~ Back to Rigging ~

Wire Rigging Vs. Synthetic Rigging Vs. Rod Rigging

Synthetic rigging has been getting more and more common recently. rod rigging has lost some popularity in the past decade due to parts availability issues from manufacturers. wire rigging has remained tried and true to the test of time. in looking at each of these stay materials we find some advantages and disadvantages. let’s take a look….

WIRE RIGGING:

Wire rigging, generally, is the most common form of standing rigging found on sailboats today. 1 x 19 standard stainless steel specifically is the most common style of wire used. All of these types of wires can be found in both metric and imperial size ranges except for Dyform/ Compact Strand which is only available in metric sizing (at least as far as I know). Stainless steel wire can come in many grades; in marine applications a minimum of 304 grade is recommended, but we [at TRC] won’t touch it unless it is the more corrosion resistant 316 grade.

Wire comes in as the lowest cost product of the three, especially when using swage fittings. Life expectancy is very good with regular inspection , 7-20 years or 15-25k nautical miles depending on use and region. It lasts not as long as rod, but longer than synthetics. It also is the stretchiest and most elastic of the three choices and therefore offers the lowest performance.

ROD RIGGING:

Nitronic 50 (XM-19) Rod rigging has extremely long life expectancy attributed to design (mono strand) and the composition of the alloy making it very corrosion resistant. It is arguable that the lifespan of a Nitronic 50 piece of rod will outlast all other stay materials. One of the recent misconceptions about rod is that it is very expensive to replace and also hard to find parts. Hence more and more people have been asking about converting their rod rigged boats to wire (but more on that below).

Contrary to recent rumors, rod rigging parts and service are readily available at The Rigging Company!

Rod rigging does require a more in-depth service protocol during recommended intervals, which includes unstepping the mast to inspect and re-head the rod as needed. It should be known that the cost for this is very reasonable, nowhere close to the cost of re-rigging. Yes, when dealing with complete rod replacement (not service) which is rarely the case, one can expect to pay a bit more for rod rigging, relatively speaking of course.

SYNTHETIC RIGGING:

The downsides of synthetic stays are they are generally more expensive (except single braid Dyneema perhaps) than the other stay materials out there. Even with great strides, claiming 10 years of lifespan with service, in the carbon fiber side of things, synthetic rigging will not last as long as the metal stuff. The last downside I always point out is, although some of these materials are extremely chafe resistant (varying depending on construction technique and material choice, of course), I will stand firm that they are no match to that of metal wire or rod.

INTERCHANGEABILITY OF STAY MATERIALS:

Lastly, I’d like to touch on the subject of switching from one stay material to another. As I mentioned above, many people with rod rigging have been asking about changing over to wire. I think this is mainly attributed to the lack of service centers and parts availability for rod rigging IMHO. I will try and keep this short and sweet by starting off with the fact that it will likely cost more money to change over the rod rigging to wire, even though wire rigging is slightly less expensive (again, generally speaking). There are attachment point changes as well breaking strength considerations which can become a problem especially when considering pin sizing.

~It will likely cost more money to change over the rod rigging to wire~

Conversely, upgrading from wire to rod rigging presents similar issues. Having said all of that, there are some (very few) boats with rod rigging that can easily get away with changing things over. Valiant is one that comes to mind. This is because they utilize conventional attachment points.

To finish this up, if talking about synthetic upgrades from rod or wire there are some better options for you. The main reason for this being a more viable option is that synthetic rigging was developed to be an upgrade from wire or rod (barring some of the newer super yacht designs, probably a non-point to you, the reader, since you are on this site). Whereas rod and wire rigging was primarily developed to be OEM equipment, not an upgrade option. Thus, if you have wire or rod…chances are, you are better off sticking with what was there originally, OR upgrading to synthetic.

Thanks for the read and please be so kind and leave us your thoughts below.

Similar Posts

Ac and the vor.

Some big news in the two sailing events that will always have my full attention. The Americas Cup has announced the return of the classic (yet modernly equipped) J Class boats for the 35th edition of the Americas cup taking place in 2017, in Bermuda. This will add some class back into the highly modern,…

Rod Rigging

In the world of sailboat standing rigging there are three common materials used, stainless steel wire, Nitronic 50 rod, and various types of synthetic fibers, which are becoming more and more popular. I want to talk today about Nitronic 50 stainless steel rod. This specific type of stainless steel is very strong and noble. Rod…

The New Volvo Ocean Race 2014-2015……

…….will have an all woman team. Awesome! Quite the line up as well. Boys you better step up your game. Remember, the new VOR boats will be one design. I can’t wait! [youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PdroQqOuMVE&w=560&h=315]

Synthetic VS. Vinyl Coated VS. Un-coated Stainless Steel Lifelines

Many people these days are looking towards synthetics or to un-coated stainless steel to replace their lifelines over the traditional vinyl coated lifelines of the past. First, let’s talk a little bit about the cons of using vinyl coated wire: the wire cannot be visually inspected for failure, the wire is typically made from a…

The Making of the J-Class “Atlantis”

Check out the level of quality and professionalism in this compressed yacht building video of the aluminum J Class, “Atlantis”. What an intense project. The yacht had been commissioned for a Dutch owner and the design was based on the original plans for a ‘Super J’, designed by Frank C Paine in the 1930’s. [youtube…

Still Here, Are You Coming Down?

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

32 Comments

I was looking at a Valiant 39 with rod rigging and my first reaction was to wonder if it was possible to change to standard wire rigging.

Thanks for the comment. The short answer yes, I think it would be a very simple swap on the Valiant Yachts due to their use of conventional, non-rod-specific, tangs (mast attachment points.

Good luck in your endeavors and let us know if we can help you further.

Great breakdown of wire, synthetic, and rod rigging! Your insights on the pros and cons of each type are invaluable. As a sailing enthusiast, I appreciate the detailed comparison that helps me make an informed decision for my boat rigging. The visuals and explanations make it accessible even for those new to the sailing world.

Hello, Thanks for this article, it was a lot educational. I have a Question I didn’t find anywhere. My J24 has 1×19 Dyform 3/16 shrouds and I started thinking that the tensions I m using from the North Sails tuning guide are referred to standard 1×19 shrouds, but Dyform are less stretcher and stiffer (so to speak). so the question is, should I have to use a different tension with Dyform, or it doesn’t matter? maybe less tension because it stretch less? Oh! one more thing, does tension gauge reading is correct in this shrouds? (as cable is more compact in diameter and stiffer)

The theory of what you are saying make sense. I would start with: A. A good static dock tune, B. Set the rig to your sailmakers tuning guide, C. Go sail. While sailing close hauled, observe the leeward shrouds (in the lulls). If you see the shrouds are just beginning to slack, then it’s PERFECT, and just follow the guide! If they look like they aren’t moving, take some turns off until they just begin to go limp (in the lulls). Once back at the dock, note the gauge settings and this should allow you to scale your pre-sail tension settings up and down, relative to your guide, from there.

At the end of the day it is important to remember the guide is just that, a guide. Eventually you will just feel things like the rig needs to be tighter or looser because it just… feels right. If you are running some heavier crew that day, you may soften things up, and visa-versa, etc…

Hope that helps and happy sailing.

I also thank you for this excellent summary! I’m cautiously returning to sailing in New England after a decades-long hiatus. I bought a 1982 Catalina 27, and I’m unsure of the age of the rigging or if it needs to be replaced. How do I determine such a thing? Also, if you have an inspection/maintenance checklist/schedule, I’d be very glad to see it. Thanks.

Thanks for the kind words. Other than asking the previous owner you can send along some pictures of things to [email protected] and we can likely tell once we put our eyes on things.

I own a nine meter cruising catamaran. I had the mast and rigging done about 16 years ago. Being a cat the deck is one meter above the waterline so the rigging isn’t close to the water. The rigging is 8mm Compact 1 * 19 S/S. I do no more than 500 nautical miles per year (generally less). Should I look at replacing my rigging soon or can I probably get a few more years from it?

Where on the planet does the boat spend most of it’s time?

“Cobwebs” is moored in a sheltered area on the southern shores in Lake Macquarie, about 80 miles north of Sydney. Most of the weather systems are south westerlies and passes overhead as Cobs is moored close to the land. I check the rigging on a regular basis and clean the lower sections with soapy fresh water. It’s going to cost me about $1600 Aus to replace the rigging so if I can stretch this out for a couple of years I will be happy to do so. Your thoughts on this issue will be most appreciative, regards Ross C.

If this lake is fresh water you are very likely in better shape than those on Saltwater. The three factors are: salt air and water content, how close you are to the equator (sunlight), and also use. Use, encompasses the boat sitting at the dock. At the dock, the rigging experiences what they call “Cycle Loading” even if not sailed. So fresh water and the rigging being removed and stored when the boat is not in use will generally offer the longest lifespan.

Having said that 16 years even in those ideal conditions is nearing it’s end. So inspect it more than regularly, and prepare yourself for the inevitable.

PS – $1600 sounds reasonable for what it’s worth.

I hope that’s somewhat helpful.

Cheers, ~T.R.C.

SUPERBLY INFORMATIVE ARTICLE (MARGINALLY DATED OR OTHERWISE). OF THE SLOOPS I HAVE OWNED, ALL WERE RIGGED WITH WIRE (1-19) AND, DESPITE OPEN OCEAN AIR (20-35 KNOTS) BEING THE PLAT DU JOUR IN HAWAIIAN WATERS, I NEVER HAD AN ISSUE OF ANY SORT. THANKS TO YOUR FINE REVIEW i SHALL STAY WHERE I AM IN THE FORTHCOMING RE-RIGGING AND LEAVE THE ROD AND SYNTHETICS TO THE THOSE OF THE RACING CLASSES. MANY THANKS AGAIN… AND I SHALL REFER TO YOUR SITE OFTEN!

Thank you for your super helpful article, as it’s really informative having a side by side comparison for the three rigging types in one place. I have a 25′ trailerable coastal cruiser that I’m pondering switching from wire rigging to synthetic. The spreaders, though, just have a filed groove on the end for the shrouds to pass through (and the small holes on either side with which to wire the shroud in place). How do you eliminate chafing and make sure the shrouds stay in place with synthetic rigging running over the end of the spreaders? Cheers, Brandt

Find a piece of heavy rubber or vinyl or plastic tubing that the stay material fits through freely. Then cut about 2″ or so of said tubing with nice clean ends. Then file the slots open to accept said piece of rubber tubing or the like. Then, roll up a piece of sand paper to make the edges smooth and soften the aluminum slot. This should give you a fairlead and allow you to seize the synthetic stay to the spreader as you would with wire. The tubing should acting as a ferrule or buffer between metal slot and synthetic rope.

Hope that makes sense and is helpful.

Good Luck, ~T.R.C.

Good article but you never gave us an idea how much does rod last like you did with wire. Is there a guidance number of years and miles? Thanks

Great point! There’s always something missing.

We’ve written about this in a blog called “Rod Rigging” which is linked in the article, but it is’t clear.

Thanks! ~T.R.C.

This article should be updated. Synthetic rigging suppliers now say that it should be sized based on creep rather than breaking strength. Synthetic rigging tends to be much more elastic than wire rigging.

Thanks Jake,

No doubt, this (creep) is a major factor in choosing the right stay material size. Carbon rigging perhaps being the exception, but I am curious for more information on this.

We will indeed update this soon. For now our suppliers still size by tonnage. Also the pin sizes associated with the stay’s diameter are a factor in how we decide which diameter stay your boat requires.

Thanks for caring and thanks for the comment. Most of these seemingly simple write ups require regular updates as the market and the knowledge associated is changing constantly.

It’s comments like these that help us stay sharp.

Regards, ~T.R.C.

- Pingback: Why Choose Dyneema Rope vs Steel Wire Rope For Heavy-Duty Rigging?

I am going ocean sailing on a hallberg rassy 26 the rug needs replacing. Its all 6mm1x19 the back stay is 5mm I want to change to dyform the same size with stalok fittings to make it stronger. Your thoughts please

I am thinking of taking my hallberg rassy 26 on ocean passage and need ro renew the standing rigging she has 6mm all round and a 5 mm baxkstay I want stronger so am rhinking of using dyform same sizes with stalok fittings. Any thoughts ?

Thanks hope that helps and let us know if we can help you out further.

I have a C & C 42 Landfall with rod rigging. 1978 year is old but it is what i could afford. Think about long cruising at 68 but want somebody to look at rigging before i go. Atlantic Yacht Basin got all my money and say dead batteries? They laugh they fixed alternator and recommend i come back.

Thanks How does one measure tension in Aramid stays? SS

Very good question…I would use a Loos and Co. rigging tension gauge . It has nice, fair nylon rollers that will agree with the fiber stay materials.

In my mast with rod uppers there is a clindrical device that holds the rod ends at each side. Can the rods be removed? And how is the clindrical device held to the mast?

Hi Ernie, those seem exactly like the tangs we warn about in this blog….. https://theriggingco.com/2015/02/20/rod-rigging/

Also this has a technical drawing of the tangs that you are asking about (pretty sure).

YES, you can remove them, but you may find that they are more than you bragined for. HEAT is recommended.

Please call or email us for further assistance. We’d be glad to help.

Thanks for Reading,

Informative article. I am looking at a boat now with carbon mast and boom with PBO rigging. I took particular note of your comment on PBO “good luck with that one”. What do you mean by that? I am assuming that you are not a fan of PBO rigging.

Hi Charlie,

Another super informative post thank you! If you fancy a holiday in NZ then my wire rigging needs replacing next year. Also the spinnaker halyard keeps jumping out of the sheave at the top of the mast requiring someone to go up every time to get it down. As you can imagine this is getting quite tiresome! Anyway we will get the mast out next year to sort it. We do have a good rigging team here in Christchurch who can sort it. (unless you fancy a holiday that is…?!) ha ha. By the way is that the reflection on the transom of that yacht? What a great paint job!

HA! Thanks Viki! Actually, the wife and I have always quite fancied a vacay to NZ. It may be a long shot, but doable. We’ll need to exchange a few emails, answer a few questions. First let’s see what the wife says.

Yeah, that boat is incredible.

Username or Email Address

Remember Me

Lost your password?

Review Cart

No products in the cart.

- Privacy Overview

- Strictly Necessary Cookies

This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Strictly Necessary Cookie should be enabled at all times so that we can save your preferences for cookie settings.

If you disable this cookie, we will not be able to save your preferences. This means that every time you visit this website you will need to enable or disable cookies again.

- Boats & Gear

- Instructional

- Cruising Stories

- Cruising Destinations

- Race Results

- Race Reports

- Racing Technique

- Submit a Classified Ad

- Boats for Sale

- All Classifieds

- Terms & Conditions

- Your Dashboard

- Seattle Area Racing Calendar (SARC)

- 48° North Cruising Rally

- Croatia Flotilla

- Winds of Change: Rod Rigging Functionality, Interchangability, and Availability Considering Industry Changes

- Boating News

This article, by Lisa Vizzini, was originally published in the June 2017 issue of 48° North.

Earlier this year, the sailboat industry was shaken when Hall Spars and Navtec Rigging Solutions closed their United States operations. Over the years, Navtec and Hall shared many progressive, engineering driven, high profile projects. The loss of these two innovative domestic manufacturers leaves many, especially those with rod-rigged boats, asking who will fill the voids; and more specifically, about the future of rod rigging availability.

Hall Spars, founded in 1980, fabricated high quality aluminum, and later carbon, spars and rigging components. Their state-of-the-art plant in Rhode Island boasted a 185’ carbon autoclave. When I visited in 2009, Nan Hall proudly showed off the 65’ carbon boom and described the process for building the 179’ mast for the modern J-Class sloop, Lionheart . Over the years, many sailors had the pleasure of directly speaking with Nan Hall about their Hall-rigged project. Nan was always patient and courteous. While Hall Spars closed their US facility, Hall Spars New Zealand and Holland were still operating. At the time of this writing, new developments are still taking place. North Technology Group (the corporation that encompasses North Sails and other businesses) has purchased Hall Spars Worldwide. It is good to know that the intellectual property at Hall is not going to be lost.

In 1970, Navtec was founded by Ken King with the goal to bring better rod rigging technology to the marketplace. Their initial customers were America’s Cup contenders. At Navtec, Beau LeBlanc, Ty Goss, and other brilliant engineers were consistently forthcoming with information about rigging and hydraulics when asked by enthusiasts and professionals alike. Ty thoughtfully explained the intricacies of rod parts to me on more than one occasion.

Though Hall’s closure came as a surprise to many, signs that Navtec was on the edge – such as production delays and various delivery issues – have been apparent for at least a decade. The good news is that Navtec’s slow decline gave the industry time to adjust. In other words, these closures do not mean the demise of rod rigging in the United States, though they may cause a price increase for rod rigging.

Considering these industry changes, this is a good time to examine some of the similarities and differences in how rod and wire rigging function, what the processes for replacement entail, and some best practices for maintenance and inspection.

Many cruising boats were originally designed for wire rigs and there is rarely a reason for those boats to consider going to rod. Wire offers excellent value, longevity and availability the world over. A significant majority of sailboats still have wire rigging.

Rod rigging generally offers some better performance characteristics, and can be seen on a variety of boats, like many J/Boats, C&C, Beneteau, Waterline, Sabre, and Valiant Yachts, as well as custom racers and cruisers.

Rod is constructed from Nitronic 50 stainless steel, a material different from the 316 or 304 stainless steel usually used for wire standing rigging. Nitronic 50 better resists elongation, corrosion, and fatigue cycling. For a given diameter, rod has a higher tensile strength, and less windage and weight per foot of wire rigging. Because rod is not a woven or twisted construction like wire or other synthetics which are used for standing rigging, it is inherently more stable. The lack of stretch allows for less tension in the rig to support the mast, as well as a more reliable set of the rig under varying pressure and loads. This is especially important for rigs with swept back spreaders and masts that are highly adjustable as a part of sail trim and performance.

Considering a switch from rod to wire, or vice versa, should involve careful examination of the rig design, shroud angles, mast components, stiffness of the rig, load characteristics and bending moments.

A mast with tangs for marine eyes can be a simple switch from rod to wire. Elements affecting this option would be rod to wire size, chain plate pin size, and elongation concerns. Any replacement of rod with wire must have the same or greater minimum breaking load. The wire size selected must match the current mast tang and chain plate pin size or the tangs and chain plates would need to be changed to fit.

The stretch factor and the mechanical tensioning of the stay or shroud need to be analyzed carefully. It is possible that a long run of type 316 wire could elongate enough that the turnbuckle becomes two-blocked or runs out of adjustment before the wire is adequately tensioned.

A mast with rod stem ball receptacles is likely to be more challenging to convert to wire. This can involve removal of older stem ball tang sets, installation of proper fit compression tubes, bolts, and new tangs for marine eyes or other wire fittings. The sailor will have to weigh the cost of this with the cost of the rod replacement, and think about the different properties of the rigging types.

How long rigging lasts is subject to many different factors: age, miles, loads in comparison to break strength, sailing conditions and environmental conditions. Here in the northwest, rigging tends to last longer than warmer climes or those where air pollution is prevalent.

The heuristic for wire standing rigging is that it will provide good service for eight to ten years depending on the sailing conditions, environment, and use. It is a good idea to inspect at five year increments or 30,000 miles, which ever comes first.

By comparison, rod should be inspected after a maximum of 40,000 to 60,000 sailing miles or six years, whichever comes first. A proper inspection involves un-stepping the mast, scanning the rod inch by inch, and inspection of each cold head.

If issues are discovered with the rod heads and there is enough room in the turnbuckles, or longer screws can be used, a new cold head can be formed. It is recommended that the turnbuckles be replaced at least every ten years. Often there will be a stainless or aluminum tube called a “bend” over the rod where it passes through the spreader. The spreader bends are set at a precise angle and this can sometimes mean that the rod in this position will need to be replaced for proper fit of the shroud.

Taking care of your rod rig has similarities to caring for a wire standing rig. Like wire or other rigging materials rod wears out from cycling, fatigue, and corrosion. It stands to reason that keeping the stainless clean, allowing it to breathe, and proper tension will prolong its life.

Here in the Pacific Northwest, any rigging shop that has previously been able to accommodate rod rigging repair and replacement projects can continue to offer that service, despite the changes in the industry.

Hayn Marine has purchased and taken ownership of the intellectual property (engineering drawings) from Navtec. They will continue, as they have been for several years, to provide quality rod parts.

Despite industry changes, rod rigging is still a viable, and sometimes necessary, choice for many sailors. It can hold a value position for sailors seeking predicable rigging performance for whom the cost of composite parallel construction rigging can be impractical.

Lisa Vizzini and her husband, Dan Kulin, are the owners and operators of Port Townsend Rigging .

Lisa Vizzini

Lisa Vizinni has owned Port Townsend Rigging and Spars (PTR) for more than twenty years, and is passionate about sharing her experience and helping the sailing community. Learn more about PTR at http://www.porttownsendrigging.com/

Featured , Events Coverage

Fisheries Supply Spring Swap Meet Set for April 20

March 4, 2024

Boating News , Featured

Columnist Lisa Mighetto Wins BWI Writing Award for Her 48N Story, “Once More, With Feeling”

February 23, 2024

Cruising , Featured , Events Coverage

Only Six Spots Remain on 48° North Cruising Rally July 28 – August 2… Register today!

February 13, 2024

Christina Wolfe of Orcas Island Wins Rolex Yachtswoman of the Year!

February 2, 2024

Come Visit 48° North at the Seattle Boat Show!

Cruising Destinations , Featured , Events Coverage

CYC Seattle’s Fridays in February Series 2024

January 26, 2024

Please verify you are a human

Access to this page has been denied because we believe you are using automation tools to browse the website.

This may happen as a result of the following:

- Javascript is disabled or blocked by an extension (ad blockers for example)

- Your browser does not support cookies

Please make sure that Javascript and cookies are enabled on your browser and that you are not blocking them from loading.

Reference ID: 4bdadb88-dbe0-11ee-815f-2a9e26148216

Powered by PerimeterX , Inc.

- BOAT OF THE YEAR

- Newsletters

- Sailboat Reviews

- Boating Safety

- Sailing Totem

- Charter Resources

- Destinations

- Galley Recipes

- Living Aboard

- Sails and Rigging

- Maintenance

- Best Marine Electronics & Technology

Replacing Your Sailboat Rigging

- By Wendy Mitman Clarke

- Updated: March 23, 2020

Whether you’re buying a used sailboat that’s new to you or you’ve owned your boat for decades, the standing rigging is what keeps the mast in place, and thus requires particular attention. How do you know when it’s time to re-rig? There are some obvious answers to this one — for instance, if your wire rigging has broken strands or if it’s suffering from “candy-striping,” i.e., rust-colored streaks swirling down the wire. The latter may indicate two things: one, that it’s simply surface rust, which you should be able to polish off, or two, that as the wire was being manufactured, a strand might have picked up some contamination during the process and is compromised, which is cause for concern. A third visual indicator are cracks in swaged fittings, some of the most common end fittings for wire. Cracks are hard to see (use a magnifying glass), and sometimes marks that look like cracks can be left by the machine used to create the swage. Then there’s just age, and this factor as a reason to re-rig is more subject to a boat’s history than anything else.

“There’s a rule of thumb, but it varies rigger to rigger,” says Steve Madden, co-owner of M Yacht Services in Annapolis and the head of its M Rigging division. “My belief is that you should be replacing your sailboat’s standing rigging every 10 to 15 years.” But this time frame also is variable, depending on the boat’s purpose and use. For instance, for an offshore bluewater boat, Madden recommends 10 years, and for a serious coastal cruiser, more like 12.

“The biggest thing we like to have is the history of the boat: what kind of boat it is, how it’s been sailed and where has it been sailed,” says Jay Herman, owner of Annapolis Rigging. “That history will affect what kind of life you get out of your standing rigging.” Some insurance companies, he says, will require a re-rig if you’re purchasing a used boat that has standing rigging older than 15 years.

Either way, Jimmie Cockerill, co-owner of the Rigging Company in Annapolis, recommends that for a sailboat with wire rigging, the mast should be pulled and all fittings and wire visually inspected every five to six years. And although rod rigging may be able to last longer than wire, it too needs to be serviced every five to six years to get the most life out of it. Sticking to the 10-year rule, Madden says, means that for the most part, any corrosion or failure points will be eliminated with a re-rig.

How the rigging has been tuned is also part of a boat’s story. For instance, Madden says, he recently had a customer whose 46-foot cutter had a rigging failure at six years. The customer had had the boat re-rigged, and during a trip to the BVI, the new wire stretched. The owner didn’t adjust the rigging to compensate for the stretch for several seasons. “That was a case of not knowing that the worst thing you can do to standing rigging is have it loose on the leeward side,” he says. “Sailboat rigging very rarely fails from being overloaded. There’s such a safety margin in rigging. So you’re sailing offshore and you’re looking at the windward shroud that’s taut, and that’s not the one to worry about. It’s when the leeward side starts flopping around that you’re asking for trouble.”

Stainless steel has a finite number of cycles — essentially, movements, whether fore and aft or side to side. “The theory is that it can take 10 to 15 years of cycling, but this continual motion when it’s unloaded is what fatigues the wire,” Madden says. “There’s no real way of measuring that. Die testing won’t pick it up, and it’s rare that a wire will give you warning before breaking.”

So how often should standing rigging be replaced? For all of these reasons, most riggers agree that when your sailboat’s standing rigging approaches 15 years old, it’s a good time to consider replacing it.

Wire or Rod Sailboat Rigging?

Riggers say the question of whether to rig with wire or rod is usually fairly easily answered: Run what you brung. In other words, if your boat already has rod rigging, with all of the end fittings to terminate the rods both on deck and in or on the mast, then sticking with rod will ultimately be less expensive than making the switch to wire. Likewise, if you already have wire with fittings that accommodate your boat and mast, stick with wire. Aside from the relative cost differences between rod and wire (rod is more expensive), what also makes a switch pricey is having to significantly modify the mast to accept the different rigging.

Although rod rigging is more common on racing boats, many well-known cruising-boat builders, such as Valiant, Bristol, J/Boats and Hinckley, have rod-rigged models. The benefits of rod are less stretch, less weight, less windage, and arguably longer life than wire, because there’s less possibility for corrosion of the rod itself.

That said, some sailors prefer wire over rod for a number of reasons. First, it’s easier to fix in remote places and on your own. With a spare mechanical end fitting, wire and the proper tools, you can replace a stay pretty much anywhere. Similarly, it’s easier to find usable replacement parts far from busy ports. Wire rigging is generally less expensive and easier to handle. Finally, rod rigging requires a particular type of terminus — called a cold head — that can be fabricated only with a purpose-built machine, which only a rigging shop will have. You cannot use a mechanical fitting on rod rigging.

In the past, long-distance cruisers typically chose wire rigging with mechanical fittings for all of these reasons. They also would carry a piece of wire as long as the longest stay on the boat — coiled and stowed, which undeniably was sometimes easier said than done — as well as spare end fittings and the tools needed to replace a broken shroud or stay. Today, with the advent of super-strong synthetic line such as AmSteel and Dyneema, the need for that extra wire and gear is eliminated. For instance, the Rigging Company makes a spare-stay kit that can accommodate either wire or rod rigging repairs, Cockerill says. It has a synthetic stay with an eye splice, a toolless turnbuckle (the Handy Lock, made by C. Sherman Johnson), quick-release fast pins with an attached lanyard, several high-strength Dyneema loops, and even a heavy-duty zip tie to fish loops in and out of holes in a mast.

“The idea is you come on deck with this small canvas bag and make it happen,” Cockerill says. “Let’s say you ripped a tang out of the mast; you can use a Dyneema loop to create another attachment point. A smaller loop is a makeshift chainplate attachment — you can attach it to a neighboring chainplate and attach the stay to it. It’s good enough to get you to safety and someplace you can make a more permanent repair.” Riggers say very few sailors re-rig from wire to rod or the reverse, but if switching is on your mind, have a professional make a full assessment first.

There are so many variables in the system — types of end fittings, types of masts, types of attachment points — that each boat will have its own specific requirements that can affect cost. For that reason, it’s difficult to give an accurate estimate of the cost of making the switch, even for an average 40-footer.

End Fittings for Sailboat Rigging

All standing rigging, whether rod or wire, has to end in a fitting that attaches to the deck and mast. The three most commonly used types of attachments are swaged and mechanical fittings for wire, and cold heads for rod. Generally, end fittings fall into a few classes: studs, eyes, forks and hooks, each of which comes in a dizzying array of sizes and configurations. There are multiple combinations and variations: For instance, if your mast has double tangs, most likely the end fitting will be an eye — although it can be a marine eye or an aircraft eye, which differ primarily in shape. All rod rigging terminates in a cold head, which accommodates the end fitting or is encapsulated by the end fitting. This could be a marine eye, a marine fork, a T-head or a J-hook, among others.

A swaged fitting is a terminus that’s attached using a machine called a swager. It rolls the end fitting through two opposing dies and compresses the fitting on the wire so tightly that it can’t pull out. “The theory is that you’ve crushed it so tightly that all the wires inside have just merged into one solid piece of stainless,” Madden says. Swaging must be professionally done, and the result is extremely strong and generally has a long life. Top manufacturers of swaged fittings are Hayn Marine Rigging Products, Alexander Roberts and C. Sherman Johnson.

Mechanical fittings can be applied using a few common hand tools by the mechanically handy DIY sailor, which is one reason they’re popular. The two primary manufacturers of mechanical fittings presently are Sta-Lok and Petersen Stainless, which produces Hi-MOD. Both are located in the U.K., and the products are distributed in the U.S. through vendors like Hayn, West Marine, Defender, and local chandleries and riggers. Generally, they consist of either three or four parts (Sta-Lok has three; Hi-MOD has four), including a sleeve; a cone; in Hi-MOD’s case, a crown wheel; and the terminal (an eye, fork, stud, etc.). If you follow directions, they are fairly straightforward to install, although not especially easy. “The mechanical fasteners are great in that you can terminate and then look inside to be sure it’s formed correctly, so you do have a way of inspecting your work,” Madden says.

However, they generally cost more than a swaged fitting; Herman says while Hi-MOD’s newer mechanical fittings are “definitely more user-friendly to assemble, they’re twice the cost of a swaged fitting.” Some riggers will recommend swaged fittings for the mast end of the rigging and mechanical fittings at the deck level: Corrosion is less prevalent at the top of the mast, and you can more easily and regularly inspect mechanical fittings at deck level, where they’re frequently subjected to salt water

Should You Replace Your Sailboat’s Rigging Yourself?

So you’ve determined your sailboat’s standing rigging needs work. Do you hire a pro or go it alone? Good question. Yes, doing it yourself will theoretically save money. For an average 40-foot boat, Cockerill estimates about $100 per foot to re-rig with wire rigging ($4,000), as well as the round-trip cost to haul and launch the boat and unstep and step the rig (an additional $2,500 or so). By taking on the labor yourself, you’ll probably save as much as $2,000 on the re-rigging cost, he says. Madden says that cost isn’t linear, though; as you go up in size (a bigger boat needs heavier wire and larger fittings), you’ll spend more. He’d estimate more like $4,600 for a 40-foot boat, but all of these numbers depend on how much is involved: Are there furlers? What kind of end fittings? Are the chainplates sound? Depending on the answers to those questions and others, a professionally done re-rig for a 40-footer could be closer to $6,000 or more.

If you go DIY, you will be limited to mechanical end fittings unless you hire a rigger to swage your end fittings. The Rigging Company gears much of its sales to DIY sailors and is beginning an e-commerce site to cater specifically to handy individuals. But Cockerill says it quickly becomes evident whether an owner feels comfortable enough to do the work. “You should be mechanically inclined,” he says, “and the way to find that out is if I start talking all this technical jargon and you decide whether you’re suited to handle that at all.”

Additionally, a DIY sailor needs to do plenty of research, particularly when it comes to wire quality, which is something professional sailboat rigging companies watch like hawks. Although anyone can walk into a local chandlery and buy wire, that doesn’t mean the wire is of the highest quality. Marine-suitable stainless wire is called 316 grade, but even that doesn’t mean you’re necessarily getting high-quality wire. Much depends on where it is manufactured; Herman and other riggers say the best wire today is coming from South Korea through a manufacturer called KOS, making wire to military specifications. It’s imported and sold through distributors like Alps Wire Rope.

“We only sell guaranteed-content, guaranteed-process wire,” Herman says. “There are other wires out there that are cheaper, but they’re not guaranteed.”

As for sources of wire and fittings, there are many, including major chandleries and vendors, like West Marine and Defender, as well as some private riggers, like Annapolis Rigging and the Rigging Company, which will work with you to define what you need and help you source parts and materials.

One thing all the riggers I spoke with expressed emphatically was that stainless steel needs oxygen to create a fine film of oxidation that protects the metal. The fastest route to crevice corrosion is to cover the metal with plastic or leather turnbuckle covers or to coat the fittings in tape. Enough tape to cover a cotter pin suffices; otherwise, leave the metal open to the air. Likewise, if you are re-rigging your sailboatboat, use the opportunity to check your chainplates (easily the subject of another article entirely), since that’s one of the most common points of rigging failure.

Another factor in your DIY decision-making process is simple: peace of mind. “Most of my clients say to me without any prompting, ‘This is one area I feel should be done by a professional,’’’ Madden says. “You’re out there offshore and there’s a squall coming and you start worrying about the craziest of things, and you don’t want to have any unknowns.” That’s especially true of the system that keeps the mast and sails up.

Wendy Mitman Clarke is currently between passages. She’s the director of media relations at Washington College in Chestertown, Maryland, and she and her family continue to pine and plan for the day they can return to the cruising life.

- More: How To , mast , Refits , rig , rigging , sails and rigging , Upgrades

- More How To

It’s Time to Rethink Your Ditch Kit

8 ways to prevent seasickness, how to de-winterize your diesel engine, for sale: hallberg-rassy 46, the reality of fixing up an old boat, meet the wauquiez 55, new program for female sailors.

- Digital Edition

- Customer Service

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

- Email Newsletters

- Cruising World

- Florida Travel + Life

- Sailing World

- Salt Water Sportsman

- Sport Fishing

- Wakeboarding

Many products featured on this site were editorially chosen. Cruising World may receive financial compensation for products purchased through this site.

Copyright © 2024 Cruising World. A Bonnier LLC Company . All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part without permission is prohibited.

- New Sailboats

- Sailboats 21-30ft

- Sailboats 31-35ft

- Sailboats 36-40ft

- Sailboats Over 40ft

- Sailboats Under 21feet

- used_sailboats

- Apps and Computer Programs

- Communications

- Fishfinders

- Handheld Electronics

- Plotters MFDS Rradar

- Wind, Speed & Depth Instruments

- Anchoring Mooring

- Running Rigging

- Sails Canvas

- Standing Rigging

- Diesel Engines

- Off Grid Energy

- Cleaning Waxing

- DIY Projects

- Repair, Tools & Materials

- Spare Parts

- Tools & Gadgets

- Cabin Comfort

- Ventilation

- Footwear Apparel

- Foul Weather Gear

- Mailport & PS Advisor

- Inside Practical Sailor Blog

- Activate My Web Access

- Reset Password

- Pay My Bill

- Customer Service

- Free Newsletter

- Give a Gift

Cal 2-46: A Venerable Lapworth Design Brought Up to Date

Rhumb Lines: Show Highlights from Annapolis

Open Transom Pros and Cons

Mailport: Charley Morgan, Locker Safety, Fast Bottom Paint

Do-it-yourself Electrical System Survey and Inspection

Install a Standalone Sounder Without Drilling

The Tricked Out Tillerpilot

Resolving Common Steering Problems

Top-notch Wind Indicators

The Everlasting Multihull Trampoline

In Search of the Snag-free Clew

The Cruising Sailor’s Argument for High-tech Fibers

Breaking Point: What Can Go Wrong With Your Yanmar?

Rudder Mods for Low-speed Docking

Using Heat to Bend PVC Pipe

Mildew-resistant Caulks for Boats

Can We Trust Plastic Boat Parts?

Repairing Molded Plastics

Mailport: Marine plywood, fuel additives, through bolt options, winch handle holders

The Day Sailor’s First-Aid Kit

Choosing and Securing Seat Cushions

Cockpit Drains on Race Boats

Rhumb Lines: Livin’ the Wharf Rat Life

Resurrecting Slippery Boat Shoes

Shoe Goo’s Gift to Sailors

PS Advisor: Tank Monitor and Camera Mount Hacks

Tricks and Tips to Forming Do-it-yourself Rigging Terminals

Marine Toilet Maintenance Tips

Learning to Live with Plastic Boat Bits

The Ultimate Guide to Caring for Clear Plastic

Preventing Mildew in Marine Fabrics

- Sails, Rigging & Deck Gear

Standing Rigging: How Tight Is Right?

Standing rigging tension is a peculiarly under-addressed subject. Easy to see how it would worry a new boat owner or someone going to sea.

Most experts step aboard, yank or twang the shrouds and stays and mutter, Pretty slack, Too Tight, or, Thats about right.

Youll find in the sailing literature very few discussions of the question: What does tight mean?

Even riggers rarely explain how much tension they like to see.

There are a few sailors who like the rigging so tight you could send an elephant up the backstay. It can result in excessive loads and wear on fittings, chain plates and the hull. The ultimate penalty for those who can’t stand any sag in the forestay is what ocean racing sailors call a gravity storm or, less dramatically, dropping the rig.

Others like to take up the slack just enough so that the rig is at rest when the boat is motionless. This approach sometimes leaves excessive slack to leeward that can result in shock loads, excessive wear and misalignment in fittings. It may take longer, but the ultimate penalty is the same.

In between (and probably in the most logical position) are those who like to take up the slack and stretch the wire just a bit. This is frequently accomplished, at least for the stays, with an adjustable backstay. When sailing, especially on the wind, tighten down to minimize slack in the forestay. When reaching, running or at anchor, ease off.

But the question is: How much stretch…especially in the shrouds?

If you stretch the wire 5% of its breaking strength, it will be considered moderate tension. Crank in 15% of the breaking strength and it is regarded as tight. These figures apply for any diameter of wire. You need only know the wires breaking strength.

Three years ago, in the June 15, 1995 issue, we published a discussion of the views of author Richard Henderson, Skenes Elements of Yacht Design and several riggers, along with an evaluation of an excellent booklet published by Sailsystems about a Selden Mast approach (described in detail in the October 15, 1991 issue) and an entirely new method developed by Michael Dimen, who called his gadget a Rigstick.

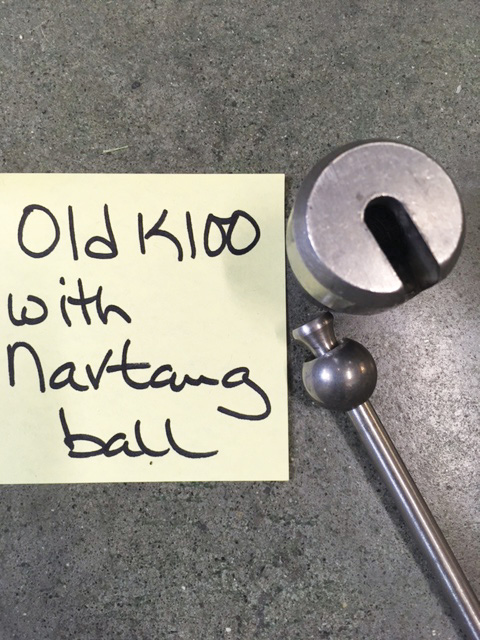

Mentioned was the familiar (see photo) Loos rigging tension gauge, which comes in two sizes. The Model 91 ($39) is for wire 3/32″ to 5/32″. The Model 90 ($45.50) is for 3/16″ to 9/32″. The gauge depends on the bending property of aluminum plate.

The strange-looking gauges don’t willingly produce great accuracy because you have to hold one reading steady while noting another, which also requires that you make a judgment about where the centerline of the wire falls on a scale. Not easy to do.

The big name in galvanized and stainless cable (as wire is called in the trade), cable hardware and tools, Loos & Co., Inc. went looking for a better mousetrap.

Who did Gus Loos go to? The guy who designed the original gauge, his old friend, Donald J. Jordan, an 82-year-old retired Pratt & Whitney engineer who has been sailing out of Marblehead, Massachusetts, in the likes of Lightnings, Friendship sloops, Sound Schooners (which was the prized New York Yacht Club class in 1918), Pearson Wanderers and currently in a 16′ Starling Burgess design, appropriately called a Marblehead.

The old tension gauge wasnt bad, said Jordan. But it tended to get bent. Then the patent ran out and I told Gus we could do a better one.

The new version (see photo) is a distinct improvement over the old aluminum version. A better design, its also much more substantially made of aluminum, stainless and nylon.

The design problems were interesting, Jordan said. A conventional cable tension gauge has two rollers at the ends with a spring-loaded plunger in the middle and a dial gauge to measure the plunger movement. The wheels have to rotate…because they must permit some small but vital movement. That makes the tool expensive. My approach was to have two stationary wheels and a carefully contrived square slider in a arc-slot on the other.

The new Loos gauges use a long-lasting stainless spring to produce the tension. Slip the lower grooved wheels on a shroud or stay, pull the lanyard to engage the upper hook, relax, read the tension at your leisure and consult the scale to learn the pounds of pressure on the wire and the percentage of breaking strength of the wire. There are three wire gauge notches in the edge. The gauge can be left on the wire while turnbuckle adjustments are made.

The accompanying booklet, very well-done, contains a good tight discussion of the subject; some recommendations; a table on how to equalize tension in different sizes of wire, and line-drawn diagrams clearly showing rig tensions (windward and leeward) created by light, medium and heavy winds.

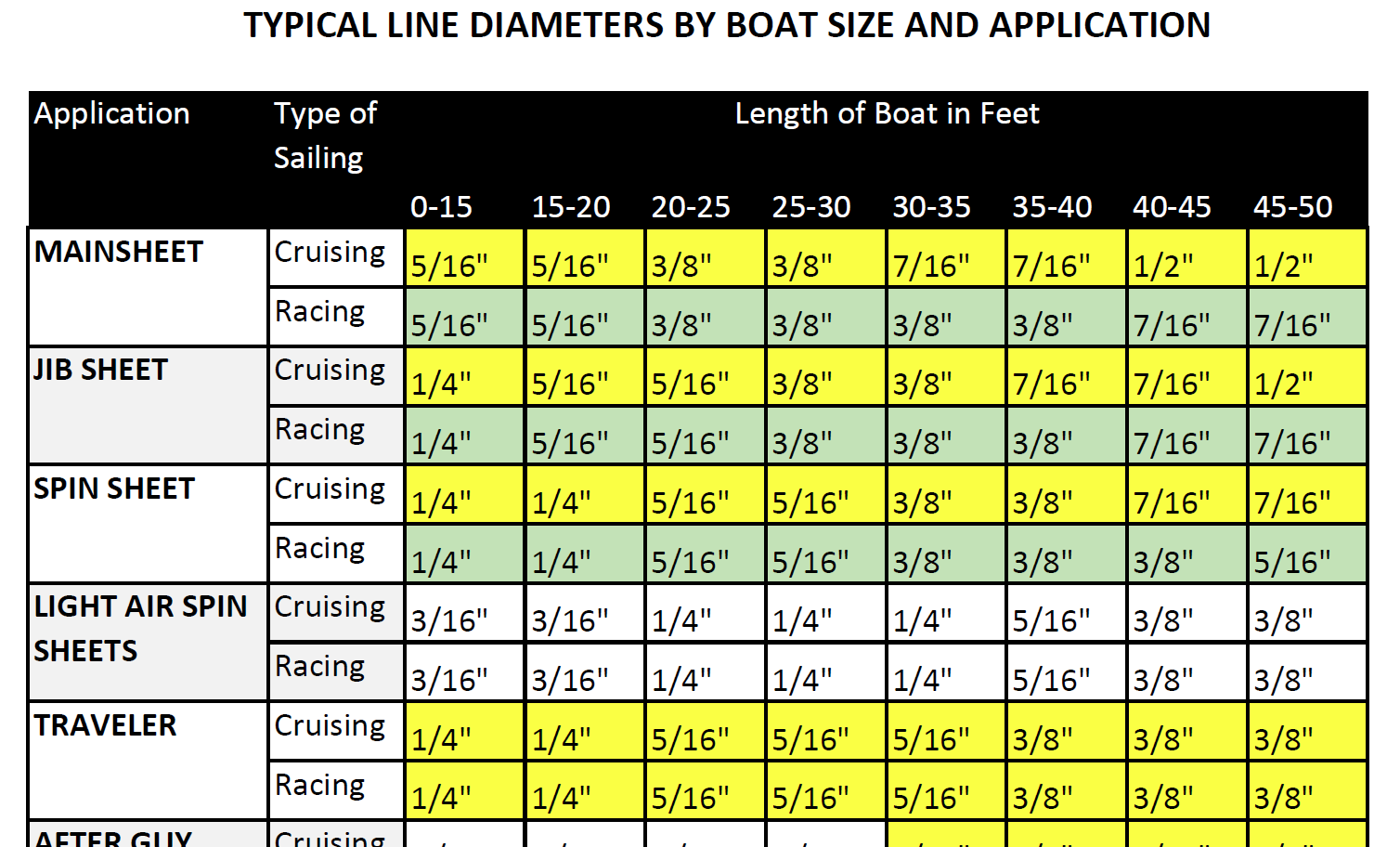

The wire gauge comes in three sizes, for 3/32″-5/32″, 3/16″-1/4″ and 9/32″-3/8″. West Marine sells them, respectively, for $57.99, $69.99 and $$122.99. Defender Industries cuts them to $49.95, $51.95 and $105.95. Prices in the BOAT/U.S. catalog are in between.

What if, instead of 1×19 wire, you have rod rigging? There are four new models that are bigger, heavier and, of course, more costly. They work the same, but take some arm strength. One is for .172-.250 rod, another for .281-.375. Two others models are for metric rod. West Marine sells the rod gauges for $186.99. Neither Defender nor BOAT/U.S. shows them in their catalogs.

Contact- Loos & Co., Inc., 901 Industrial Blvd., Naples, FL 34104, 800/321-5667. Rigstick, 311 Jackson, Port Townsend, WA 98368; 800/488-0855. Sailsystems, PO Box 1218, Marblehead, MA 01945; 978/745-0440.

RELATED ARTICLES MORE FROM AUTHOR

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Log in to leave a comment

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell My Personal Information

- Online Account Activation

- Privacy Manager

We are your Guiding Light.

Boston harbor's premier sailboat rigging and marine systems service company., sailboat rigging and more., marine systems service.

JN Rigging provides sailboat rigging, marine systems and mechanical services to New England's discerning sailors. We specialize in outfitting cruising sailboats for extended offshore passage-making. We strive to create quality rigging and marine systems solutions, blending traditional techniques with modern approach and materials. We also proudly offer the latest in marine energy products, including highly-efficient flexible solar power, hydro-electric generation and lithium-ion battery systems. We aim to help advance yacht systems technology forward to create truly self-reliant and sustainable energy solutions for our customers.

JN Rigging works with a variety of clients and sailing vessels of all shapes and sizes, from the small dinghy sailer to larger high-performance cruising and racing craft. Additionally, we provide sailing product and system design support and consultation to several boat builders and sailing equipment manufacturers. We're always looking for new and interesting ways to apply our knowledge and skills.

Located at the historic Hingham Shipyard, JN Rigging strives to be the trusted resource and purveyor of quality rigging products, service and consultation to the Boston and South Shore sailing communities, and beyond.

Check out our latest projects!

News & updates, check out and subscribe to our blog..

Copyright © 2020 JN Rigging, LLC. All rights reserved.

Standing Rigging (or ‘Name That Stay’)

Published by rigworks on november 19, 2019.

Question: When your riggers talk about standing rigging, they often use terms I don’t recognize. Can you break it down for me?

From the Rigger: Let’s play ‘Name that Stay’…

Forestay (1 or HS) – The forestay, or headstay, connects the mast to the front (bow) of the boat and keeps your mast from falling aft.

- Your forestay can be full length (masthead to deck) or fractional (1/8 to 1/4 from the top of the mast to the deck).

- Inner forestays, including staysail stays, solent stays and baby stays, connect to the mast below the main forestay and to the deck aft of the main forestay. Inner forestays allow you to hoist small inner headsails and/or provide additional stability to your rig.

Backstay (2 or BS) – The backstay runs from the mast to the back of the boat (transom) and is often adjustable to control forestay tension and the shape of the sails.

- A backstay can be either continuous (direct from mast to transom) or it may split in the lower section (7) with “legs” that ‘V’ out to the edges of the transom.

- Backstays often have hydraulic or manual tensioners built into them to increase forestay tension and bend the mast, which flattens your mainsail.

- Running backstays can be removable, adjustable, and provide additional support and tuning usually on fractional rigs. They run to the outer edges of the transom and are adjusted with each tack. The windward running back is in tension and the leeward is eased so as not to interfere with the boom and sails.

- Checkstays, useful on fractional rigs with bendy masts, are attached well below the backstay and provide aft tension to the mid panels of the mast to reduce mast bend and provide stabilization to reduce the mast from pumping.

Shrouds – Shrouds support the mast from side to side. Shrouds are either continuous or discontinuous .

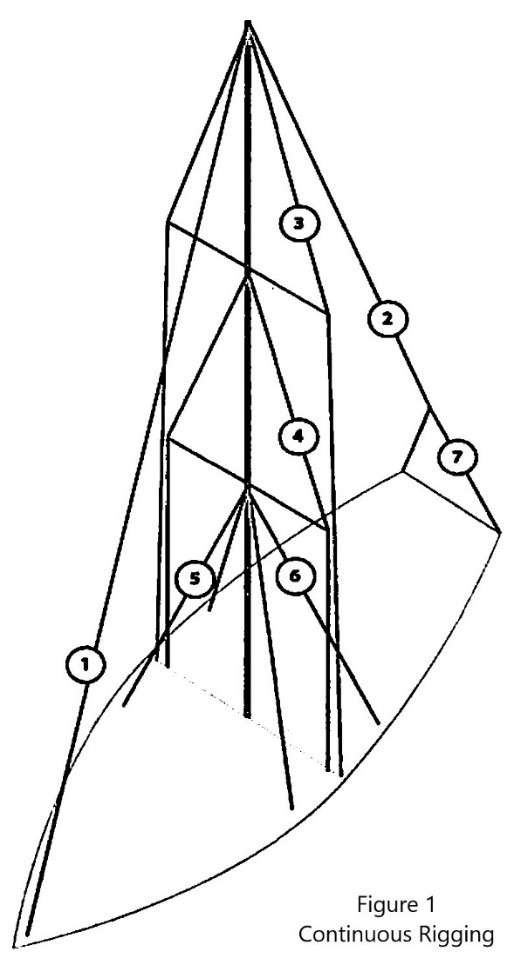

Continuous rigging, common in production sailboats, means that each shroud (except the lowers) is a continuous piece of material that connects to the mast at some point, passes through the spreaders without terminating, and continues to the deck. There may be a number of continuous shrouds on your boat ( see Figure 1 ).

- Cap shrouds (3) , sometimes called uppers, extend from masthead to the chainplates at the deck.

- Intermediate shrouds (4) extend from mid-mast panel to deck.

- Lower shrouds extend from below the spreader-base to the chainplates. Fore- (5) and Aft-Lowers (6) connect to the deck either forward or aft of the cap shroud.

Discontinuous rigging, common on high performance sailboats, is a series of shorter lengths that terminate in tip cups at each spreader. The diameter of the wire/rod can be reduced in the upper sections where loads are lighter, reducing overall weight. These independent sections are referred to as V# and D# ( see Figure 2 ). For example, V1 is the lowest vertical shroud that extends from the deck to the outer tip of the first spreader. D1 is the lowest diagonal shroud that extends from the deck to the mast at the base of the first spreader. The highest section that extends from the upper spreader to the mast head may be labeled either V# or D#.

A sailboat’s standing rigging is generally built from wire rope, rod, or occasionally a super-strong synthetic fibered rope such as Dyneema ® , carbon fiber, kevlar or PBO.

- 1×19 316 grade stainless steel Wire Rope (1 group of 19 wires, very stiff with low stretch) is standard on most sailboats. Wire rope is sized/priced by its diameter which varies from boat to boat, 3/16” through 1/2″ being the most common range.

- 1×19 Compact Strand or Dyform wire, a more expensive alternative, is used to increase strength, reduce stretch, and minimize diameter on high performance boats such as catamarans. It is also the best alternative when replacing rod with wire.

- Rod rigging offers lower stretch, longer life expectancy, and higher breaking strength than wire. Unlike wire rope, rod is defined by its breaking strength, usually ranging from -10 to -40 (approx. 10k to 40k breaking strength), rather than diameter. So, for example, we refer to 7/16” wire (diameter) vs. -10 Rod (breaking strength).

- Composite Rigging is a popular option for racing boats. It offers comparable breaking strengths to wire and rod with a significant reduction in weight and often lower stretch.

Are your eyes crossing yet? This is probably enough for now, but stay tuned for our next ‘Ask the Rigger’. We will continue this discussion with some of the fittings/connections/hardware associated with your standing rigging.

Related Posts

Ask the Rigger

Do your masthead sheaves need replacing.

Question: My halyard is binding. What’s up? From the Rigger: Most boat owners do not climb their masts regularly, but our riggers spend a lot of time up there. And they often find badly damaged Read more…

Selecting Rope – Length, Diameter, Type

Question: Do you have guidelines for selecting halyards, sheets, etc. for my sailboat? From the Rigger: First, if your old rope served its purpose but needs replacing, we recommend duplicating it as closely as possible Read more…

Spinlock Deckvest Maintenance

Question: What can I do to ensure that my Spinlock Deckvest is well-maintained and ready for the upcoming season? From the Rigger: We are so glad you asked! Deckvests need to be maintained so that Read more…

Rod Rigging Replacement Cost: 2023 Breakdown

Although rod rigging is stronger and lighter than wire rigging, over time it can still wear out and need replacement. You can replace the rod rigging on your boat all by yourself, but you still need to spend money on materials and equipment. If you're curious about the overall replacement costs, let's break down how much you need to prepare to replace your rod rigging in 2023 and provide tips for reducing your overall costs.

The cost of rod rigging replacement ranges from $8,000 to $20,000. The cost of materials averages from $5,000 to $10,000, while the cost of labor is between $2,000 and $5,000. Expenses for equipment range from $1,000 to $2,000, while the cost of permits or inspections is estimated to be around $500 to $1,000.

The three types of materials commonly used in rod rigging are stainless steel, nitronic 50 stainless steel, and synthetic rigging. The cost of each material per foot will affect the overall cost of replacing rod rigging. Let's compare the prices of each material per foot.

- You will only need to spend around $6,000–$15,000 for materials and equipment for DIY rod rigging replacement.

- Budget at least $1,000–$2,000 for high-quality equipment to help lower long-term maintenance costs.

- A more experienced professional rigger usually charges a high rate, around $50-$150 per hour, but they may also be able to complete the replacement more efficiently and with higher quality.

- Synthetic rigging is the lightest and strongest option, as well as the one with the highest upfront costs, ranging from $25 - $50 per foot.

- If your boat is valued at $100,000, the estimated insurance cost for rod rigging replacement could be around $1,000–$2,000 (which is around 1-2% of the total value of the boat).

Detailed Breakdown Of Rod Rigging Replacement Costs In 2023

Below are the main cost factors involved in rod rigging replacement:

Account for rod rigging material costs

Rod rigging is typically more expensive than wire rigging, but it is also more durable and can last for about 10–20 years. . The estimated cost ranges from $5,000 - $10,000.

There are several types of materials that can be used for rod rigging replacement, and each comes with different costs:

Stainless steel is known for its strength and durability

Stainless steel is also a popular choice for rigging because it is resistant to corrosion and is relatively easy to maintain. It is often used in cruising boats and is suitable for most sailing conditions. Here's our article about the advantages of using stainless steel for rigging .

Nitronic 50 stainless steel has a higher tensile strength than the regular one

Nitronic 50 stainless steel is a high-performance material that is becoming increasingly popular in the sailing industry because it is more resistant to elongation, corrosion, and fatigue cycling.

It is also lighter and has less windage per foot of wire rigging. As a result, it is often used in racing boats where weight and wind resistance are critical factors. It is also often considered as an alternative material to stainless steel when replacing standing riggings .

Synthetic rigging is made from woven high-strength fibers

Synthetic rigging, such as Dyneema or composite rigging, is a relatively new development in the sailing industry. It is made from high-strength fibers that are woven together to create a lightweight and strong rigging system.

It is often used in racing boats due to its low weight and wind resistance. It is also becoming more popular in cruising boats due to its ease of handling and maintenance. If you're opting for Dyneema as your choice of material, here's how much it can cost.

Factor in the labor costs

The estimated cost range of hiring a professional rigger ranges from $2,000 - $5,000 depending on the hourly rate of the professional and the time required for the replacement. On average, hourly rates for rigging professionals range from $50-$150 per hour.

Now, the time required for rod rigging replacement depends on the size of the boat and the complexity of the rigging system but it can take anywhere from a few days to a few weeks to complete. This includes the time needed to remove the old rigging, install the new rigging, and perform any necessary adjustments and tuning.

Note that some professionals may charge a flat fee for the entire project, while others may charge an hourly rate. Try to get quotes from multiple professionals to compare costs and ensure that all aspects of the replacement are included in the quote.

You might also want to consider the experience level and reputation of the professional hired, as a more experienced professional may charge a higher rate but may also be able to complete the replacement more efficiently and with higher quality.

Take into consideration the cost of equipment

The estimated cost range allotted for equipment is around $1,000 - $2,000. Some common equipment needed includes rigging tools such as wire cutters, swage tools, and turnbuckle wrenches, as well as hardware such as clevis pins, cotter pins, and thimbles.

Perhaps consider the specific needs of the project when selecting equipment, as some boats may require specialized equipment that can increase the cost. Higher-quality equipment may be more expensive, but can also be more durable and reliable, leading to lower long-term maintenance costs. Cheaper equipment may be more affordable, but can also be more prone to breaking or wearing out quickly.

Budget for permits or inspections

Some common permits required may include permits for working in a marina or boatyard, permits for working in a protected or environmentally sensitive area, or permits for working on a historic or landmark vessel. You could research the specific permits required for the location and type of boat before starting the replacement.

Some locations may require inspections of the rigging system after the replacement is complete. For example, some states may require a safety inspection of the rigging system before the boat can be launched. Some permits may also be free, while others may require a fee.

Prepare for insurance costs

A rough estimate for insurance costs could be around 1-2% of the total value of the boat. So if the boat is valued at $100,000, the estimated insurance cost for rod rigging replacement could be around $1,000-$2,000.

If you have insurance for your sailboat , try to check your policy to see if it covers rod rigging replacement. Some insurance companies may cover the cost of replacement if the rigging fails due to normal wear and tear or if it is damaged in an accident. However, some policies may only cover the cost of replacement if the rigging fails due to a specific cause, such as a lightning strike.

If your boat is older and has a lower value, it may not be worth the cost of replacing the rigging. However, if your boat is newer and has a higher value, it may be worth the investment to ensure that your rigging is in good condition.

Recommendations To Reduce Overall Replacement Costs

Below are some tips to cut down on the overall costs of replacing rod rigging:

1. A regular inspection ensures the safety and longevity of your rod rigging

Over time, rod rigging can weaken and become more prone to failure, especially if it is exposed to harsh sailing conditions, which is why regular inspection is needed. In fact, manufacturers recommend replacing the standing rigging at least every 10–15 years.

Regular inspection involves checking the condition of the rod rigging and looking for signs of wear, corrosion, or damage. You can do this inspection yourself or hire a professional to do it for you. If you choose to do it yourself, you may need to have the necessary knowledge and tools to do it safely and effectively.

One way to inspect your rod rigging is to use a magnifying glass to look for signs of wear or corrosion. You should also check the fittings and connections for signs of damage or wear. If you notice any issues, it's important to address them right away to prevent further damage.

Regular inspection can help you catch potential problems before they become major issues. By catching problems early, you can save yourself time and money in the long run. It's much cheaper to replace a few pieces of rod rigging than to replace the entire rigging system.

In addition to regular inspection, you also need to know when to replace your rod rigging. Rod rigging typically has a lifespan of around 8–10 years, depending on factors such as sailing conditions and age. If your rod rigging is approaching this age, it's a good idea to start planning for its replacement.

2. Consider DIY options

The cost of DIY rod rigging replacement depends on the specific needs of the project, but on average, the cost of materials and equipment can range from $6,000-$15,000.

Doing the rod rigging replacement yourself can save you a significant amount of money on labor costs as well as potential equipment rental. It can also be a rewarding and educational experience for boat owners who want to learn more about their rigging system.

However, without proper experience and training, DIY replacement can be dangerous and can result in mistakes that can compromise the safety and performance of the rigging system. Additionally, it may not be covered by insurance, which can be a significant risk in the event of an accident.

Leave a comment

You may also like, what's the life expectancy of rod rigging.

Rod rigging has several advantages over traditional rigging, including increased strength, reduced weight, and improved aerodynamics, which explains why it is …

Average Cost to Replace Standing Rigging (with Examples)

How Often Should Standing Rigging Be Replaced? (Minimally)

Exact Cost To Replace Standing Rigging in Australia

Average Cost of Dyneema Rigging (Different Rig Types)

Own your first boat within a year on any budget.

A sailboat doesn't have to be expensive if you know what you're doing. If you want to learn how to make your sailing dream reality within a year, leave your email and I'll send you free updates . I don't like spam - I will only send helpful content.

Ready to Own Your First Boat?

Just tell us the best email address to send your tips to:

This page is currently offline due to an unexpected error. We are very sorry for the inconvenience and will fix it as soon as possible.

Advice for developers and administrators: Enable debug mode to get further information about the error.

Service Locator

- Angler Endorsement

- Boat Towing Coverage

- Mechanical Breakdown

- Insurance Requirements in Mexico

- Agreed Hull Value

- Actual Cash Value

- Liability Only

- Insurance Payment Options

- Claims Information

- Towing Service Agreement

- Membership Plans

- Boat Show Tickets

- BoatUS Boats For Sale

- Membership Payment Options

- Consumer Affairs

- Boat Documentation Requirements

- Installation Instructions

- Shipping & Handling Information

- Contact Boat Lettering

- End User Agreement

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Vessel Documentation

- BoatUS Foundation

- Government Affairs

- Powercruisers

- Buying & Selling Advice

- Maintenance

- Tow Vehicles

- Make & Create

- Makeovers & Refitting

- Accessories

- Electronics

- Skills, Tips, Tools

- Spring Preparation

- Winterization

- Boaters’ Rights

- Environment & Clean Water

- Boat Safety

- Navigational Hazards

- Personal Safety

- Batteries & Onboard Power

- Motors, Engines, Propulsion

- Best Day on the Water

- Books & Movies

- Communication & Etiquette

- Contests & Sweepstakes

- Colleges & Tech Schools

- Food, Drink, Entertainment

- New To Boating

- Travel & Destinations

- Watersports

- Anchors & Anchoring

- Boat Handling

Inspecting Sailboat Rigging

Advertisement

Here's how to go over your rig with a fine tooth comb.

Sight up the mast. Is it straight?

If there's one thing production sailboats have in common, it's that nearly all of them use stainless-steel standing rigging, whether wire or rod. There are likely also stainless steel fittings, chainplates and turnbuckles. Stainless steel is a great material for rigging but has its Achilles heel: corrosion. Stainless steel in a saltwater environment will eventually suffer from some form of corrosion, whether it's stress-crack corrosion, fatigue cracking or crevice corrosion. Sailboat rigging in freshwater may also suffer from stress and fatigue cracking (see below). What might appear to be a small crack or area of pitting will degrade the fitting by eating away at the metal. Any cracks or corrosion will weaken the fitting, and the failure of a single fitting can bring down a rig.

Stainless Steel Failures

Stainless-steel rigging under heavy stress can have stress cracking or fractures that will often be identified by hairline cracks. These cracks will lead to stress-crack corrosion and crevice corrosion in the saltwater environment.

Crevice corrosion can also develop in areas of pitting when the stainless steel is devoid of oxygen. This is the most common form of corrosion on a stainless-steel chainplate. This chainplate was cut in half to demonstrate how far the pitting went into the metal.

1. Take a look at the overall rig

Sight up the rig from deck level. How is the geometry? All stays and shrouds should be run without any bends and at even angles. Are there hard spots or kinks where a stay has an awkward bend? Standing in front of the mast, sight up from the base. Is the mast in column (straight)? There should be no bends in the mast side-to-side or facing forward. Walk around to all of the shrouds and stays and give them a pull. They all should feel roughly at the same tension. To be accurate, you would want to use a tension gauge. But when I first start inspecting a rig, I'm mostly trying to get a feel if anything appears to be dramatically out of tune.

Left: Inspect swages carefully for corrosion; this swage has broken strands. Right: This crack was only visible after cleaning off the surface rust.

2. Inspect all the deck fittings and wire.

If the mast is deck-stepped, start at the base, looking for corrosion on the step and cracks in the base of the mast. Then working clockwise to make sure you don't miss anything, inspect all fittings from eye level to deck level including swages/mechanical fittings, turnbuckles, chainplates, and toggles. Start with the wire at eye level, and scan downward, checking for rust and broken strands. For rod rigging, we're looking for cracks or corrosion. Take a good look for corrosion where the wire enters the swage or mechanical fitting. Next check the t-bolts, tangs, turnbuckles, and pins. Clean any rust off with the Scotch-Brite pad. This is important: anything more than light rust staining could be an indication of crevice corrosion, which weakens the metal. You may not be able to remove all of the rust, but you do need to see the underlying metal. Use your magnifying glass to look for cracks and pitting on the fitting. The turnbuckles should be straight without any bend to them. Inspect the condition of the threads of the stud. Ensure the turnbuckles have locking pins. Photograph the fittings, especially where you think you have sighted a crack or pitting. Get up close with the camera on the macro setting and make sure that the area of concern is in focus; this is important when you enlarge the photo later.

This chainplate has a crack just above where it passes through the deck.

3. Pay attention to the chainplates.

Inspect the caulking where it enters the deck; it should not be cracked or peeling. Look for cracks in the chainplates on the edges and especially around the pinholes. For external chainplates, inspect along the edges for cracks and rust blooms. A small amount of rust may be OK; it might just be staining, though it should still be investigated. But significant rust is a sign that there may be crevice corrosion, which is a reason to pull and inspect the chainplates. Unfortunately, the area that is probably affected the most is buried and not visible unless the chainplate is removed. Stainless-steel corrosion happens much faster when there is no oxygen present — like where the chainplates pass through the deck, which is why we'll inspect them belowdecks as well.

Look for peeling paint, which may be a sign of corrosion, and cracks at the gooseneck and other boom fittings.

4. Inspect all attachments to the mast and boom on deck and at eye level.

Inspect the gooseneck fitting for the mast and the vang attachment for corrosion or cracks. Any attachment points on the boom for running rigging also need to be inspected. Again, take close-up photos if you find any problems. Check all blocks to make sure they turn freely. All shackles should be secured with seizing wire. The winches need to turn freely and stop when the direction is reversed. Do the line stoppers stop the line? Give the line a good tug with the line stopper closed. There should be no movement. Inspect each piece of the running rigging for wear. What is the condition of the halyard and the safety line (a second halyard) you will use for going aloft? Don't take chances here.

Check for white powder and pitting on aluminum mast steps and at the base of the mast.

5. Inspect the condition of the mast step.

Mast steps here are often in a damp environment, and a lot of mast steps are made from non-stainless steel on older boats, which can rust. Some boats have an aluminum mast step. If the step or base of the mast is corroding, it will have white powder on it. Remove the powder and look for pitting underneath. If you find pitting here, or on any other aluminum fitting, such as the mast or boom, have a rigger follow up with a professional inspection.

Painting chainplates is a bad idea because it hides corrosion. Once rust is visible through the paint, the corrosion is severe, and the chainplate will need to be replaced.

6. Go below to take a look at the chainplates.

Are there signs of water intrusion on the bulkheads? You might have to remove some cover panels to gain access to the chainplates. Are there signs of rust? Clean any rust with your nylon pad. Use a flashlight and your magnifying glass to inspect the chainplate carefully. Pay close attention to the edges of the chainplate for rust and cracks. Cracks and corrosion can develop behind the chainplate and where it passes through the deck. Again, these are areas that are deprived of oxygen where crevice corrosion will develop. Chainplates don't last forever, and if you want to be absolutely sure you can count on them, I'd recommend replacing them after 20 years of service or if there are any signs of crevice corrosion, which can happen in less than 15 years in harsh environments.

Broken wire at swage fitting on a catamaran mast head.

7. If you found no deficiencies then it is time to go up the mast.

If you are not comfortable, then I recommend having a professional rigger conduct the aloft part of the inspection. Never do this by yourself, even if you have a hoist that allows you to do so. Have someone there to assist you and to manage your safety line. For the aloft portion of the inspection, work your way up from the bottom, rather than starting at the top. This way, if you are at the spreaders and find a cracked swage fitting, you can make the decision to stop. This part of the inspection will be conducted in the same manner as the lower fittings and chainplates, this time also paying close attention to where fasteners are installed into the mast. On an unpainted aluminum mast, we are looking for the white powder and pitting which are signs of corrosion and can lead to hairline cracks. Again, if you clean the powder away and find pitting, you'll need to have a professional rigger take a look. On a wooden mast, you're looking for soft wood and discoloration where the fastener goes into the wood. For carbon fiber you're looking for cracks. Inspect the spreader ends and tips for wear and the condition of the boots.

8. Thought you were finished?

Not yet. Now go find somewhere comfortable and view all of your photos on a tablet or computer. Enlarge them to help find any cracks or pitting. This is why you took your photos in order and made notes about what was what. Discuss any of your findings that concern you with a professional rigger. Save all of your photos in a file so you can compare them the next time you do the inspection.

Now that you've done a bottom-to-top rig inspection, you can feel more comfortable the next time the wind pipes up. At the beginning of each season, take an hour or so to re-inspect the rig, focusing on the areas you might have noted to keep an eye on.

Related Articles

The truth about ceramic coatings for boats.