspiration. The Hydrovane loves sailing as much as you do 😀 Kudos to Eddie for the rock solid install! Thinking back on the sailing, and missing it! Thanks to Hydrovane International Marine for having serviced Minnehaha's hydrovane, which did about 45 000 nm before having any major overhaul - possibly more than any hydrovane has ever done before without a significant service. It saw Kirsten and Minnehaha all the way through the GGR and over the finish line! The unit is as good as new again, and it was smooth sailing all the way down to Madeira! Also, a big thanks to Eddie Arsenault, for having built such a solid mounting bracket for the hydrovane! Without Eddie, Minnehaha would just not be the strong boat that she is today! ... See More See Less

Hydrovane is my most trusted crewman.

Lee Colledge Shaun Colledge see what you have built 💪 👌

Once upon a time under spinnaker between Niue and Tonga 😍 ... See More See Less

This week we sailed from Lemvig Denmark to Vlieland Netherlands. 270nm and a tough journey for us and without the Hydrovane it really wouldn't have been possible for us. It gives us peace of mind while sailing and can no longer do without it. Boat is a Barbican 33.

How To Pick the Right Self Steering for Solo Sailing

Self steering is one of the most important considerations for solo sailing and any sailor who is preparing to embark on an offshore voyage. Many people who have never sailed alone believe that single handed sailors spend entire passages glued to the helm, spending weeks on end behind the wheel through heat and gales, only pausing for brief moments to grab a snack or go to the bathroom. Thankfully for solo sailors, the reality is usually quite different.

Most solo sailors have indeed been forced to steer for prolonged periods of time at some point in their careers, but the reality is that most lone voyagers use a windvane or autopilot to steer as much as possible, freeing their time up to take care of the boat and enjoy the passage. It’s one of the greatest beauties about blue water sailing vessels that you can get the boat to sail herself most of the time, which allows the captain to spend his hours navigating, handling the sails, reading, cooking, fishing, singing poorly at the top of their lungs, and enjoying the rare freedom that is only known to people who have been hundreds of miles from the nearest human being.

While preparing to write this guide, I asked eight highly experienced single handed sailors what was the most important piece of equipment they took on their expeditions, and all of them agreed it was their self steering systems.

Whether you choose to equip your vessel with an electric autopilot, a windvane, or simply use sheet to tiller steering techniques, it’s absolutely critical to the success of your voyage to have some kind of self steering mechanism in place to keep your boat headed in the right direction while you sleep or tend to the boat.

In the third and final part of our solo sailing series, we will take a look at self steering for single handed sailors, beginning with a brief history of self steering techniques, moving on to explore different types of self steering available to sailors today, and finally covering how to decide what self steering system is best for you.

A Brief History of Self Steering Techniques

The great pioneer for self steering techniques for solo sailors was Joshua Slocum, an American sailing ship captain who witnessed the dying days of the great age of sail and went on to become the first person ever to sail around the world alone. Slocum’s circumnavigation was completed in the early 1900’s on an old fishing vessel (called the Spray ) that he had refitted for the voyage himself. At the time of Slocum’s solo circumnavigation, sailing alone offshore was so rare that he was often accused of murdering and eating his crew at sea.

When Slocum left Boston to sail around the world, it was agreed upon among sailors that every vessel needed at least one or two crew members in order to keep watch and steer the vessel while the captain slept. Even captains of small fishing or merchant vessels that were only at sea for a day or two at a time brought along a second mate to help handle the boat. Nobody could fathom why he would want to do it alone.

Slocum claimed that the Spray, which in addition to having no crew was also engineless, could hold a steady course on just about all points of sail. He would set the sails so that the boat was well balanced, lash the wheel to account for any lee helm or current, and lie down to sleep – sometimes for hours at a time.

There were instances that he didn’t touch the helm for days at a time, like when he fell violently ill from food poisoning off the coast of Spain. Slocum crawled down below and curled up on the cabin floor in extreme pain. At some point he looked up the companionway and saw a “ghost captain” who he believed had taken control of the wheel to keep the Spray clear of rocks.

Slocum recovered and eventually completed his voyage, returning to Boston three years after his departure. The voyage made him an instant celebrity, and Slocum wrote a book about the voyage which is still in print over a hundred years later. His voyage inspired other solo sailors to attempt the same feat, and each of them dealt with self steering using their own techniques.

As more sailors attempted to replicate Slocum’s solo voyages, it became apparent that not all boats had the same natural ability to hold a steady course as the Spray. Many vessels will steer themselves quite well with the wind forward of the beam, but as the wind moves aft, they tend to become more temperamental, rounding up into the wind. Various techniques were tried to remedy this problem of self steering downwind, often using twin jibs that were connected to the helm via a series of blocks and lines. This technique was used with varying degrees of success, but it never came close to competing with a contemporary windvane or autopilot with regards to ease of use and reliability.

By the 1950’s, solo sailing was taking off as a major sport for challenge seekers and adventurers. A single handed transatlantic race was conceived (which later became the OSTAR race) from England to the United States and solo sailors and their exploits became a regular feature on newspaper headlines from London to New Delhi.

Despite all this interest in solo sailing, self steering was still the greatest single problem for lone sailors. Then Blondie Hastler, one of the competitors in the early races, came up with an invention that would change the world of solo sailing forever.

Hastler designed the first self steering windvane, a device which uses a small sail and auxiliary rudder to keep the boat sailing on track based on the wind direction (see the section “Windvanes” below). Windvanes immediately took off, and within a year or two of Hastler revealing his invention to the world they were already extremely popular among solo and double handed sailors. In 1968, when the Golden Globe round the world yacht race was held, each competitor had some version of Hastler’s self steering system.

Soon, the first commercial units hit the market, and by the 1970’s there were over a dozen manufacturers of windvane self steering units. The early designs had various issues, but each year brought new innovations, and today there are a number of highly proven windvanes available on the market. Some models are strong enough to be guaranteed to hold up for an entire circumnavigation, and I have been told of one Australian circumnavigator using the same Aires windvane for ten different round the world voyages.

Windvanes serve their purpose very well, but the limitations to windvane self steering became more apparent as racing sailboats got faster, in some cases moving faster than the wind. The problem with using a windvane to hold a course when you are sailing faster than the wind is that the apparent wind direction becomes so far from the true wind direction that a windvane cannot hold a steady course. That’s why you never see a windvane on an IMOCA 60 or a 100 foot racing trimaran.

The first time an electronic autopilot was used as a means of self steering for an ocean crossing was in 1936, when Marin Marie traveled from New York to La Havre on his 13-metre motor vessel Arielle. Marie used a primitive version of an electric autopilot to varying degrees of success on his voyage, but it took many more decades for them to become regularly used by boaters. Today, electric autopilots have become the most popular choice for self steering, although windvane self steering remains a favorite for hard core offshore voyagers.

Windvanes for Solo Sailing

A windvane is a piece of equipment that is mounted to the transom of your vessel which uses a small sail and miniature rudder to steer your boat according to the wind direction. The windvane is set so that the wind passes on both sides of the vane. When the boat veers off course, the wind pushes on the side of the vane – causing it to pull on lines which are connected to the steering system via a series of blocks. The whole setup uses no electricity and can operate in anything from six or seven knots of wind to a full blown gale.

There are many models of windvane available on the market, but they are all based on one of two primary types – a servo pendulum or auxiliary rudder. Servo pendulum windvanes use lines connected to the ship’s primary rudder to steer the vessel. Auxiliary rudder windvanes use a smaller separate rudder to steer the boat with the primary steering locked off amidships.

The advantage to a servo pendulum style windvane is that it can be much smaller and better concealed than an auxiliary rudder style unit. In the case of Cape Horn windvanes, the unit can be made to fit with the lines of the vessel so that you barely notice it’s there at all. Cape Horn windvanes also have few moving parts that can break, and they come with a warranty for 28,000 miles or a complete circumnavigation.

The advantage to the auxiliary rudder design is that they don’t need to be connected to the main steering system, and they can also be used as emergency steering if the primary rudder is lost. If your vessel has hydraulic steering or is equipped with dual helms, it’s a good idea to choose an auxiliary rudder type windvane, as they operate independently of the primary steering. This also gives the added advantage of not requiring lines to cross the cockpit, as is needed with most servo pendulum style windvanes.

Electric Autopilots for Solo Sailing

Most cruising boats today are equipped with some type of electric autopilot (which uses a compass course or GPS coordinates to steer the vessel). The reason for this is they are relatively cheap when compared to the cost of a windvane, they are easy to use, and they can usually be installed without any significant changes to the vessel. They don’t change the appearance of the boat and don’t require a large external frame mounted to the transom.

On the other hand, electric autopilots often use a lot of electricity to operate, and are notoriously prone to breakages. I have found autopilots to be the second most common thing to break or malfunction during an offshore passage, after combustion engines.

Of course, if you plan to be doing a lot of motoring, or if you have a racing boat that is capable of sailing faster than the true wind speed, an electric autopilot is the only way to go.

There are three options available for electric autopilots – units that steer using an adapter that attaches to the wheel, units that use a hydraulic ran to move the rudder, and tillerpilots that connect directly to the tiller for smaller vessels. Tillerpilots are by far the cheapest option of the three, and they can be connected directly to the auxiliary rudder or servo pendulum on a windvane to steer a larger boat.

While autopilots are no replacement for a windvane for a long offshore voyage, I believe that an electric autopilot, paired with other self steering options, is an important piece of equipment for modern day solo sailors.

Sheet to Tiller Steering and Other Alternative Techniques

Even on vessels equipped with a windvane or autopilot, it’s important to have a back up plan in case of equipment failure, especially for solo sailors. Prior to departure on your solo passage, it’s a good idea to practice balancing the sails and seeing how your vessel behaves with the wheel lashed on different points of sail.

One alternative method for self steering is sheet to tiller steering, where one of the sheets (usually a jib sheet) is led to the tiller and bungee cords or elastic tubing is used to create some counter tension. This technique doesn’t work for every boat, but it’s worth experimenting with in case your windvane or autopilot breaks at sea. Of course, this only works for boats that have a tiller rather than a wheel.

On solo deliveries, I have often found myself on a vessel with faulty self steering gear. Usually I end up finding a way to balance the boat under sail while upwind, but I have had little luck keeping most vessels on course off the wind. That’s when I end up experimenting with sheet to tiller steering, or bracing myself for long hours at the wheel.

What’s the Best Self Steering for My Vessel? – Making the Final Decision

Investing in the proper type of self steering gear is one of the most significant decisions that you will need to make before embarking on a solo passage. It’s important to read everything you can find about the types of self steering that are available, and talk to other boaters with a similar type of vessel. Ultimately, the ideal setup depends on your size and design of vessel, type of primary steering onboard, and where you plan to sail.

Personally, I believe that pairing a windvane and a small tillerpilot is the best setup for most mid size cruising vessels. The windvane can be used to steer the boat under most sailing conditions, and the tillerpilot can be attached to the servo pendulum or auxillary rudder to steer the vessel while motoring or in light winds. If one system breaks, you can use the other to get to port and make repairs. I think the best choice of windvane is one that also can function as an emergency rudder, like the Hydrovane or Sailomat 3040 systems. That way, you can kill two birds with one stone.

I chose a Hydrovane auxiliary rudder style self steering system for my own boat, and it has performed wonderfully thus far. I would recommend the same to any solo sailor with a mid size cruising vessel.

SailAndProp.com is the best place online to find all the information that you need to plan your future boating adventures. From choosing the best type of self steering gear to planning your route across the oceans, SailAndProp.com has got everything you need to hit the water with confidence. There’s no better way to keep up to date on all our latest boating info than to sign up to our newsletter, so don’t forget to subscribe today!

sailandprop

Recent Posts

Cruising While Working at Sea

It requires hard work, perseverance, the ability to adapt, and the willingness to take on a certain amount of (calculated) risk to run a remote business at sea.

Overcome the Challenges of Setting Sail

All first-time circumnavigators share certain challenges in the first few months of their voyage like anxiety, depression, seasickness, and problems at sea. The key is to overcome them and enjoy...

Wind Vane Self Steering: The Ultimate Guide

by Emma Sullivan | Jul 20, 2023 | Sailboat Gear and Equipment

Short answer: wind vane self steering

Wind vane self steering is a mechanical device used on sailboats to maintain a desired course without the need for continuous manual adjustment. It utilizes the force of the wind and a vertical axis to steer the boat by adjusting the position of the rudder.

How Wind Vane Self Steering Works: A Comprehensive Guide

Title: How Wind Vane Self-Steering Works: A Comprehensive Guide to Sailboat Autonomy

Introduction: Sailing is the epitome of freedom, embracing the unpredictable elements as we navigate vast oceans. However, when embarking on long journeys or overnight trips, the need for reliable self-steering systems arises. Enter wind vane self-steering! In this comprehensive guide, we will delve into this ingenious system, explaining its principles and mechanics while highlighting its benefits for seafaring enthusiasts. So hoist your sails and embark on a journey of knowledge as we unravel the inner workings of wind vane self-steering.

Chapter 1: The Basics of Wind Vane Self-Steering 1.1 Understanding Sailboats’ Balancing Act: – Explaining the importance of maintaining equilibrium between the sail and rudder configurations. – Highlighting challenges faced when manually helming during long passages.

1.2 Introduction to Wind Vanes: – Defining the wind vane as an autonomous steering mechanism driven by apparent wind direction. – Detailing their various components such as vanes, sensors, gears, and linkages.

Chapter 2: Principles Behind Wind Vanes 2.1 Apparent vs True Wind: – Unveiling the distinction between apparent and true wind direction. – Describing how wind vanes utilize apparent wind to adjust course.

2.2 Weight vs Force Systems: – Distinguishing weight-driven systems (servo pendulum) from force-driven ones (auxiliary rudder). – Discussing pros and cons of each system in different sailing conditions.

Chapter 3: Mechanics of Wind Vane Self-Steering 3.1 Servo Pendulum System: – Unveiling the engineering marvels behind servo pendulum systems. – Analyzing their interaction with changing winds and seas.

3.2 Auxiliary Rudder Systems: – Detailing the mechanism of auxiliary rudder systems, their hydrodynamics, and adjustability. – Discussing how they maintain sailboat course while minimizing yaw.

Chapter 4: Installation and Utilization Tips 4.1 Installing Wind Vanes on Different Sailboats: – Providing step-by-step instructions for mounting wind vanes. – Highlighting considerations for various boat designs and sizes.

4.2 Calibration and Fine-Tuning: – Elaborating on the importance of accurate calibration to ensure precise steering. – Offering pro tips to optimize performance under different sailing conditions.

Chapter 5: Advantages and Limitations 5.1 Benefits of Wind Vane Self-Steering: – Presenting the advantages of autonomy, reduced energy consumption, and enhanced safety during long-haul sailing trips.

5.2 Considerations in Complex Sailing Conditions: – Identifying limitations related to challenging weather patterns or narrow channels, necessitating manual intervention.

Conclusion – Navigating the Open Seas with Confidence: Wind vane self-steering systems revolutionize long-distance sailing by providing sailors with a reliable automated alternative to constant helming. Understanding the principles, mechanics, and installation tips outlined in this comprehensive guide will empower seafarers to navigate vast oceans with confidence, leaving them more time to revel in the beauty of their surroundings. Embrace the freedom that wind vane self-steering offers–the transformative companion for every true sailor!

Wind Vane Self Steering Explained: Step by Step Process

When it comes to sailing, one of the most essential tools for achieving steady and reliable course keeping is a wind vane self-steering system. This mechanism harnesses the power of the wind to effectively steer the vessel autonomously, ensuring sailors can enjoy a smoother and more hands-free sailing experience. In this blog post, we will delve into the step-by-step process of how wind vane self-steering works, unraveling its inner workings and highlighting its benefits.

Step 1: Understanding the Basics

Before we dive into the intricacies, let’s start with the fundamentals. A wind vane self-steering system consists of three main components: a wind vane, a linkage mechanism, and auxiliary steering gear. The wind vane acts as a sensory organ that detects changes in wind direction while transmitting these signals to the linkage mechanism. The linkage mechanism then translates those signals into appropriate movements, which are eventually transmitted to auxiliary steering gear responsible for adjusting sail trim or rudder angle.

Step 2: Wind Vane Sensitivity Adjustment

Once you’ve set up your wind vane self-steering system on board your yacht or sailboat, it’s crucial to fine-tune its sensitivity for optimal performance. By adjusting the weight distribution or adding counterweights to your wind vane, you can achieve precise responsiveness according to prevailing weather conditions. This careful calibration ensures that even subtle nuances in wind direction are accurately detected by the wind vane.

Step 3: Setting Course

Now that your system is finely tuned, it’s time to set your desired course manually using traditional methods such as compass bearings or GPS coordinates. Aligning your vessel towards this designated course provides initial guidance for your wind vane self-steerer.

Step 4: Autonomy Engaged

As soon as you activate your wind vane self-steering gear, you enable an autonomous sailor’s best friend. Once the wind vane starts detecting any deviations from your initial course, it sends signals to the linkage mechanism, instructing it to make corrections. This process ensures that your vessel automatically adjusts its heading to maintain the desired course against external factors such as wind shifts or gusts.

Step 5: Continuous Monitoring

While wind vane self-steering handles most course corrections independently, it does require regular monitoring to avoid any potential issues and make minor adjustments as needed. It is crucial to stay vigilant and keep an eye on how your self-steering system performs with changing wind conditions and other environmental factors.

Benefits of Wind Vane Self-Steering

Now that we’ve dived into the step-by-step process of wind vane self-steering, let’s explore its advantages:

1. Hands-free Sailing: With a properly calibrated and functioning wind vane self-steering system, sailors can free themselves from continuously holding the helm, affording a more relaxed sailing experience.

2. Increased Safety: Wind vane self-steering reduces fatigue in long ocean crossings by maintaining a steady course, minimizing human error risk at times when crew members might be physically exhausted.

3. Energy Efficiency: By utilizing the power of nature (the wind), a wind vane self-steerer requires no fuel consumption or electricity input for operation, making it an environmentally friendly and cost-effective solution for long-distance voyages.

In conclusion, the step-by-step process behind a wind vane self-steering system involves understanding the basics of its components, adjusting sensitivity levels, setting an initial course manually while enabling autonomy through continuous monitoring. This technology not only enhances safety but also allows sailors to enjoy hands-free sailing while embracing Mother Nature’s forces to keep their vessels on track efficiently. So why not embrace this clever innovation and sail away into effortless adventure?

Frequently Asked Questions about Wind Vane Self Steering

Frequently Asked Questions about Wind Vane Self Steering: Unlocking the Secrets to Effortless Sailing

If you’ve ever been on a sailing adventure or have spent any time around seasoned sailors, you’ve likely heard of wind vane self steering devices. These ingenious contraptions have sparked curiosity and interest among many sailing enthusiasts, but like any new concept, questions tend to arise. In this blog post, we will dive deep into the frequently asked questions surrounding wind vane self steering systems and shed light on their working principles. Get ready to unravel the science behind these mechanical marvels!

Q1: What exactly is a wind vane self-steering system?

A wind vane self-steering system is a mechanism designed to keep a sailing vessel on course without manual intervention from the helmsman. This device utilizes the power of the wind to maintain a steady heading even in challenging weather conditions. By harnessing wind pressure and utilizing specially shaped vanes, wind vane self-steering systems elegantly counterbalance forces acting on sails and rudders.

Q2: How does a wind vane self-steering system work?

The operation of a wind vane self-steering system revolves around one fundamental principle—using apparent wind angles and force to steer the boat. Typically mounted at the stern of a vessel, these systems consist of an arrow-shaped vane that reacts to changes in apparent wind direction. As the breeze shifts or fluctuates in intensity, subtle movements in the vane are transmitted via lines or linkage mechanisms to adjust the position of an auxiliary rudder at the boat’s stern.

When the boat begins deviating from its intended course due to shifting winds, turbulence, or waves, this auxiliary rudder automatically adjusts itself according to variations in apparent wind angles detected by the main vane. Consequently, as long as there is sufficient breeze available for propulsion, these systems effectively maintain precise navigation even during extended periods at sea. It’s like having an invisible helmsman tirelessly steering your vessel, allowing you to relax and enjoy the journey.

Q3: Are wind vane self-steering systems compatible with all types of boats?

Wind vane self-steering systems are highly versatile and can be installed on a wide range of sailboats. Whether you have a small, single-handed cruiser or a larger ocean-going yacht, there is likely a system that suits your vessel. The main considerations when choosing the right wind vane self-steering system for your boat include size, weight, balance, and how well it integrates with the existing rigging setup. Manufacturers provide detailed guidelines and support to ensure compatibility with various boat designs.

Q4: Can wind vane self-steering systems handle different weather conditions?

Absolutely! Wind vane self-steering systems are designed to thrive in diverse weather conditions and adapt to changing environments. Whether you’re facing calm seas or rough waters with strong winds, these remarkable devices remain stable and steadfast in their coursekeeping abilities. However, it is essential to learn about any limitations specific to the model you choose based on sailing experience and intended use.

Q5: Are wind vane self-steering systems difficult to install?

While installing a wind vane self-steering system may require some technical know-how, most reputable manufacturers provide comprehensive manuals and guidance materials tailored for DIY installations. However, if you prefer professional assistance or lack the confidence in setting it up yourself, seeking help from expert marine technicians is always an option worth considering.

In conclusion, wind vane self-steering systems offer sailors an unprecedented level of autonomy on their voyages by effortlessly maintaining course while they sit back and take in the panoramic beauty around them. Their ingenious working principles elegantly leverage wind power to navigate through uncharted waters. Embracing one of these marvels on your own sailing adventure might just be the key to unlocking new levels of sailing satisfaction. So, batten down the hatches, set your sails, and let the wind vane self-steering system be your faithful navigator on this extraordinary journey!

Mastering the Art of Wind Vane Self Steering: Tips and Techniques

For sailors navigating the vast blue oceans, wind vane self-steering systems are an invaluable tool. These impressive devices not only alleviate the stress of manual helm control but also empower sailors to sail solo or in small crews with ease. However, mastering the art of wind vane self-steering requires more than just installing the equipment – it demands practice, knowledge, and a cunning understanding of its intricacies. In this blog post, we will delve into the depths of wind vane self-steering, providing you with tips and techniques that will have you sailing like a seasoned pro.

Understanding the Basics:

To begin our journey towards mastering wind vane self-steering, let’s start by unraveling its fundamentals. A wind vane self-steering system essentially functions based on an aerodynamic principle: it utilizes changing winds to adjust your boat’s course automatically. The device consists of a wind vane mounted atop your vessel’s stern along with various lines and connections to your ship’s wheel or tiller.

1. Sail Trim is Key:

Properly adjusting your sails plays a crucial role in maximizing the efficiency of your wind vane self-steering system. Ideally, before engaging the device, ensure that your sails are appropriately trimmed for optimal performance based on existing weather conditions. Fine-tuning this aspect will allow for smoother operation and minimize any unnecessary strain on both boat and gear.

2. Get Acquainted with Your System:

Understanding how every component in your wind vane self-steering system works is vital for seamless operation. Familiarize yourself with all cables, lines, blocks, attaching points, and mechanical adjustments within your setup through careful study of instructions provided by manufacturers. Additionally, consider practicing installation and removal procedures before setting sail to save time during maintenance or repairs at sea.

3. Devise Efficient Linkages:

Connecting your wind vane to the ship’s wheel or tiller requires creating a linkage mechanism that transmits the vane’s signals accurately. Carefully select and adjust mechanical linkages, ensuring that they offer proper responsiveness and minimal play. Remember, any slack in these connections will decrease accuracy and compromise performance.

4. Experiment with Tension:

Fine-tuning the tension on your wind vane’s lines is essential for achieving optimal response. Experiment by adjusting the tension – both tightness and looseness – of these lines based on prevailing conditions such as wave heights, wind strength, course changes, or boat speeds. This flexibility allows you to adapt your wind vane self-steering system according to real-time situations and enhance its efficiency.

5. Observe Nature’s Cues:

Nature can be an exceptional teacher when it comes to utilizing wind vane self-steering systems effectively. Observing how wind shifts affect your vessel’s course during different weather patterns will help you develop a keen sense of understanding impending changes in wind direction. By balancing this observation with data from meteorological sources or barometers, you can anticipate shifts ahead of time, allowing for precise adjustments even before they happen.

6. Make Incremental Adjustments:

Once your wind vane self-steering system is activated, it is essential not to make abrupt adjustments unless absolutely necessary. Instead, opt for small incremental changes when altering course or sail trim. Gradual adaptations ensure smoother transitions without overwhelming the device with sudden demands.

7. Continuously Monitor Performance:

Constant vigilance is key while learning to master your wind vane self-steering system completely. Continuously monitor its performance by observing your boat’s behavior relative to sea conditions (weather helm, leeway). Appropriate awareness combined with timely tweaks ensures efficient operation throughout extended voyages.

8. Seek Expert Advice:

When seeking mastery over any subject matter, there is no substitute for expertise gained through experience and shared wisdom. Engage with sailing communities, forums, or seek advice from seasoned sailors who have honed their skills in wind vane self-steering. Their firsthand experiences and clever tricks will provide invaluable insights to propel your learning curve forward.

In conclusion, mastering the art of wind vane self-steering is a journey that requires practice, experimentation, and understanding. By grasping the basics, fine-tuning sail trim, learning your system inside-out, observing nature’s cues, and making incremental adjustments while monitoring performance attentively, you can unlock the true potential of this remarkable piece of sailing technology. So hoist your sails high and let the wind vane guide you towards a new realm of solo or small crew sailing prowess!

Choosing the Right Wind Vane Self Steering System for Your Boat

When it comes to sailing, there’s nothing quite like the feeling of gliding through the open waters, with the wind in your hair and the sun on your face. However, navigating a boat can be a challenging task, especially when you’re all alone out on the vast ocean. That’s where wind vane self steering systems come into play.

A wind vane self steering system is an invaluable piece of equipment that allows sailors to maintain course without having to constantly adjust their sails or helm. This automated system harnesses the power of the wind to steer the boat, freeing up valuable time and energy for sailors to focus on other important tasks.

But with so many different options available on the market, how do you choose the right wind vane self-steering system for your boat? Here are some key factors to consider:

1. Boat Size and Weight: The first thing you need to take into account is the size and weight of your boat. Wind vane self-steering systems come in various sizes designed to accommodate different vessels. It’s important to choose a system that is specifically built for boats within your size range to ensure optimal performance and stability.

2. Ease of Installation: As a sailor, you want a wind vane self-steering system that can be easily installed without requiring extensive modifications or additional support structures. Look for systems that come with clear installation instructions and minimal hardware requirements.

3. Weather Conditions: Sailors know that weather conditions can change rapidly at sea. Therefore, it’s essential to select a wind vane self-steering system that can handle a wide range of weather conditions – from light breezes to heavy winds and high seas. Look for systems that are durable and capable of maintaining control even in challenging weather scenarios.

4. Sensitivity Adjustment: Every boat handles differently based on its design and load distribution. To ensure precise control, choose a wind vane self-steering system that allows you to adjust its sensitivity to match your boat’s characteristics. This flexibility will enable you to fine-tune the system for optimal performance and responsiveness.

5. Reliability and Durability: When you’re out on the open water, you rely heavily on your equipment. Therefore, selecting a wind vane self-steering system from reputable manufacturers known for their reliability and durability is crucial. Look for systems made from high-quality materials that can withstand the harsh marine environment for years to come.

6. Cost: While cost should never be the sole determining factor, it’s still an important consideration when choosing a wind vane self-steering system for your boat. Evaluate different options and compare their features, performance, and price tags to find the best value for your money.

Now, armed with these essential considerations, you can embark on finding the perfect wind vane self-steering system that suits your boat and sailing needs. Remember to carefully research different products and consult with fellow sailors or experts if needed. With the right wind vane self-steering system onboard your boat, you’ll experience smoother sailing adventures like never before!

Troubleshooting Common Issues with Wind Vane Self Steering

Introduction:

Wind vane self-steering systems are a remarkable solution for sailors aiming to harness the power of the wind to navigate their vessels. By allowing the wind to guide the boat’s rudder, these systems reduce manual effort and provide a more reliable means of steering. However, like any piece of equipment, wind vane self-steering systems can sometimes encounter common issues that require troubleshooting. In this blog post, we will delve into some possible problems and provide professional, witty, and clever explanations on how to overcome them.

1. Lack of responsiveness: One frustrating issue that sailors may encounter with wind vane self-steering is a lack of responsiveness. If your system seems sluggish or fails to react promptly to changes in the wind direction, there are a few potential causes.

Explanation: Just like us humans after an indulgent Thanksgiving dinner, wind vanes can become lethargic too! The most common culprit for unresponsiveness is excessive friction within the system caused by wear or improper lubrication. To tackle this issue, start by giving your system a good inspection. Look for any signs of wear on bearings and joints while applying lubrication generously where needed (Think spa day for your wind vane). If this fails to resolve the problem, it might be worth checking if any foreign objects or debris have made their way into critical components – just imagine trying to navigate gingerly during peak pollen season!

2. Oscillations and instability: Unwanted oscillations or instability in your self-steering system can make sailing feel like riding a bucking bronco! This issue can be concerning and potentially dangerous if left unresolved.

Explanation: Imagine you are attempting to steer straight but your trusty wind vane has gained an affinity for dancing instead – quite embarrassing! The primary reason behind oscillations and instability is often an imbalance between sensitivity settings and sail trim (imagine mismatched dance partners). Adjusting both variables can help find the sweet spot. Additionally, thicker or heavier sails may contribute to excessive oscillations, so it might be time to reassess your sail wardrobe and consider adopting a lighter ensemble for smoother sailing (we all deserve a wardrobe makeover now and then!).

3. Misalignment and wandering: Has your wind vane suddenly decided to become an explorer, sailing in any direction other than the one you intended? Misalignment and wandering can occur due to various factors.

Explanation: Picture this – you want your wind vane pointing north, but instead, it decides it wants to discover hidden treasures in the opposite direction – quite the rebellious spirit! Misalignment is commonly caused by incorrect installation or loose connections between the wind vane and the boat’s rudder. Ensure that all parts are securely fastened with the precision of a complicated jigsaw puzzle (but without the frustration). When resolving misalignment issues, imagine you are showing your wind vane some tough love – tighten those nuts and bolts until they can’t even think about misbehaving!

Conclusion: While wind vane self-steering systems generally offer efficient steering solutions for sailors, encountering common issues is not uncommon. By understanding these challenges and implementing our witty troubleshooting advice, your wind vane will be back in shape in no time. Remember, a witty approach combined with professional expertise ensures smooth sailing both on water and through blog posts!

Recent Posts

- Sailboat Gear and Equipment

- Sailboat Lifestyle

- Sailboat Maintenance

- Sailboat Racing

- Sailboat Tips and Tricks

- Sailboat Types

- Sailing Adventures

- Sailing Destinations

- Sailing Safety

- Sailing Techniques

- --> Login or Sign Up

- Login or Sign Up -->

- B&B Annual Messabout

- Capsize Camp

- All Kayaks and Canoes

- Diva 15'8" Kayak

- Grand Diva 17'6" Kayak

- Moccasin 12' Canoe

- Flyfisher 13' Canoe

- Moccasin 14' Canoe

- Moccasin Double 15'6" Canoe

- Birder Decked Canoe 13' and 15'8

- Expedition Sailing Canoe

- All Dinghies and Tenders

- Catspaw Pram

- Spindrift Dinghy

- All Sailboats

- Core Sound 15

- Core Sound 17

- Core Sound 17 Mark 3

- Core Sound 20

- Core Sound 20 Mark 3

- Bay River Skiff 17

- Belhaven 19

- Mini Trimaran

- Class Globe 5.80 Kit

- Princess Sharpie 22'

- Princess Sharpie 26'

- All Powerboats

- All Jessy Skiffs 12-17'

- Jessy 12'

- Jessy 15'

- Jessy 17'

- All Outer Banks Cruisers

- Outer Banks 20

- Outer Banks 24

- Outer Banks 26

- All Ocracoke Center Consoles

- Ocracoke 20

- Ocracoke 20-B

- Ocracoke 24

- Ocracoke 256

- Cape Lookout 28

- All Other Kits and Plans

- Wing Foiling

- "Tractor" Canoe Seat

- Mast Head Floats

Windvane Self Steering

- All Building Supplies and Tools

- Marine Plywood

- All B&B Epoxy

- Temperature Control for Epoxy

- Epoxy Additives

- All Hardware and Rigging

- All Rigging

- Eyestraps and Fairleads

- Shackles, Hooks and Pins

- All Rudder Hardware

- Pintles and Gudgeons

- Tillers and Accessories

- Hardware kits

- All Masts, Track and More

- 6061-T6 Aluminum Tubing

- Sailtrack and Accessories

- Starboard Mast Plugs

- Wind indicators

- All Electrical

- Battery Monitors

- Solar Power System

- Boarding Ladders

- Beach Rollers

- All Apparel

- B&B Approved Products and Tools

Shop by Brand

B&b yacht designs.

- Amarine Made

- View all Brands

Shop by Category

- Rudder Hardware

- Other Kits and Plans

The purpose of a wind-vane self steering device is to allow the skipper to do something other than sitting at the helm. While this is not practical for most un-ballasted small sailboats, a self steering device is an essential tool for the cruising sailor. Graham has been testing the wind vane on his Core Sound 17 Mark 3 which has an excess of stability and is a perfect candidate for self steering. Following its success we have scaled up the mechanism which is built with modest tools and materials to work for larger boats up to 30 feet.

We are pleased to offer our wind vane design as a set of downloadable plans and instructional documents revealing all the dimensions and ratios used as well as recommended materials and construction methods for building this simple cheap and effective system at a fraction of the cost of an off the shelf system. Graham's design is based on his decades of experience building wind vane self steering gear since the 1970's and the tips and tricks for setting up a simple to build and reliable system are all conveyed here. The plans for our wind vane include full size templates for all the critical parts along with the dimensions and ratios used. A builder's guide covers recommended materials and things to watch out for as well as details of construction. All you have to do is adapt the system to work on your boats transom configuration. To learn more about our system and if it might be a good fit for you just keep reading.

How a self steering wind vane works. Short version. The “vane” part in the air provides the input to the rudder. The upper part of the system (the input or vane) is rotated such that it points into the apparent wind once the boat is on course. When the boat gets off course, the force of the wind hits the side of the vane causing it to lean over or in some cases rotate which in turn produces a correcting movement on the rudder. This turns the boat back on course until the vane is once again back to a neutral location. The trick to this is getting the right proportions, feedback and ratios of the vane, rudder, trim tab and control linkages.

Our Design Requirements

1. Low Friction : The name of the game is LOW FRICTION with wind vane self steering devices. We accomplish this with polished stainless steel against uhmw plastic for a cheap and reliable low friction connection.

2. Kick-up Auxiliary Rudder : This was a MUST HAVE for our shallow draft boats and not a feature we have seen on ANY other wind vane designs with an aux. rudder. The rudder pivots on a pin at the top of the transom and is held down with a line on a breakaway cleat.

3. Trim Tab Control : The aux. rudder is controlled by a trim tab that is actuated by the movement of the wind-vane (the part in the air). It's mesmerizing to watch and works completely without batteries or power.

4. Adjustable vane : The wind vane itself pivots on a horizontal axis that is inclined slightly. This creates an important damping effect in the actuation of the tab so that as the vane tilts it loses power because its projected area decreases. This reduces “hunting” and oversteering and unnecessary oscillation of the input to the rudder.

5. Removable vane : As with most systems, the vane is completely removed or replaced in seconds and can also be tilted back to increase the damping effect for high winds or made more vertical for light air which increases power. It can also be swapped out for a larger or smaller vane in lighter or stronger conditions.

6. Adjustable from anywhere in the cockpit : With the addition of a control wheel we can spin the upper part of the vane assembly 360 degrees using a control line routed around the cockpit. This means we can make small adjustments to the direction of the vane from anywhere you can reach the control line.

-Note that there are features we did not incorporate but may be important to some. One such feature is an emergency tiller. This allows for the use of the auxiliary rudder if the main rudder becomes inoperable. We would certainly want this feature on an ocean going cruising boat. If you build the auxiliary rudder up to reach the top of the transom then this is not difficult to do. Our kick up auxiliary rudder makes this a bit more of a challenge but a tiller tube can be fitted to reach a socket without much difficulty.

How does our wind vane system work...“I love it when you talk technical.” Our design uses a horizontal pivoting wind vane to control a trim tab on an auxiliary rudder. ( n this configuration, the vessels main rudder does the heavy lifting of keeping the boat generally on course essentially acting like a fixed skeg when the wind vane is engaged. The main rudder and most importantly the sails are adjusted first to balance the helm and then locked off with a tiller clutch. The auxiliary rudder then keeps the boat on course with small adjustments using a trim tab to amplify the power from the wind vane.

But will it work on my boat? … yes but! There are literally dozens of ways to control a boat using a wind vane. Here are a few put into a nice chart we found on one of the many commercially available wind vane self steering gear company websites. The most common systems are auxiliary rudder systems and servo pendulum systems. If you prefer a servo pendulum system or your boat is better suited for one then you can still use the vane assembly from these plans and simply adapt the lower unit however we do not show details for a pendulum in these plans. Servo pendulum gears can generate great power but they are not easy to build and come at a higher cost due to the stronger materials and complicated parts required. They also rely on additional lines and rigging running through the cockpit. We feel an auxiliary rudder or trim tab system offers the best all-around self-steering device for most boats especially for low cost and simple construction methods. A balanced auxiliary rudder can generate as much power as you need for most boats and has the benefit of being a redundant rudder in the event you need it. In addition, a super low power electronic autopilot like the pypilot can be connected directly to the trim tab or auxiliary rudder to steer a course while motoring for example.

We once installed an auxiliary rudder wind vane on a 45’ steel sloop one third of it’s way into a circumnavigation. It completed its way around the world even though the boat crashed onto a reef in Venezuela. The skipper shipped the auxiliary rudder while the boat pounded. After being dragged off the reef, and with the spade rudder inoperable, the aux rudder steered the boat to port where the main rudder and other damage was repaired. The owner said that the wind vane rudder which was equipped with an emergency tiller mount saved the boat.

The most cited disadvantage of an auxiliary rudder system are that they don't kick up and they require the construction and mounting of an extra rudder. Kicking up is an important feature and one we didn't want to give up especially for our smaller trailable boats. Our auxiliary rudder can be tilted completely out of the water when not in use. This is accomplished with some careful geometry and clever mounting BUT it is best suited for nearly vertical or forward raking transoms. You can still fit an auxiliary rudder to a transom with reverse rake but it is typically done with a very strong vertical tube bolted to the transom at the top and bottom with braces extending diagonally low to the waterline for support. This requires some complex geometry and custom mounting brackets so it is a bit more challenging to mount. If you are fitting a wind vane self steering system to a boat with an existing transom hung fixed (non kick up) rudder then a trim tab added directly to the main rudder may be a better solution for your boat and our wind vane would be easily adapted in this case.

The real challenge of mounting. “No size fits all.” Production self steering units will supply various kits and tubing and brackets to help make their systems fit your transom with just a few bolt holes carefully placed. Even with those systems it's up to you to mount it correctly and this will be no different. You will, without a doubt, need a custom mounting solution for your boat and you are the best person to design and build it! The system we are offering here is but a single example of a configuration fitted to a vertical or forward raking transom of our own design. We can’t help everyone mount this system to their individual transoms and there are probably some sterns that will really be challenging. You may need to design your own rudder for example using the parameters and ratios we offer in our plans as a guide in order to meet the needs of your transom configuration. This is for you to figure out! Remember, being a D.I.Y’er (also known as a sailor) is all about saving money by not charging yourself for the time it takes you to do stuff!

Limitations of a mechanical self steering device... What’s the “Ketch”? Wind vanes are not for everyone and one you build yourself has its own unique challenges to boot. A mechanical wind vane cannot blindly follow a compass course but instead must follow the ever-shifting wind direction and balance of the boat as wind and seat state change. On very fast boats, the apparent wind direction shifts so much that a wind vane is somewhere between useless and dangerous. Cruising cats can be fitted with wind vanes but typically an electronic autopilot is more practical due to their higher speeds. A mechanical wind vane relies on the wind speed being greater than the boat speed which for the vast majority of cruising boats is usually the case. On the current crop of large single handed around the world racers, automatic pilots have become so sophisticated they require training of the computer as they learn the boats behavior during high speed breakaways.

If you are travelling at displacement speeds with a bit of surfing thrown in and if you do not have unlimited power and money and if you do not mind making small adjustments to the boats trim and self-steering gear as the wind shifts, you will have a loyal assistant that never grows tired or needs feeding.

Staying in trim A good sailor keeps his boat in trim and a happy wind vane is one that is sailing a boat that is already balanced as well as possible. If your boat is heavy on the helm already then you may need the extra power provided by a servo pendulum system. If you have a hard time steering your boat, a wind vane (any wind vane) will too.

Space requirements Highlighted below on Graham's Core Sound 17 Mark 3 'Carlita'. Our design requires open space above the transom so it won't work on a standard Core Sound 17 for example due to the proximity of the mizzen sheets. The addition of a boomkin allows the mizzen sheet to be behind the reach of the wind vane sail in the case of the CS-17 Mk3. Likewise a yawl with long mizzen boom will be a challenge as the mechanism must be mounted far behind the transom.

A few notes from Graham....

"Horizontal axis vanes and servo pendulum paddles are the most powerful self steering systems and are certainly required for large or heavy handed vessels. Carlita is a light well mannered boat and requires finesse rather than brute force. If you have not already seen the self steering video, check out the video and answer your own question. She is running almost straight downwind and surfing. After this video was taken she surfed to a little over 10 knots without misbehaving."

Above, Graham steering his then unpainted Core Sound 17 Mark 3 Carlita with all sails flying in the 2016 Everglades Challenge. Note that this earlier version of the kick up wind vane employed a vertically pivoting vane which was converted the more recent version afterward. Vertically pivoting vanes have less power but do offer some advantages such as being able to just point into the wind when not in use. (photo Patrick Johnson)

Graham continues...

"The key is an ultra light vane and very low friction. The lead counter weight is just 6 oz on Carlita's system. to balance the vane. This makes the vane very responsive and reduces friction and lowers the mass moment of inertia. The next important feature is differential feedback in the linkage. This means that when the vane kicks the servo tab over and the tab turns the auxiliary rudder, the angle of the tab is rapidly reduced. If you do not have this feature the boat will hunt badly down wind where there is no natural balance from the sails as you do when close hauled. The whole thing is a delicate balance between power and feedback."

In the video below, Graham sails Carlita a Core Sound 17 Mark 3 with the wind vane rudder disabled and in the "raised" position and the boat steers herself with proper sail trim to windward. Notice that the tiller is simply lashed.

"I want the rudder fixed to aid directional stability. Before engaging the vane, I try to find the sweet spot for the rudder and lock it. I will then observe the course after the vane is engaged for a while and I may rotate the vane or move the tiller slightly. Usually I adjust the vane first. It is a powerful little vane and will tolerate a fair amount of imbalance. All self steering systems hunt but the better everything is balanced the less oversteering there will be.

If you do not enjoy fiddling then a wind vane may not be for you. Naturally they are worthless in waterways because the wind is too shifty. But It did do a great job last week running down the Cape Fear River. The GPS showed a top speed of 8.75 knots and the speed was rarely under 6, at least 3 knots of that was current." -Graham Byrnes

wavefront marine

Tiller clutch (standard).

B&B Windvane Self Steering Plans

Yachting Monthly

- Digital edition

Windvane steering: why it makes sense for coastal cruising

- Will Bruton

- October 15, 2018

No electricity needed, built for gale-force conditions and currently experiencing something of a renaissance amongst cruisers; windvane self-steering makes sense for coastal cruisers as much as offshore voyagers. Will Bruton took an in depth look at the options and how they work.

‘The distance run was 2,700 miles as the crow flies. During those 23 days I had not spent more than three hours at the helm. I just lashed the helm and let her go; whether the wind was abeam or dead aft, it was all the same: she always stayed on her course,’ wrote Joshua Slocum in 1895.

The ability of his long-keeled Spray to hold course without input from the helm was instrumental in making her the first yacht to circumnavigate single-handed.

Few modern boats bear these inherently balanced characteristics, so some form of autopilot is necessary to allow the skipper to rest.

Even for crewed passages, it can take an enormous strain off the crew without draining the battery. Some insurance companies even count windvane steering as an additional crew member, such is its contribution to life on board.

Unlike an electronic autopilot, self-steering needs no power

One solution experiencing something of a renaissance, is windvane self-steering.