- Club Finder

Enterprise Rigging Guide

Go To: Sailing - Rigging Guides

Posted on 19 July 2008 18:33

A very popular two handed boat, many of us may have started our sailing lives in an Enterprise, and many are bought and sold each year. With a strong class association and good racing circuit, Enterprises are a good boat to choose, particularly if you're not nimble enough for a faster Laser or RS double hander.

They're durable, very forgiving, undemanding, and fairly easy to repair. Either made from GRP (fibreglass) or wood, there are any Enterprises around, particularly on Ebay. If you've just bought one and don't know how to rig it, or are thinking of buying one, then read on.

Photo 1, The Enterprise

Photo 2, Seats and centreboard

While the Enterprise is a restricted design class, due to them being manufactured by a number of makers, over the last 55 years many different configurations of Enterprise have been built, some with built in bouyancy tanks, some with bouyancy bags instead, some with a sealed under foredeck, some without, some with transom flaps, others with just self-bailers. The differences also extend into the rigging; we will try to cover some of the differences in the article, but this is written for a fibreglass hull, with internal bouyancy tanks.

Photo 3, Toestrap adjusters

Photo 4, the Transom

Photo 5, Vernier adjusters on the shroud

Photo 6, the foredeck and mast step

Chances are if you buy an Enterprise, it won't be disassembled to the point of a Topper or Laser. For that reason, we aren't going to completely disassemble the boat and put absolutely everything together, for example the toestraps, and the mast. We will do a later article on how to raise (step) a mast; if you need assistance on this, pretty much anyone at your sailing club should be able to help.

Photo 7, the mast step and toestraps

Photo 8, one of two of the self-bailers,

Photo 9, The transom and traveller

Photo 10, The rudder pintles

Before we start, we'd just like to point out that in most Enterprises, you'll have two figure eight cleats for the halyards. We did originally in this one, until about a week before we did this, when someone (for once not us) decided to hoist a halyard with a little too much effort, and snapped off the top of one of the cleats.

What You Need

Mast, Spreads, Shroud, and Forestay (unless you've bought from new, these should all be together) Main Sail, Jib Sail Battens Main Sheet + Blocks, Jib Sheet Kicking strap/boom vang assembly + lines Outhaul Downhaul Boom Tiller + Tiller Extension, Rudder Painter Hull (bit obvious this one) + Centreboard Bungs (depending upon boat type).

Photo 11, all the ropes laid out on the rudder blade

Photo 12, the parts we need to rig the Enterprise

Please be aware that your boat may not come as class legal, unless you buy it new or off a serious racer. There is no one "legal" layout for an Enterprise; you need to get your boat "measured" and a measurement certificate drawn up if you plan to seriously race. Not all clubs require this; if you're sailing at a smaller club, then find out first whether you need to spend this money. The class association is a good place to start looking into this.

Lets Get Started!

Make sure you start with a clean boat, go all over it, and make sure nothing is broken, or if it is broken, make sure its' not important enough to stop you rigging the boat, or sailing it afterwards. Ensure you have all of the parts listed above if you need them; it's always a good idea to have a spares box with odds and ends of rope and fittings in. If you're like us, this may be several boxes, with more than a few odds and ends...

Photo 13, The forestay

There is a divided opinion on whether to rig boats on land or on the water - we'd suggest if it's not terribly windy, to rig the boat on land, hoist the jib, pointed head to wind, in anything other than a gentle breeze getting the mainsail ready, but hoisting it on the water. It's usual to start rigging the Enterprise front to back, starting with the jib.

As you can see on this example, the mast is already raised, with a length of rope securing the forestay to the bowplate on the front of the deck in Photo 13 (although a bottlescrew could be used instead), and the shrouds fitted to the shroudplates with "vernier" stay adjusters (Photo 5). These adjusters allow you to alter the angle of the mast forward and backward, known as the mast rake. The mast rake directly affects the centre of effort, and whether the boat will show (#) weather or (#) lee helm. The mast is stepped on the deck on this boat, with the mast step a separate piece of wood under the deck to the hull (Photo 6), which the kicking strap and toe straps are secured to (Photo 7).

Photo 14, clipping on the jib

Photo 15, Undoing a rope stopper

Open up and check your jib sail, and unroll it. Attach the tack (front corner) of the jib sail to the metal loop on the front of the deck (Photo 14), using a shackle - which type you use is not important, but it's best to use the smallest one possible (less weight). Attach the end of the halyard to the top of the jib sail using whichever fitting is necessary - on this example, it's a rope stopper. Make sure before you attach this to the sail there are no twists in the luff of the sail. Attach the stopper as shown, by making a bight in the rope, passing it through, then pass the stopper through the loop, and tighten (Photos 16-19).

Photo 16, Fixing a rope stopper

Photo 17, Fixing a rope stopper to a sail

Photo 18, Fixing a rope stopper to a sail

Photo 19, Fixing a rope stopper to a sail

To raise the jib, pull on the other end of the halyard (Photo 20). It should go up with very little resistance (other than any wind). Do not wrap the rope around your hand (Photo 21) - if you can't pull it up, bundle some slack rope in your hand for more grip, or get some plastic coated gloves.

Photo 20, Hoisting the jib

Photo 21, Never wrap the halyard rope around your hand

When the jib is fully raised, cleat it off around whichever fitting appropriate - in this case it's a figure 8 cleat. Take the rope around the outside of the cleat once (Photo 22), then figure 8 over the cleat once, then make a loop (Photo 23), with the working end becoming trapped underneath as you half-figure eight the rope around the cleat, as shown (Photo 24). This traps off the rope. Do not endlessly figure 8 the rope around the cleat - in an emergency this makes it difficult to uncleat quickly. Neatly bundle any remaining rope, and stow it over the top of the cleat, in a halyard back, or out of the way (Photo 25).

Photo 22, Figure 8 cleat the halyard

Photo 23, Form a loop

Photo 24, Lock off the halyard rope around the cleat

Photo 25, Tidy up the remaining rope

Next, if they are not already attached to the sail, tie on the jib sheets. FInd the middle piece of the rope, and tie a knot of some sort in it, either a double overhand knot as shown in the picture, or a stopper knot either side of the hole (which is less likely to cause the jib sheets to twist around each other). Ensure the jib sheets are not twisted then pass them through fairleed for the jib sheet jammers, inside the shrouds, and place a stopper knot or figure eight knot about 12 inches from the end of the rope (Photo 26). Make sure the jib sheets are not jammed off on land, as shown. If a gust comes, there is no freedom in the rope, and the boat could be taken off the trolley (Photo 27).

Photo 26, make sure the jib sheets aren't twisted

Photo 27, pass the jib sheets through the fairleads

If it's not already attached, then fix the main swivel block to the traveller on the transom of the boat. It should also have a becket on the top (Photo 30). It may not always look like the one in the picture - there are many variations of blocks made by many different manufacturers. The basic criteria for this one is to be big enough to take the mainsheet, with a swivel fitting at the base (so it will rotate around) and a becket at the top (which looks like a small fixed roller and is there to tie the end of the rope around). Next, fit the other block (which is just a plain pulley block with no becket or swivel base) to the underneath of the end of the boom (Photo 31).

Photo 30, Attach the lower mainblock

Photo 31, Attach the top mainblock

Now it's time to add the mainsheet. Tie one end around the becket on the bottom mainblock, using a bowline (Photo 32). Keep the knot as small as possible - if you make it too big, it will interfere with pulling the sail in tightly. Take the working (free) end, and pass it through the block on the underside of the boom, going through from the front to back (Photo 33), and then pass it down and through the lower block, from back to front (Photo 34). The working end then goes into the boat (Photo 35).

Photo 32, Bowline on the becket of the lower block

Photo 33, mainsheet through the upper block

Photo 34, mainsheet back through the lower block

Photo 35, mainsheet finished

Tie a stopper knot in the free end of the rope, to stop the rope end from passing through the pulley blocks - not something you want to have to fix on the water! To determine where a stopper knot should be put to limit the amount the mainsail can pull the boom out, wait until the sail is rigged, and pull the boom out sideways as far as it will go until just before it touches the shroud. Place a stopper knot in the rope here, and it will stop any damage to the shrouds during fast gybes.

The Main Sail

Unfold and spread the main sail out on a clear patch of ground. Check it over for any new holes or rips you may not have noticed before - this should be done every time you use it, because if you use an already damaged sail, you risk damaging it even more. Next, take the battens (stiff thin pieces of wood or plastic), figure out which fits in which pocket (the top one is usually smaller unless it's a full width or snap batten), and insert them as shown (Photo 37).

Photo 36, The business end of the outhaul

Photo 37, Insert the battens into the sail

Next. take the bottom back corner of the sail (the clew), and feed it into the front end of the boom (Photo 38), which should have a slot running along it's upper side. There may or may not be a plastic car (a little plastic object) on the bottom corner to feed into this track. On our boat we did not use the plastic car, because the sail was originally for a different boat. Pull the sail all the way through the boom track, until the front end reaches the front end of the boom, and secure it appropriately (in this case, with a split pin through holes in the boom and the sail as shown), as shown in Photo 39.

Photo 38, thread the sail into the boom

Photo 39, secure the front bottom corner of the sail

Next, attach the outhaul to the back end of the sail. Because this boom is slightly too large for the sail (actually we think the outhaul rope end shown has been shortened so the working end that clips onto the clew of the sail is too short), we took a rope from the sail to the shackle of the outhaul (Photo 40). This rope can be tied off in different ways, but if you run it around a couple of times, it becomes a makeshift 2:1 or 4:1 ratio system and you can pull the sail out easier (Photo 41).

Photo 40, attach the outhaul to the back bottom corner

Photo 41, tie it securely

If you don't have a pulley system, in many Enterprises the outhaul is just tied from the sail to a fixture on the end of the boom. This isn't ideal, as you cannot adjust the outhaul while sailing, and if you are serious about racing you will need to replace this. The outhaul on this boat can be seen in Photo 36.

Photo 42, Attach the halyard to the main sail

Photo 43, feed the mainsail head car up the mast slot

Now the main sail is ready to go up. Attach it to the end of the halyard (in this case using a stopper, Photo 42), and while one person feeds the luff of the mainsail into the mast track (Photo 43), the other should pull on the other end of the halyard to hoist it (Photo 44). Sails on older boats can be quite hard to hoist - if you are having any trouble hoisting the sail, make sure the mast track is free from any obstructions. Also make sure if there is a turning block at the bottom or top of the mast that it is well oiled and moves freely - this makes the sail pull up the mast much easier. A frayed luff can also make it difficult to hoist the sail.

Photo 44, Hoist the mainsail, use gloves if necessary

Photo 45, put the boom on the gooseneck

The final part of hoisting is the hardest. This Enterprise has an adjustable goose neck - if this is the case, then put the boom on the gooseneck, untighten it, and move it up as high as possible (Photo 45). Next, finish hoisting the sail to the top of the mast, cleat off the halyard as with the jib halyard (there will usually be a cleat for this), and then pull down on the boom and pull the gooseneck down, with it pulling the luff of the sail taut (Photo 46). This is much easier than putting the gooseneck in a lower position, and trying to pull the sail up the mast and make it taut this way. Tension the outhaul as necessary for wind conditions (Photo 47).

Photo 46, Lower the gooseneck and tighten the luff of the sail

Photo 47, Tighten the outhaul as necessary

A downhaul should be used as another sail control for the mainsail - this boat didn't have fittings for one, so we simply took a length of rope from points available and tied down the front corner of the mainsail (Photo 48). If there is not much wind when you plan to sail this may not be necessary. Once again, if you are serious about your sailing or racing, we're sure you'll replace this setup with something more appropriate.

Photo 48, attach the downhaul or cunningham

Photo 49, Assemble the kicking strap

Next, assemble the kicking strap/boom vang (Photo 49). Once again, there are many different configurations for this in an Enterprise, including various longer setups for single handed sailing. This one however is a simple 2:1 system with a single pulley block and a V-Jammer, assembled as shown. Fix the bottom end to the fitting in the bottom of the boat (in this case on the mast foot, Photo 50), and the top end fits into the fitting on the underside of the boom (Photo 51).

Photo 50, attach the kicker to the mast step

Photo 51, attach the other end to the boom

Photo 52, the assembled and installed kicking strap

Fit the rudder onto the pintles on the back of the boat (Photo 53). The rudder may come with two ropes - an uphaul and a downhaul. Slot the tiller extension into the top of the rudder, underneath the traveller, and secure the tiller to the rudder (in this case using a split pin). Feed the ropes for the uphaul and downhaul into the boat underneath the traveller, and attach onto the tiller where necessary (Photo 54).

Photo 53, The rudder attached and tiller inserted

Photo 54, the rudder uphaul rope secured

So there we have it, a fully rigged Enterprise. Because it's a restricted design rather than a one-design, there are different variations between boats, and we will add some pictures of these variations very soon!

Photo 55, The enterprise, fully rigged

Photo 56, The enterprise, fully rigged

Fig 1. Get all the gear ready

Home - About Us - Sailing - Club Finder - Links - Link To Us - Join Us - Contact Us - Classes - Reviews - Photo Galleries - Glossary - Knots

Disclaimer - Privacy Policy

The Worldwide Leader in Sailmaking

- Sail Care & Repair

- Sailing Gear

- Sail Finder

- Custom Sails

- One Design Sails

- Flying Sails

- New Sail Quote

- 3Di Technology

- Helix Technology

- Sail Design

- NPL RENEW Sustainable Sailcloth

- Sailcloth & Material Guide

- Polo Shirts

- Sweaters & Cardigans

- Sweatshirts & Hoodies

- Accessories

- Mid & Baselayers

- Deckwear & Footwear

- Luggage & Accessories

- Spring Summer '24

- Sailor Jackets

- Maserati X North Sails

- NS x Slowear

- Sailor Jacket

- Sustainability

- North Sails Blog

- Sail Like A Girl

- Icon Sailor Jacket

- Our Locations

- North SUP Boards

- North Foils

- North Kiteboarding

- North Windsurfing

SAIL FINDER

SAILING GEAR

COLLECTIONS & COLLAB

COLLECTIONS

WE ARE NORTH SAILS

ACTION SPORTS

Popular Search Terms

Collections

Sorry, no results for ""

ENTERPRISE TUNING GUIDE

This tuning guide has been prepared to help you get the most out of your North Sails as quickly as possible. It is meant as a starting point only, as we cannot cover all options and techniques. Feel free to modify and experiment in small steps to find what suits you best. If you find a settings that really work well, please keep us informed.

Mast Preparation

Ensure all sheaves are free running and the rigging is clean prior to stepping the mast.

Spreader Angle: Measure from spreader tip to tip.

Super Spar M2 Sleaved – 780 mm Proctor D+ – 760 mm

Spreader Length: Measure from spreader tip to wall of mast.

Super Spar M2 Sleaved – 410mm

Proctor D+ – 410mm

Rig Tension / Mast Rake

Rig tension is measured on the shrouds with a 3mm wire gauge. Mast rake is measured from top of mast to the centre of the transom. For sailing in all conditions the rig should be set up with Jib hoisted and tension fully on:

Rig Tension: 400lbs Mast Rake: 6470mm

This should make the mast straight with no Mainsail hoisted.

Ensure the Mainsail is fully hoisted – halyards do stretch.

Battens should be left in the sail at all times and whilst not afloat, the sail should be rolled down the leech, parallel to the battens.

This is used to position draft in the sail. Do not use any Cunningham until you become overpowered in heavy airs, then pull Cunningham on progressively harder as the breeze increases. This will move the draft of the sail forward in the top and de-power the upper leech.

Beating: In light and heavy airs the foot of the sail should be pulled tight. In medium airs, ease approximately 12mm.

Running: Keep the foot tight in all conditions.

Reaching: Ease fully in medium conditions, in light airs ease 25mm and in heavy airs pull out tight.

To find Jib lead position, follow the sheeting angle through the Jib clew. This should divide the Jib luff approximately in half. When sailing upwind in a Force 3, all the tell tales should break together. In medium/heavy airs, the Jib should be sheeted hard to maximise pointing ability.

In lighter conditions the Jib sheet needs to be eased approximately 12mm to keep the top of the leech open. Once a fairlead position has been found, use it in all conditions with very heavy airs, then move back 25mm. This will flatten the base of the Jib and open the leech, keeping the boat driving and on her feet.

Good luck on the water!

Featured stories, pursuing perfection: tom gillard and the one design team, a visionary sail designer | gautier sergent (1977-2024), how to care for your foul weather gear.

- Refresh page

- Plan Your Visit

- Plan Your Trip

- Group Tours

- Research Center & Archives

- Educational Programs

- Bibliography

- Related Links

- Events Calendar

- The Heritage Museum Plan

- Book A Historic Property

- Governance Resources

- Press Releases

- NISHM in the News

- Sponsorship

In 1929 Sir Thomas Lipton issued a challenge to the Americans for the America's Cup. It was his fifth challenge and signified a whole new era in design evolution and racing. The late 1920s and 1930s also heralded the beginning of an age when yachts from both sides of the Atlantic were being raced under the same rule — the American Universal Rule. Previously, British yachts had raced under the International Rule, a rule that gave an advantage to bermudan rigged yachts, but which was restrictive for boats bigger than 48ft (141—2m). The Americans wanted to race bigger boats and so introduced the Universal Rule. It was based on ideas proposed by Nat Herreshoff and meant waterline length could be increased without sail area being restricted, as it had been under the International Rule. This was compensated by a larger displacement and draught was limited to 15ft (4.6m). The J-Class were the foremost designs under this rule.

Under the International Rule, yachts were very similar in specification, but under the Universal Rule they differed considerably. Several existing yachts, Astra, Candida, White Heather II and Britannia , were converted to comply with the rule and raced alongside the Js. They cannot, however, be classed as true Js. Of the true J-Class, only ten were ever built and these raced together for just eight seasons from 1930 to 1937. The rules for the J-Class stipulated that length overall had to exceed 120ft; LWL had to be between 79 and 87ft (36.6 x 24-26.5m) and they could displace up to 160 tons.

In answer to Lipton's challenge of 1929 the Americans designed four J-Class yachts as possible defenders. Enterprise, Whirlwind, Yankee and Weetamoe were launched within a month of each other; Weetamoe and Enterprise from the Herreshoff yard and Yankee and Whirlwind from Lawley & Son's yard in Bristol.

Enterprise was the first launched on 14 April 1930 and was later chosen as the Cup defender. At 80ft (24.4m) LWL she was shortest of the four US Js and conventional in all aspects. Designed by W Starling Burgess, she had lightweight rigging and was the fastest of the four to windward in moderate airs.

Whirlwind , the second J launched 16 days later, was the most revolutionary of the four. Francis L Herreshoff had moved away from conventional yachts and designed a boat which took the new rule to its extremes. Whirlwind combined many new ideas and Herreshoff experimented with hull shape and rig. She was the longest of the early Js at 86ft (26m) on the waterline and remained so until Ranger and Endeavour II were built in 1937. She was built of semi-composite construction (the other three American Js were built out of the highly expensive tobin bronze), was double-ended and had a permanent backstay. Uffa Fox described her profile as: "Very pleasing to the eye, the stem sweeping down to the keel in a very sweet line, and to a man who, like myself, believes that a pointed stern is a logical ending for all vessels, her stern is a joy to behold." He predicted "If the Yacht Racing Rules govern well and wisely, we shall see Whirlwind racing 50 years hence. If they do not she will probably be cruising then." But Whirlwind met an early demise. Her building was delayed as she didn't meet Lloyd's A1 scantling rules and she wasn't chosen to be the 1930s defender. She was often out-performed when close hauled, her steering gear making her difficult to steer. She was eventually scrapped along with Enterprise in 1935. However, her unusual double headsail rig was later adopted by the rest of the Js.

The third American J, Yankee , was the best all-rounder. At 84ft on the waterline and 125ft (25.6 x 38m) length overall, she was solidly made of tobin bronze and was extremely well balanced. Designed by Frank Paine, Yankee had an almost straight sheerline and easy lines. She was a powerful contender for defender, but not fine tuned enough to succeed. She did, however, take part in the 1934 America's Cup trials and with alterations to her rig, to carry more sail, and bow, which was lengthened and made more of a V-shape, she then proved more successful, especially in light winds.

Of the American Js, Yankee was the only one to sail in British waters when she was bought by Gerald Lambert and crossed the Atlantic in 1935. She was scrapped in 1941.

The fourth of the American Js was Weetamoe , which was designed by Clinton Crane and was the narrowest of the early four. Despite claims that Yankee was the best all-rounder, Weetamoe is said to have been the closest rival to Enterprise to be the Cup defender. Charles Nedwick, in Ian Dear's book Enterprise to Endeavour, describes Weetamoe as having a profile "that is practically a triangle, with a straight line from the after end of the waterline to the bottom of the keel and thence a line which is slightly convex, and then slightly concave to the forward end of the waterline." In an attempt to better performance and make her less tender, her profile below the water was radically altered in 1934 with a new contour and bulb keel. The alterations failed and not long afterwards were reversed. In common with the other Js, she had about 43ft (13m) of overhang and her hull, Nicholson opined, "was the best of all the US Js".

1930 In August Enterprise qualified for the America’s Cup racing off Mattapoisett Massachusetts by defeating rival yachts Yankee , Whirlwind and Weetamoe .

The Americans had a distinct advantage over Britain in the 1930 America's Cup. They had the money to build four Js over Britain's one, yet Shamrock V was a hot contender. She was designed by Nicholson and built at the family yard in 1930, and before she crossed the Atlantic to attend the Cup she had notched up more than 700 sea miles (1,296km), won 15 out of the 22 races she had entered and had been tweaked and tested to a high degree. When Shamrock V and Enterprise eventually met off Newport, Rhode Island, later that year, the two Js were well matched in hull profile, but differed significantly in rig. Enterprise's rigging was lighter, she had the Park Avenue boom, which was so advantageous to windward, and had lots of winches on board. Shamrock V meanwhile, was under-winched and hard work to sail. She has since, however, proved her success in that she is still sailing today.

Enterprise , winner of the 14th America’s Cup, in 1930, crushing Shamrock 4-0.

Just after the America's Cup races, Enterprise was dry-docked. It would never sail again.

1935 Broken up for scrap.

Source:www.classicboat.co.uk 7/2/2007

Cup(s) Sailed: 1930 (won)

Crew: 31

Owners: Winthrop W. Aldrich, Harold S. Vanderbilt, and Vincent Astor

Year Built: 1930

Launched: April 14, 1930

Type: Keel Sloop, fitted with two centerboards

Designer: William Starling Burgess

Builder: Herreshoff Manufacturing Company

Construction

Frames: Steel

Planking Top: Steel — Supplied by Lukens

Planking Bottom: Tobin Bronze

Mast: Aluminum

Spinnaker Pole: Wood

Keel Ballast: Lead

Length Overall: 119.7 ft. / 36.49 m

Length Waterline: 80.0 ft. / 24.38 m

Beam: 22.1 ft. / 6.73 m

Draft: 14.5 ft. / 4.42 m

Draft with Keel Lowered: N/A

Displacement: 127.6 tons

Tonnage: N⁄A

Sail Area: 2,311.5 sq. ft. / 704.48 sq. m

Mast: 150.8 ft. / 45.97 m

Boom: 78.8 ft. / 24.01 m

Bowsprit: N/A

Top Mast: N/A

Source:www.americascup.com 7/2/2007

Guide to Understanding Sail Rig Types (with Pictures)

There are a lot of different sail rig types and it can be difficult to remember what's what. So I've come up with a system. Let me explain it in this article.

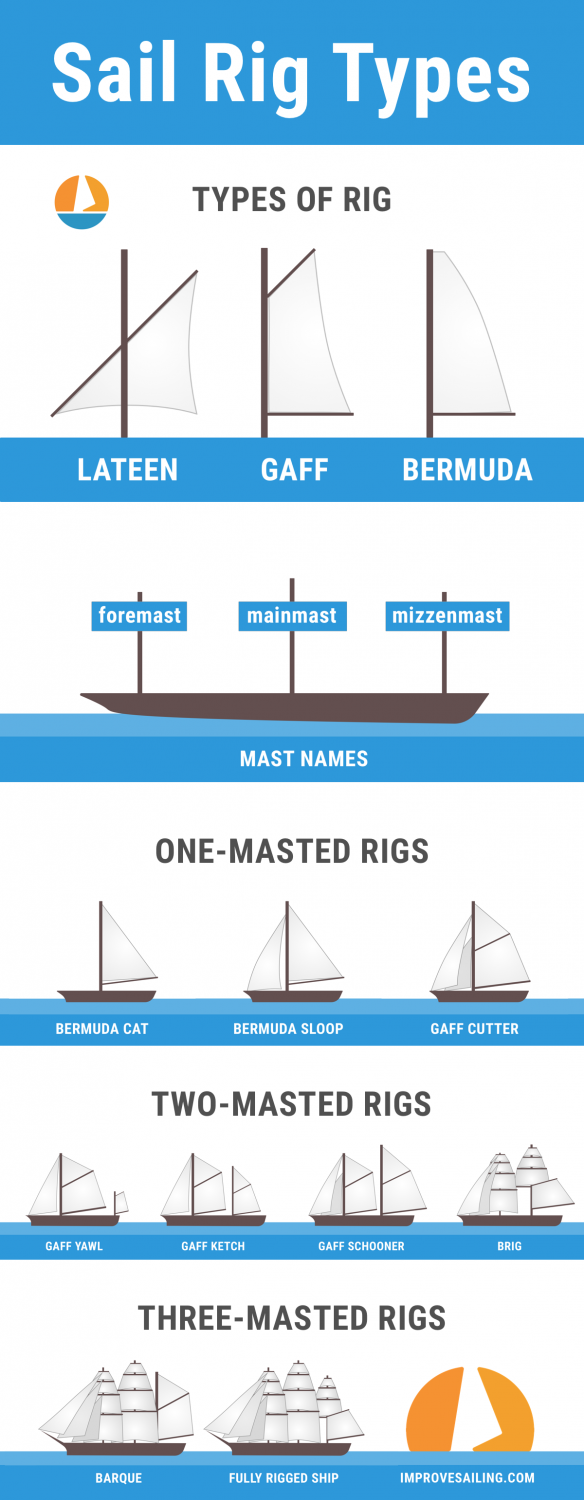

What are the different types of sail rig? The sail rig is determined by the number of masts and the layout and shape of sails. Most modern ships are fore-and-aft rigged, while old ships are square-rigged. Rigs with one mast are sloops and cutters. Ketches, yawls, brigs, and schooners have two masts. Barques have three masts. Rigs can contain up to seven masts.

'Yeah, that's a gaff brig, and that a Bermuda cutter' - If you don't know what this means (neither did I) and want to know what to call a two-masted ship with a square-rigged mainsail, this article is definitely for you.

On this page:

More info on sail rig types, mast configurations and rig types, rigs with one mast, rigs with two masts, rigs with three masts, related questions.

This article is part 2 of my series on sails and rig types. Part 1 is all about the different types of sails. If you want to know everything there is to know about sails once and for all, I really recommend you read it. It gives a good overview of sail types and is easy to understand.

The Ultimate Guide to Sail Types and Rigs (with Pictures)

First of all, what is a sail rig? A sail rig is the way in which the sails are attached to the mast(s). In other words, it's the setup or configuration of the sailboat. The rig consists of the sail and mast hardware. The sail rig and sail type are both part of the sail plan. We usually use the sail rig type to refer to the type of boat.

Let's start by taking a look at the most commonly used modern sail rigs. Don't worry if you don't exactly understand what's going on. At the end of this article, you'll understand everything about rig types.

The sail rig and sail plan are often used interchangeably. When we talk of the sail rig we usually mean the sail plan . Although they are not quite the same. A sail plan is the set of drawings by the naval architect that shows the different combinations of sails and how they are set up for different weather conditions. For example a light air sail plan, storm sail plan, and the working sail plan (which is used most of the time).

So let's take a look at the three things that make up the sail plan.

The 3 things that make up the sail plan

I want to do a quick recap of my previous article. A sail plan is made up of:

- Mast configuration - refers to the number of masts and where they are placed

- Sail type - refers to the sail shape and functionality

- Rig type - refers to the way these sails are set up on your boat

I'll explore the most common rig types in detail later in this post. I've also added pictures to learn to recognize them more easily. ( Click here to skip to the section with pictures ).

How to recognize the sail plan?

So how do you know what kind of boat you're dealing with? If you want to determine what the rig type of a boat is, you need to look at these three things:

- Check the number of masts, and how they are set up.

- You look at the type of sails used (the shape of the sails, how many there are, and what functionality they have).

- And you have to determine the rig type, which means the way the sails are set up.

Below I'll explain each of these factors in more detail.

The most common rig types on sailboats

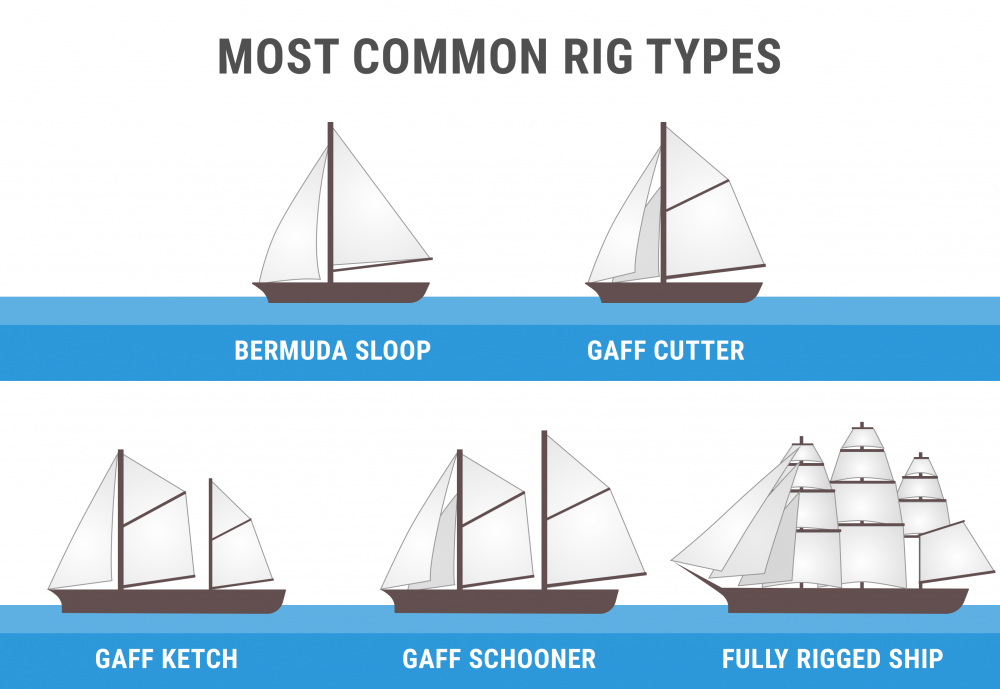

To give you an idea of the most-used sail rigs, I'll quickly summarize some sail plans below and mention the three things that make up their sail plan.

- Bermuda sloop - one mast, one mainsail, one headsail, fore-and-aft rigged

- Gaff cutter - one mast, one mainsail, two staysails, fore-and-aft rigged

- Gaff schooner - two-masted (foremast), two mainsails, staysails, fore-and-aft rigged

- Gaff ketch - two-masted (mizzen), two mainsails, staysails, fore-and-aft rigged

- Full-rigged ship or tall ship - three or more masts, mainsail on each mast, staysails, square-rigged

The first word is the shape and rigging of the mainsail. So this is the way the sail is attached to the mast. I'll go into this later on. The second word refers to the mast setup and amount of sails used.

Most sailboats are Bermuda sloops. Gaff-rigged sails are mostly found on older, classic boats. Square-rigged sails are generally not used anymore.

But first I want to discuss the three factors that make up the sail plan in more detail.

Ways to rig sails

There are basically two ways to rig sails:

- From side to side, called Square-rigged sails - the classic pirate sails

- From front to back, called Fore-and-aft rigged sails - the modern sail rig

Almost all boats are fore-and-aft rigged nowadays.

Square sails are good for running downwind, but they're pretty useless when you're on an upwind tack. These sails were used on Viking longships, for example. Their boats were quicker downwind than the boats with fore-and-aft rigged sails, but they didn't handle as well.

The Arabs first used fore-and-aft rigged sails, making them quicker in difficult wind conditions.

Quick recap from part 1: the reason most boats are fore-and-aft rigged today is the increased maneuverability of this configuration. A square-rigged ship is only good for downwind runs, but a fore-and-aft rigged ship can sail close to the wind, using the lift to move forward.

The way the sails are attached to the mast determines the shape of the sail. The square-rigged sails are always attached the same way to the mast. The fore-and-aft rig, however, has a lot of variations.

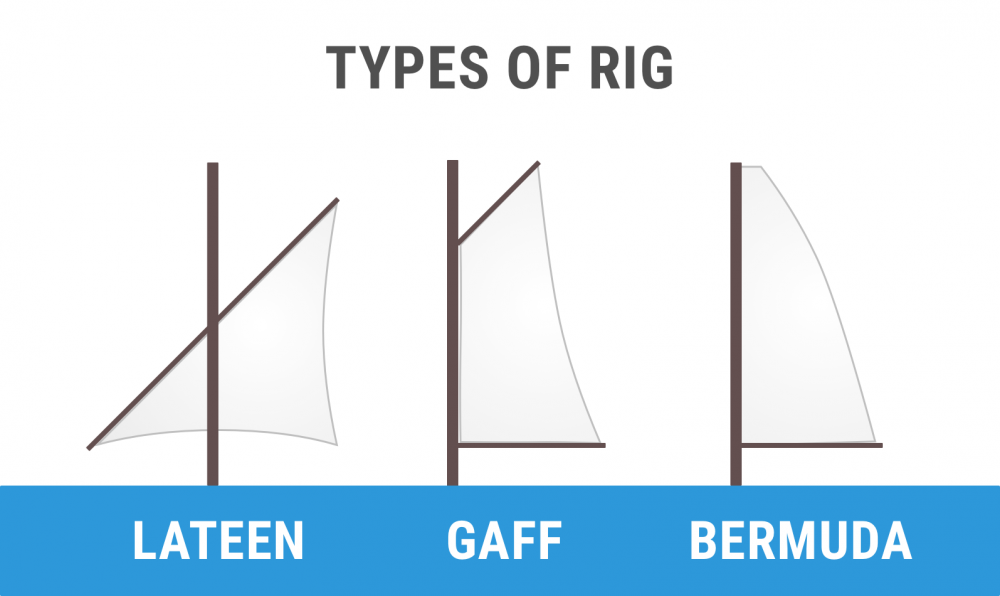

The three main sail rigs are:

- Bermuda rig - most used - has a three-sided (triangular) mainsail

- Gaff rig - has a four-sided mainsail, the head of the mainsail is guided by a gaff

- Lateen rig - has a three-sided (triangular) mainsail on a long yard

The Bermuda is the most used, the gaff is a bit old-fashioned, and the lateen rig is outdated (about a thousand years). Lateen rigs were used by the Moors. The Bermuda rig is actually based on the Lateen rig (the Dutch got inspired by the Moors).

Other rig types that are not very common anymore are:

- Junk rig - has horizontal battens to control the sail

- Settee rig - Lateen with the front corner cut off

- Crabclaw rig

Mast configuration

Okay, we know the shape of the mainsail. Now it's time to take a look at the mast configuration. The first thing is the number of masts:

- one-masted boats

- two-masted boats

- three-masted boats

- four masts or up

- full or ship-rigged boats - also called 'ships' or 'tall ships'

I've briefly mentioned the one and two mast configurations in part 1 of this article. In this part, I'll also go over the three-masted configurations, and the tall ships as well.

A boat with one mast has a straightforward configuration because there's just one mast. You can choose to carry more sails or less, but that's about it.

A boat with two masts or more gets interesting. When you add a mast, it means you have to decide where to put the extra mast: in front, or in back of the mainmast. You can also choose whether or not the extra mast will carry an extra mainsail. The placement and size of the extra mast are important in determining what kind of boat we're dealing with. So you start by locating the largest mast, which is always the mainmast.

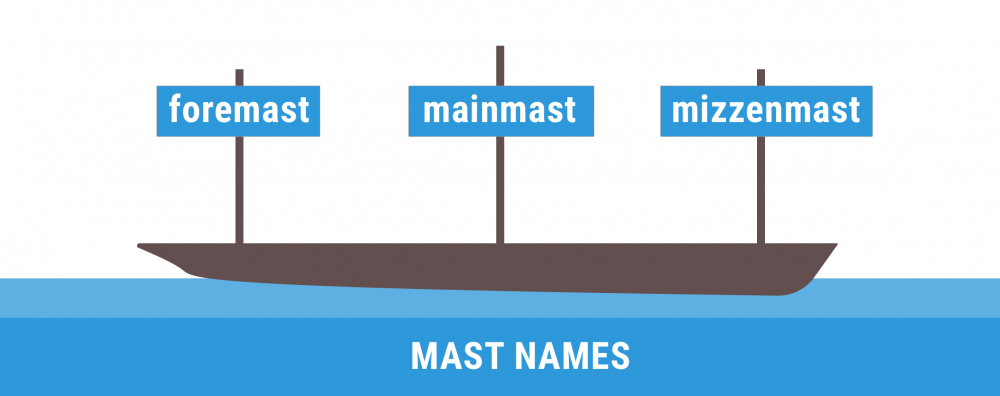

From front to back: the first mast is called the foremast. The middle mast is called the mainmast. And the rear mast is called the mizzenmast.

What is the mizzenmast? The mizzenmast is the aft-most (rear) mast on a sailboat with three or more masts or the mast behind the mainmast on a boat with two masts. The mizzenmast carries the mizzen sail. On a two-masted boat, the mizzenmast is always (slightly) smaller than the mainmast. What is the purpose of the mizzen sail? The mizzen sail provides more sail area and flexibility in sail plan. It can be used as a big wind rudder, helping the sailor to have more control over the stern of the ship. It pushes the stern away from the wind and forces the bow in the opposite way. This may help to bring the bow into the wind when at anchor.

I always look at the number of masts first, because this is the easiest to spot. So to make this stuff more easy to understand, I've divided up the rig types based on the number of masts below.

Why would you want more masts and sail anyways?

Good question. The biggest advantage of two masts compared to one (let's say a ketch compared to a sloop), is that it allows you to use multiple smaller sails to get the same sail area. It also allows for shorter masts.

This means you reduce the stress on the rigging and the masts, which makes the ketch rig safer and less prone to wear and tear. It also doesn't capsize as quickly. So there are a couple of real advantages of a ketch rig over a sloop rig.

In the case of one mast, we look at the number of sails it carries.

Boats with one mast can have either one sail, two sails, or three or more sails.

Most single-masted boats are sloops, which means one mast with two sails (mainsail + headsail). The extra sail increases maneuverability. The mainsail gives you control over the stern, while the headsail gives you control over the bow.

Sailor tip: you steer a boat using its sails, not using its rudder.

The one-masted rigs are:

- Cat - one mast, one sail

- Sloop - one mast, two sails

- Cutter - one mast, three or more sails

The cat is the simplest sail plan and has one mast with one sail. It's easy to handle alone, so it's very popular as a fishing boat. Most (very) small sailboats are catboats, like the Sunfish, and many Laser varieties. But it has a limited sail area and doesn't give you the control and options you have with more sails.

The most common sail plan is the sloop. It has one mast and two sails: the main and headsail. Most sloops have a Bermuda mainsail. It's one of the best racing rigs because it's able to sail very close to the wind (also called 'weatherly'). It's one of the fastest rig types for upwind sailing.

It's a simple sail plan that allows for high performance, and you can sail it short-handed. That's why most sailboats you see today are (Bermuda) sloops.

This rig is also called the Marconi rig, and it was developed by a Dutch Bermudian (or a Bermudian Dutchman) - someone from Holland who lived on Bermuda.

A cutter has three or more sails. Usually, the sail plan looks a lot like the sloop, but it has three headsails instead of one. Naval cutters can carry up to 6 sails.

Cutters have larger sail area, so they are better in light air. The partition of the sail area into more smaller sails give you more control in heavier winds as well. Cutters are considered better for bluewater sailing than sloops (although sloops will do fine also). But the additional sails just give you a bit more to play with.

Two-masted boats can have an extra mast in front or behind the mainmast. If the extra mast is behind (aft of) the mainmast, it's called a mizzenmast . If it's in front of the mainmast, it's called a foremast .

If you look at a boat with two masts and it has a foremast, it's most likely either a schooner or a brig. It's easy to recognize a foremast: the foremast is smaller than the aft mast.

If the aft mast is smaller than the front mast, it is a sail plan with a mizzenmast. That means the extra mast has been placed at the back of the boat. In this case, the front mast isn't the foremast, but the mainmast. Boats with two masts that have a mizzenmast are most likely a yawl or ketch.

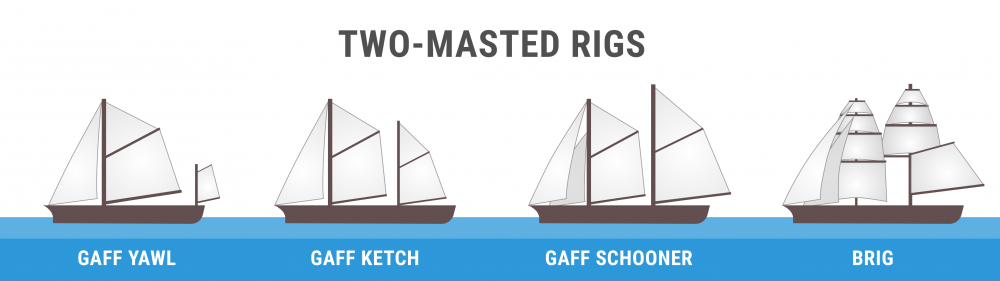

The two-masted rigs are:

- Lugger - two masts (mizzen), with lugsail (a cross between gaff rig and lateen rig) on both masts

- Yawl - two masts (mizzen), fore-and-aft rigged on both masts. Main mast is much taller than mizzen. Mizzen without a mainsail.

- Ketch - two masts (mizzen), fore-and-aft rigged on both masts. Main mast with only slightly smaller mizzen. Mizzen has mainsail.

- Schooner - two masts (foremast), generally gaff rig on both masts. Main mast with only slightly smaller foremast. Sometimes build with three masts, up to seven in the age of sail.

- Bilander - two masts (foremast). Has a lateen-rigged mainsail and square-rigged sails on the foremast and topsails.

- Brig - two masts (foremast), partially square-rigged. The main mast carries small lateen-rigged sail.

The yawl has two masts that are fore-and-aft rigged and a mizzenmast. The mizzenmast is much shorter than the mainmast, and it doesn't carry a mainsail. The mizzenmast is located aft of the rudder and is mainly used to increase helm balance.

A ketch has two masts that are fore-and-aft rigged. The extra mast is a mizzenmast. It's nearly as tall as the mainmast and carries a mainsail. Usually, the mainsails of the ketch are gaff-rigged, but there are Bermuda-rigged ketches too. The mizzenmast is located in front of the rudder instead of aft, as on the yawl.

The function of the ketch's mizzen sail is different from that of the yawl. It's actually used to drive the boat forward, and the mizzen sail, together with the headsail, are sufficient to sail the ketch. The mizzen sail on a yawl can't really drive the boat forward.

Schooners have two masts that are fore-and-aft rigged. The extra mast is a foremast which is generally smaller than the mainmast, but it does carry a mainsail. Schooners are also built with a lot more masts, up to seven (not anymore). The schooner's mainsails are generally gaff-rigged.

The schooner is easy to sail but not very fast. It handles easier than a sloop, except for upwind, and it's only because of better technology that sloops are now more popular than the schooner.

The brig has two masts. The foremast is always square-rigged. The mainmast can be square-rigged or is partially square-rigged. Some brigs carry a lateen mainsail on the mainmast, with square-rigged topsails.

Some variations on the brig are:

Brigantine - two masts (foremast), partially square-rigged. Mainmast carries no square-rigged mainsail.

Hermaphrodite brig - also called half brig or schooner brig. Has two masts (foremast), partially square-rigged. Mainmast carries a gaff rig mainsail and topsail, making it half schooner.

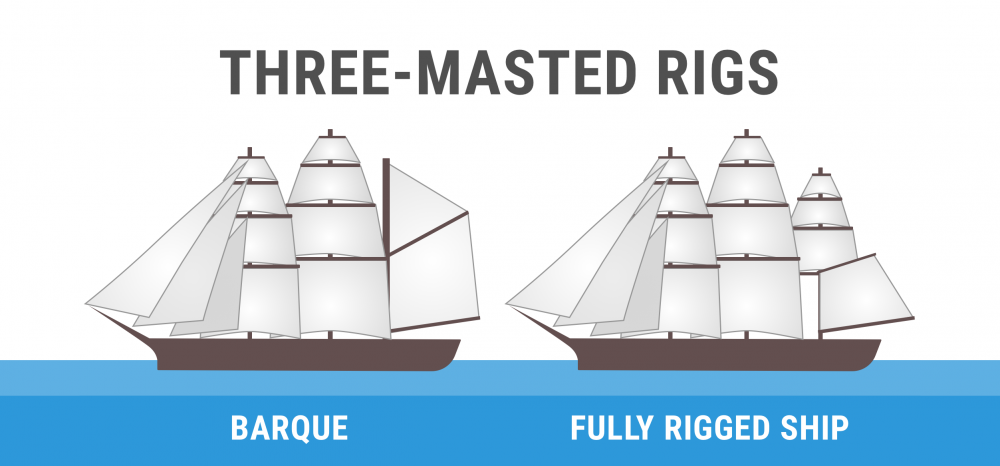

Three-masted boats are mostly barques or schooners. Sometimes sail plans with two masts are used with more masts.

The three-masted rigs are:

- Barque - three masts, fore, and mainmast are square-rigged, the mizzenmast is usually gaff-rigged. All masts carry mainsail.

- Barquentine - three masts, foremast is square-rigged, the main and mizzenmast are fore-and-aft rigged. Also called the schooner barque.

- Polacca - three masts, foremast is square-rigged, the main and mizzenmast are lateen-rigged.

- Xebec - three masts, all masts are lateen-rigged.

A barque has three or four masts. The fore and mainmast are square-rigged, and the mizzen fore-and-aft, usually gaff-rigged. Carries a mainsail on each mast, but the mainsail shape differs per mast (square or gaff). Barques were built with up to five masts. Four-masted barques were quite common.

Barques were a good alternative to full-rigged ships because they require a lot fewer sailors. But they were also slower. Very popular rig for ocean crossings, so a great rig for merchants who travel long distances and don't want 30 - 50 sailors to run their ship.

Barquentine

The barquentine usually has three masts. The foremast is square-rigged and the main and mizzenmast fore-and-aft. The rear masts are usually gaff-rigged.

Faster than a barque or a schooner, but the performance is worse than both.

The polacca or polacre rig has three masts with a square-rigged foremast. The main and mizzenmast are lateen-rigged. Beautiful boat to see. Polacca literally means 'Polish' (it's Italian). It was a popular rig type in the Mediterranean in the 17th century. It looks like the xebec, which has three lateen-rigged masts.

Fun fact: polaccas were used by a Dutch sailor-turned-Turkish-pirate (called Murat Reis).

The xebec is a Mediterranean trading ship with three masts. All masts are lateen-rigged. I couldn't find any surviving xebecs, only models and paintings. So I guess this rig is outdated a long time.

A boat with three or more masts that all carry square-rigged sails is called a ship, a tall ship, or a full-rigged ship. So it's at this point that we start calling boats 'ships'. It has nothing to do with size but with the type of rigging.

More sails mean less stress on all of them. These ships use a lot of sails to distribute the forces, which reduces the stress on the rigging and the masts. Square sails mean double the sail area in comparison to triangular sails.

They are quite fast for their size, and they could outrun most sloops and schooners (schooners were relatively a lot heavier). The reason is that tall ships could be a lot longer than sloops, giving them a lot of extra hull speed. Sloops couldn't be as large because there weren't strong enough materials available. Try making a single triangular sail with a sail area of over 500 sq. ft. from linen.

So a lot of smaller sails made sense. You could have a large ship with a good maximum hull speed, without your sails ripping apart with every gust of wind.

But you need A LOT of sailors to sail a tall ship: about 30 sailors in total to ie. reef down sails and operate the ship. That's really a lot.

Tall ships are used nowadays for racing, with the popular tall ship races traveling the world. Every four years I go and check them out when they are at Harlingen (which is very close to where I live).

Check out the amazing ships in this video of the tall ship races last year near my hometown. (The event was organized by friends of mine).

What is the difference between a schooner and a sloop? A schooner has two masts, whereas the sloop only has one. The schooner carries more sails, with a mainsail on both masts. Also, sloops are usually Bermuda-rigged, whereas schooners are usually gaff-rigged. Most schooners also carry one or two additional headsails, in contrast to the single jib of the sloop.

What do you call a two-masted sailboat? A two-masted sailboat is most likely a yawl, ketch, schooner, or brig. To determine which one it is you have to locate the mainmast (the tallest). At the rear: schooner or brig. In front: yawl or ketch. Brigs have a square-rigged foremast, schooners don't. Ketches carry a mainsail on the rear mast; yawls don't.

What is a sloop rig? A sloop rig is a sailboat with one mast and two sails: a mainsail and headsail. It's a simple sail plan that handles well and offers good upwind performance. The sloop rig can be sailed shorthanded and is able to sail very close to the wind, making it very popular. Most recreational sailboats use a sloop rig.

What is the difference between a ketch and a yawl? The most important difference between a ketch and a yawl are the position and height of the mizzenmast. The mizzenmast on a yawl is located aft of the rudder, is shorter than the mainmast and doesn't carry a mainsail. On a ketch, it's nearly as long as the mainmast and carries a mainsail.

There are a wonderful lots of DIY changeability shows on the cable airwaves these days.

Rick the rigger

There are SO many errors on this site it really should be taken down.

First major mistake is to say you are no longer afraid of the sea.

One that truly gets up my nose is the term ‘fully’ rigged ship. It’s a FULL rigged ship!! Your mast names are the wrong way round and just because there may be 3 it doesn’t automatically mean the one in the middle is the main.

I could go on and totally destroy your over inflated but fragile ego but I won’t. All I will say is go learn a lot more before posting.

Shawn Buckles

Thanks for your feedback. If you like to point out anything more specific, please let me know and I will update the articles. I’ve changed fully-rigged to full-rigged ship - which is a typo on my part. I try to be as concise as I can, but, obviously, we all make mistakes every now and then. The great thing about the internet is that we can learn from each other and update our knowledge together.

If you want to write yourself and share your knowledge, please consider applying as a writer for my blog by clicking on the top banner.

Thanks, Shawn

Well, I feel that I’ve learned a bit from this. The information is clear and well laid out. Is it accurate? I can’t see anything at odds with the little I knew before, except that I understood a xebec has a square rigged centre mainmast, such as the Pelican ( https://www.adventureundersail.com/ )

Hi, Shawn, You forgot (failed) to mention another type of rig? The oldest type of rig known and still functions today JUNK RIG!

Why are so many of the comments here negative. I think it is wonderful to share knowledge and learn together. I knew a little about the subject (I’m an Aubrey-Maturin fan!) but still found this clarified some things for me. I can’t comment therefore on the accuracy of the article, but it seems clear to me that the spirit of the author is positive. We owe you some more bonhomme I suggest Shawn.

As they say in the Navy: “BZ” - for a good article.

Been reading S.M. Stirling and wanted to understand the ship types he references. Thank you, very helpful.

This site is an awesome starting point for anyone who would like to get an overview of the subject. I am gratefull to Shawn for sharing - Thanks & Kudos to you! If the negative reviewers want to get a deeper technical knowledge that is accurate to the n-th then go study the appropriate material. Contribute rather than destroy another’s good work. Well done Shawn. Great job!

Good stuff Shawn - very helpful. As a novice, it’s too confusing to figure out in bits and pieces. Thanks for laying it out.

First of all I have to say that Rick ‘the rigger’ is obviously the one with the “over inflated but fragile ego” and I laughed when you suggested he share his knowledge on your blog, well played!

As for the content it’s great, hope to read more soon!

Alec Lowenthal

Shawn, I have a painting of a Spanish vessel, two masted, with. Lateen sails on both masts and a jib. The mainsail is ahead of the main mast (fore) and the other is aft of the mizzen mast. Would this be what you call lugger rig? I have not seen a similar picture. Thanks, Alec.

Thank you for your article I found easy to read and understand, and more importantly remember, which emphasises the well written.. Pity about the negative comments, but love your proactive responses!

This vessel, “SEBASTIAN” out of Garrucha, Almería, España, was painted by Gustave Gillman in 1899.

Sorry, picture not accepted!

Thank you for a very informative article. I sail a bit and am always looking for more knowledge. I like the way you put forth your info and I feel if you can’t say anything positive, then that person should have their own blog or keep their opinions to their-self. I will be looking for more from you. I salute your way of dealing with negative comments.

Thank you for a great intro to sailing boats! I searched different sailboats because I use old sails tp make bags and wanted to learn the difference. Way more than I ever expected. Thanks for all the work put in to teach the rest of us.

Your description of a cutter is lacking, and your illustrations of “cutters” are actually cutter-rigged sloops. On a true cutter, the mast is moved further aft (with more than 40% of the ship forward of the mast). A sloop uses tension in the backstay to tension the luff of the foresail. The cutter can’t do this.

Also, a bermuda-rigged ketch will have a line running from the top of the mainmast to the top of the mizzenmast.

wow great guide to rig types! thanks

Interesting guide, however I am confused about the description of the brig. You say the main mast on a brig can have a lateen sail, but in your picture it looks like a gaff sail to me. How is it a lateen sail?

Hi Shawn, thank you for taking the time to share this information. It is clear and very helpful. I am new to sailing and thinking of buying my own blue water yacht. The information you have supplied is very useful. I still am seeking more information on performance and safety. Please keep up the good work. Best Regards

mickey fanelli

I’m starting to repair a model sailboat used in the lake I have three masts that have long been broken off and the sails need replacement. So my question is there a special relationship between the three masts I do have reminents of where the masts should go. they all broke off the boat along with the sails I can figure out where they go because of the old glue marks but it makes no sense. or does it really matter on a model thank you mickey

Cool, total novice here. I have learnt a lot. Thanks for sharing - the diagrams along with the text make it really easy to understand, especially for a beginner who hasn’t even stepped on a sailing boat.

Daryl Beatt

Thank you. Cleared up quite a few things for me. For example, I was familiar with the names “Xebecs” and “Polaccas” from recent reading about the Barbary War. I had gathered that the two Barbary types were better suited to sailing in the Med, but perhaps they were less able to be adaptable to military uses,(but one might assume that would be ok if one plans to board and fight, as opposed to fight a running gun duel). Specifically, the strangely one sided August 1, 1801 battle between the USS Enterprise under Lt. John Sterett and the Polacca cruiser Tripoli under Admiral Rais Mahomet Rous. On paper both ships seemed nearly equal in size, guns and crew, but pictures of the battle are confusing. While the Enterprise is usually rendered as the familiar schooner, the polacca Tripoli has been pictured in radically different ways. Thus the Wikipedia picture by Hoff in 1878 used to illustrate the Battle shows a Brig design for Tripoli, indicating 77 years later, polaccas were no longer common.

Lee Christiansen

I am curious as to what you would call a modern race boat with a fractional jib,not equipped for full masthead hoist? Thanks Lee

Thanks Guy: The information and pictures really eliminate a lot of the mystery of the terminology and the meanings. Also appreciate the insight of the handling idiosyncrasies “hand” (staff) requirements to manage a vessel for one that has not been on the water much. I long to spend significant time afloat, but have concern about the ability to handle a vessel due to advancing age. The Significant Other prefers to sit (in AC comfort)and be entertained by parties of cruise line employees. Thanks again for the information.

Gordon Smith

Your discussion made no mention of the galleon, a vessel with either square-rigged Fore and Main masts and a shorter lateen-rigged Mizzen, or, on larger galleons, square-rigged Fore and Main masts, with a lateen-rigged Mizzen and a lateen-rigged Bonaventure mast, both shorter than either the Fore or Main masts. Also, it was not uncommon for a galleon to hoist a square-rigged bowsprit topsail in addition to the usual square-rigged spritsail.

Emma Delaney

As a hobbyist, I was hesitant to invest in expensive CAD software, but CADHOBBY IntelliCAD has proven to be a cost-effective alternative that delivers the same quality and performance.

https://www.cadhobby.com/

Leave a comment

You may also like.

What's that sail for? Generally, I don't know. So I've come up with a system. I'll explain you everything there is to know about sails and rigs in this article.

17 Sailboat Types Explained: How To Recognize Them

Different Types of Sailing and Racing Explained

How Are Sail Numbers Assigned? (And how to pick yours)

Own your first boat within a year on any budget.

A sailboat doesn't have to be expensive if you know what you're doing. If you want to learn how to make your sailing dream reality within a year, leave your email and I'll send you free updates . I don't like spam - I will only send helpful content.

Ready to Own Your First Boat?

Just tell us the best email address to send your tips to:

- CLASSIFIEDS

- NEWSLETTERS

- SUBMIT NEWS

Brief history of the Enterprise Class as it celebrates its 60th anniversary

Related Articles

Upcoming Events

Sailboat Rigging Specifications: Everything You Need to Know

by Emma Sullivan | Aug 1, 2023 | Sailboat Maintenance

Short answer: Sailboat rigging specifications

Sailboat rigging specifications refer to the measurements and details of the various components that make up a sailboat’s rig. This includes the type and size of the standing rigging (such as shrouds and stays), running rigging (such as halyards and sheets), mast height, boom length, and sail dimensions. These specifications are essential for proper performance, safety, and handling of a sailboat.

1) Understanding Sailboat Rigging Specifications: A Comprehensive Guide

Understanding Sailboat Rigging Specifications: A Comprehensive Guide

Sailing enthusiasts often find themselves entranced by the beauty and grace of a sailboat slicing through the water, powered solely by the wind . But behind every successful sailboat is a well-designed rigging system that plays a crucial role in its performance and safety. In this comprehensive guide, we will delve into the world of sailboat rigging specifications, unraveling the intricacies and shedding light on the key aspects every sailor should understand.

To embark on this journey of unraveling sailboat rigging specifications, one must first comprehend their fundamental purpose. Rigging refers to the various components that support and control the sails, enhancing their efficiency in harnessing wind power. It comprises intricate networks of wires, ropes, blocks, pulleys, and fittings meticulously designed to distribute loads evenly across the hull while enabling precise control over sail adjustments.

The importance of understanding these specifications cannot be overstated. Rigging functions as an interconnected system where even slight adjustments can have a profound impact on sailing performance . Familiarity with rigging specifications empowers sailors to optimize their boat’s performance while ensuring safe navigation under diverse weather conditions.

Let’s dive deeper into some essential elements that make up a sailboat ‘s rigging specification:

1) Standing Rigging: The standing rigging forms the backbone of any sailboat ‘s rigging system. It consists predominantly of stainless steel wire cables known as ‘stays’ or ‘shrouds,’ which hold up the mast and distribute its loads across multiple points on the hull. Understanding how factors like wire diameter (gauge), construction (1×19 or 7×7), material grade (316 or 304 stainless steel), and tension affect overall stability plays a vital role in maintaining a balanced vessel capable of handling varying wind conditions.

2) Running Rigging: Unlike standing rigging that remains static during normal sailing operations, running rigging controls various sail adjustments in response to wind conditions. It includes halyards, sheets, and control lines that enable raising and lowering sails, trimming them for maximum efficiency, and altering boom positions. Knowing the properties of different ropes (known as lines) like rope material (nylon, polyester, or Dyneema), diameter, and construction allows sailors to optimize their boat’s performance while ensuring ease of handling.

3) Sail Controls: Sail controls encompass a variety of mechanisms essential for regulating the shape and tension of the sails. Devices such as sail tracks, winches, blocks, travelers, and cleats collaborate harmoniously with rigging components to achieve precise control over sail shape, twist, camber, draft position – all crucial factors influencing both speed and safety. Familiarity with these specifications enables sailors to adeptly adjust their sails’ performance based on wind strength and direction.

4) Safety Considerations: Rigging specifications hold a critical role in ensuring safety during sailing ventures. Inspecting the rigging thoroughly before setting sail is imperative. Checking for corrosion or wear on wire cables, fraying on ropes or lines can help prevent disastrous failures mid-journey. Additionally, understanding load limits associated with each component guarantees sailors neither underload nor overload any part of their rigging system.

By now it should be evident that understanding sailboat rigging specifications is indispensable for every sailor aiming to unlock their vessel’s true potential while prioritizing safety. With constant advancements in materials technology providing an array of options for upgrading rigging systems tailored to specific sailing needs – from club racing to bluewater cruising – keeping abreast of new developments becomes even more crucial.

Maintaining a well-maintained rigging system is not merely about technicalities; it represents an art form that requires skillful orchestration by blending engineering prowess with a deep appreciation for the timeless elegance embodied by these majestic vessels. So next time you set out on your sailboat, take a moment to marvel at the intricate rigging system that steers you toward adventure and understanding .

2) How to Determine the Right Sailboat Rigging Specifications for Your Vessel

In the exciting world of sailing, the rigging of your sailboat plays a crucial role in ensuring a successful, safe, and enjoyable voyage. Just like a well-tailored suit, finding the right specifications for your vessel’s rigging is essential to maximize performance on the water. Whether you’re an experienced sailor or a novice embarking on your first adventure, understanding how to determine the ideal sailboat rigging specifications can make all the difference.

But fear not! We’ve got you covered with some expert tips to help you navigate through this process. Let’s dive in and unravel the mysteries behind finding the perfect rigging setup for your vessel.

1) Understand Your Boat

Before delving into determining proper sailboat rigging specifications, it’s important to comprehend your boat inside out. Consider its design, size, weight distribution, and intended use. No two boats are exactly alike, and thus each requires specific considerations when it comes to rigging .

For example, if you own a racing yacht designed for speed and agility, your rigging will likely be tuned for optimal aerodynamics while maintaining stability. On the other hand, if you have a leisurely cruising boat built for comfort and relaxation, your rigging may focus more on ease of handling without compromising safety.

2) Seek Professional Advice

While it’s tempting to rely solely on your own instincts and knowledge when determining sailboat rigging specifications, consulting a professional is highly recommended. An experienced rigger or naval architect can provide valuable insights based on their expertise and extensive background in handling various vessels.

These professionals can assess factors such as mast height/length ratio (aspect ratio), headstay tension requirements, shroud angles/tensions (depending on single or multiple spreaders), boom height relative to deck level – just to name a few critical parameters that contribute to successful sailboat performance.

3) Analyze Sail Plan

Your boat’s unique characteristics should be accounted for when analyzing the sail plan. Consider the number and types of sails you have or plan to use—main, jib, genoa, or spinnaker—and their respective sizes and geometries. The size and positioning of your sail ‘s luff length, foot length, and clew height will influence rigging decisions.

By understanding the relationship between your vessel’s sail plan and rigging, you can optimize control and response while sailing in various wind conditions. For instance, a high-performance racing yacht may require a more powerful rig with adjustable backstays or hydraulic tensioners to handle large headsails effectively.

4) Safety First

While we all love chasing speed on the water, it’s crucial not to neglect safety considerations when determining rigging specifications. Overloading the rigging beyond its limits can lead to disastrous consequences. Carefully analyze the breaking load ratings of wires/ropes and fittings used in your sailboat’s rig system.

Additionally, regular inspections and maintenance are paramount to detect any potential weaknesses before they become serious issues during your sailing adventures . Never compromise safety for performance gains; instead, strike a balance between both aspects for an enjoyable and secure experience on board.

5) Experiment & Fine-Tune

When it comes to sailboat rigging specifications, finding the perfect setup might require some trial-and-error experimentation combined with meticulous fine-tuning. Keep track of changes made and their effect on different sailing conditions.

Don’t be afraid to reach out to other sailors within your community who might have similar vessels or experiences as they can offer valuable suggestions based on their firsthand encounters. Joining online forums or attending boat shows/seminars can also provide opportunities for networking with like-minded enthusiasts eager to share insights into optimizing sailboat rigging setups.

In conclusion, determining the right sailboat rigging specifications is an art that combines science, experience, and personal preferences. By thoroughly understanding your boat ‘s characteristics, seeking professional advice, analyzing your sail plan, prioritizing safety, and embracing experimentation, you can find the perfect balance that suits your vessel’s needs. So, hoist the sails high and set off on unforgettable sailing adventures with confidence and finesse!

3) Step-by-Step Process: Setting Sailboat Rigging Specifications like a Pro

Title: Mastering the Art of Setting Sailboat Rigging Specifications: A Professional’s Step-by-Step Process

Introduction: Setting sail on a mesmerizing adventure calls for meticulous attention to detail when it comes to sailboat rigging. Even the slightest miscalculation or oversight can have a significant impact on safety, performance, and overall sailing experience. In this article, we unveil a comprehensive step-by-step process that will empower you to set sailboat rigging specifications like a true professional – ensuring smooth navigation and maximizing your boat’s potential. So, fasten your seatbelts (or should we say lifelines), as we embark on this exciting journey!

1) Understanding the Basics: Before diving into the specifics, let’s brush up our understanding of sailboat rigging. Sailboat rigging refers to the collection of intricate systems that support and control the sails aboard a boat . It includes elements such as mast, shrouds, stays, halyards, sheets, and various fittings responsible for tensioning and maneuvering sails .

2) Inspection is Key: To begin our step-by-step process, inspect your entire sailboat meticulously. Look out for signs of wear and tear in the hardware components including shackles, turnbuckles, blocks, cleats – anything that plays a crucial role in securing your rigging. Ensure all fixings are tight and secure; any loose connections can be disastrous while hoisting sails in rough waters .

3) Evaluate the Lines: Next up is evaluating your lines – halyards and sheets. Check for degradation caused by exposure to UV radiation or harsh weather conditions . Replace worn-out lines promptly as frail ropes pose great risks during maneuvers when under high loads.

4) Determine Your Sailing Style: Now it’s time to assess your unique sailing style! Are you an adrenaline-seeking racer or more inclined towards leisurely cruising? This assessment helps understand the necessary adjustments required in rigging setup. Racers typically prefer minimal weight and maximum control, while cruisers prioritize ease of handling and comfort. Knowing your preference will allow you to fine-tune your rigging specifications accordingly.

5) Measurements That Matter: Precise measurements play a vital role in achieving the desired rigging tension and performance. Carefully measure the heights of your mast, boom, and other essential spars to ensure proper alignment during installation . Always refer to manufacturer guidelines for recommended measurements as they vary across different sailboats.

6) Understanding Tension: To create optimal sail shape and performance, understanding tension is crucial. Referred to as tuning the rig, setting proper tension in shrouds and stays allows for controlled sail draft and minimizes distortion under varying wind conditions. Consult professional tuning guides or seek assistance from sailing experts if needed; mastering this skill could significantly impact your boat’s overall stability and speed.

7) Partnering with Professionals: Suppose you find yourself overwhelmed by the complex world of sailboat rigging specifications. In that case, partnering with professionals can be an excellent way to gain valuable insights and guidance specific to your boat’s make and model. Rigging specialists possess extensive knowledge regarding different components, methodologies, and cutting-edge advancements in the industry – guiding you towards optimal rigging configurations tailored to suit your needs.

8) Going Beyond Theory: Putting theoretical knowledge into practice through experimentation is essential when it comes to refining sailboat rigging specifications like a pro. Head out on shorter cruises initially where you can gradually fine-tune adjustments based on real-world sailing experiences . This hands-on approach ensures you become intimately familiar with your boat ‘s behavior under various wind conditions – turning you into a confident skipper who knows their vessel inside out.

Conclusion: Rigging a sailboat may seem daunting but breaking it down into manageable steps demystifies this intricate process. By understanding the basics, inspecting meticulously, evaluating lines, accounting for sailing style, measuring accurately, tensioning skillfully, seeking professional guidance when needed, and continuously experimenting, you’ll be well on your way to becoming a pro at setting sailboat rigging specifications. So go ahead – seize the wind and waves with confidence as you embark on unforgettable journeys aboard your perfectly rigged vessel !

4) FAQs about Sailboat Rigging Specifications Answered

When it comes to sailboat rigging, there are lots of questions that may arise. Understanding the specifications and requirements can be a bit confusing for beginners and even experienced sailors. Fear not! We have compiled some frequently asked questions about sailboat rigging specifications to provide you with comprehensive answers.

1. What are sailboat rigging specifications? Sailboat rigging specifications refer to the guidelines and requirements set for the rigging components on a boat. It includes details such as the type and size of wire used, fittings, tensions, and other important measurements needed to ensure the stability and safety of your sailboat’s mast and sails.

2. Which factors determine the sailboat’s rigging specifications? Several factors come into play when determining sailboat rigging specifications: boat size, displacement, type of sailing (cruising or racing), mast height, length overall, beam width, keel design, mast construction material (aluminum or carbon fiber), among other considerations. Different boats will have different specific requirements based on these factors.

3. Why is it important to adhere to proper sailboat rigging specifications? Adhering to proper sailboat rigging specifications is crucial for maintaining safety while at sea. Rigging components are responsible for supporting the mast and sails in changing weather conditions and intense pressures caused by wind. Without adhering to appropriate specifications, the integrity of your rig could compromise stability or even lead to catastrophic failures like broken masts or torn sails .

4. How often should I inspect my sailboat’s rigging ? Regular inspections of your sailboat’s rigging are essential for identifying any signs of wear or damage which could lead to failure. The frequency of inspections depends on various factors such as how often you use your boat, sailing conditions (rough or calm waters), saltwater exposure (corrosion risks), and age of components. Most experts recommend at least an annual rig inspection, but it’s always a good idea to consult your boat manufacturer or a professional rigger for specific guidance.

5. Can I upgrade my sailboat’s rigging specifications? Yes, upgrading a sailboat’s rigging is possible and sometimes even necessary. Upgrading can improve performance, reduce weight aloft, increase durability, and enhance safety. However, determining the appropriate upgrades requires careful evaluation of your boat ‘s characteristics and intended use. Consulting with experienced sailors or professional riggers will help you make informed decisions about potential upgrades.

6. What are some common signs of worn-out or damaged rigging components? There are several signs that indicate worn-out or damaged rigging components: loose wires or strands, broken strands, rust or corrosion on fittings and wire surfaces, elongation/stretching of wire cables beyond their original length, fraying or chafing of cables near attachment points. Recognizing these symptoms early allows for prompt replacement before they compromise the structural integrity of your sailboat.

In conclusion, understanding sailboat rigging specifications is crucial for the safety and longevity of your vessel. Adhering to proper specifications not only ensures stability but also minimizes the risk of failures while sailing. Regular inspections and timely replacements are key to maintaining reliable rigging. Remember to seek advice from professionals when making changes or upgrades to ensure you choose the right specifications for your boat . Keep sailing safe and enjoy the adventure!

5) The Importance of Sailboat Rigging Specifications: Ensuring Safety and Performance

When it comes to sailboats, safety and performance are paramount. One crucial aspect that often gets overlooked is the rigging specifications. Rigging refers to the system of ropes, wires, and hardware that support and control the sails, ensuring smooth navigation on the water . While it may seem like a mundane technicality, proper sailboat rigging specifications play a pivotal role in both the safety of the crew and the boat’s overall performance.

First and foremost, sailboat rigging specifications are essential for ensuring the safety of everyone onboard. A well-maintained and correctly installed rigging system reduces the risk of accidents, such as mast failure or rig collapse. Sailboats can encounter powerful winds and turbulent waters that put immense strain on their rigging. With precise specifications, sailors can have peace of mind knowing that their boat’s rigging is up to par and capable of withstanding challenging conditions.

Additionally, sailboat rigging specifications are crucial for optimizing performance on the water. An improperly rigged boat can experience inefficiencies in sail trim, resulting in decreased speed and maneuverability. Precision is key when it comes to adjusting tensions in various parts of a sailing vessel’s rigging system – from shrouds and stays to halyards and sheets – as these adjustments directly impact how efficiently a boat harnesses wind power for propulsion.

Not only do accurate sailboat rigging specifications enhance a boat’s speed potential but they also contribute to improved handling characteristics. When every element of the rigging is properly tensioned according to manufacturer recommendations or customized preferences, sailors have better control over their vessel’s stability both while cruising or racing competitively.

Furthermore, maintaining appropriate sailboat rigging specifications aids in prolonging the lifespan of an entire sailing craft. Regular inspections will help identify any signs of wear or damage on hardware components such as clevis pins, turnbuckles, or swage fittings; thus allowing timely replacements before they lead to catastrophic failures. Moreover, old or worn-out rigging can gradually cause stress points to develop on the mast, deck, and hull – compromising structural integrity over time. With meticulous attention to detail and adherence to specifications, sailboat owners can prevent costly repairs or potentially life-threatening situations .

Aside from safety and performance benefits, adhering to sailboat rigging specifications also demonstrates a high level of professionalism. Whether you are an experienced sailor or a novice boat owner, consulting and complying with manufacturer guidelines or hiring expert riggers showcases a deep understanding and respect for the intricate mechanics of sailing vessels. It exemplifies a commitment towards mastering the art of sailing and upholding industry standards.

In conclusion, sailboat rigging specifications might appear insignificant at first glance; however, their importance cannot be underestimated when it comes to safety, performance optimization, vessel longevity, and professional responsibility. By ensuring that every aspect of a sailboat’s rigging complies with established guidelines or customized preferences within safe parameters provided by manufacturers and experts alike — sailors can enjoy not only smooth-sailing experiences but also preserve the overall value of their prized watercraft. So before setting off on your next nautical adventure, take the time to pay attention to your sailboat’s rigging specifications – it could make all the difference in creating a memorable voyage while safeguarding everyone onboard.

6) Top Factors to Consider when Choosing Sailboat Rigging Specifications

When it comes to sailboat rigging specifications, there are several factors that every sailor should consider before making a decision. The rigging plays a crucial role in the performance and safety of your sailboat, so choosing the right specifications is paramount. In this article, we will outline the top factors to consider when selecting sailboat riggin…

1) Type of Sailboat : The first factor to consider is the type of sailboat you own or plan to purchase. Different types of sailboats have different rigging requirements. For example, a racing yacht would require a more sophisticated and adjustable rigging system compared to a small pleasure cruiser. Understanding your sailboat’s design and intended use will help you narrow down your options.

2) Material: The material used for the rigging greatly impacts its durability and performance. Stainless steel is widely regarded as the best choice due to its resistance to corrosion and high tensile strength. However, there are different grades of stainless steel, such as 316 marine-grade or 304 structural-grade, each offering varying levels of durability and cost-effectiveness.