Hundreds of ships go missing each year, but we have the technology to find them

Senior Lecturer in Astronomy, University of Leicester

Disclosure statement

Nigel Bannister works for the University of Leicester. He received funding from US Office of Naval Research - Global to conduct this work.

University of Leicester provides funding as a member of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

The seas are vast. And they claim vessels in significant numbers. The yachts Cheeki Rafiki , Niña , Munetra , Tenacious are just some of the more high-profile names on a list of lost or capsized vessels which grows by hundreds each year.

Yet it took the disappearance of flight MH370, now declared lost with no survivors , to demonstrate how difficult it can be to find something in the open ocean. As the search continued, incredulity grew: exactly how, in the 21st century, is it possible to lose a 64-metre aircraft?

There are great unknowns at sea: planes and boats go missing. Illegal fishing and piracy are easy to conduct – and small vessels can smuggle powerful weapons and dangerous individuals. The technology to improve this situation already exists, we just need to make better use of it.

The view from above

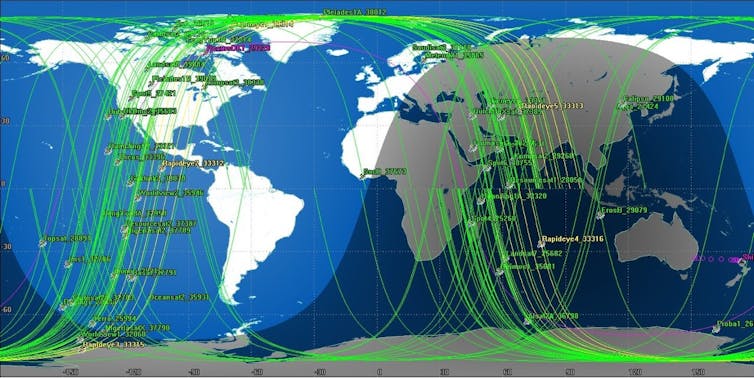

Satellites provide the vantage point necessary to monitor large areas of ocean. Spacecraft carrying synthetic aperture radar (SAR) can provide high-quality images with resolution down to a metre, regardless of the weather. But the relatively small number of spacecraft equipped with SAR, and the dawn-to-dusk orbits which most occupy, also limit the times of day when they can provide coverage.

To offer comprehensive monitoring at sea, we need to bring together different types of imaging, including radar and photographic images in the human-visible wavelength. This is often overlooked for maritime purposes due to the effects of cloud, rain, and darkness that limit its use. But there are enough satellites with the capability that could provide excellent coverage.

Detail and coverage

The two key requirements for effective monitoring are high spatial resolution (good detail) and a large field of view (wide area). One tends to come at the expense of the other, so that a device – whether it is a camera, satellite or radar – capable of detecting small vessels will usually only be able to scan an area a few tens of kilometres wide, making it both unlikely that the search area of interest has been recorded and rendering subsequent searches very slow.

But the situation is changing. The number of imagers is growing rapidly. In our recently published study , we identified 54 satellites carrying 85 sensors which offer useful resolution and could be accessed commercially (excluding military surveillance spacecraft). Companies such as PlanetLabs are in the process of launching many more.

While each satellite’s imaging device generates an image track only 10-100km across, the motion of the satellite as it orbits the Earth effectively “scans” that track so that the image is narrow in one dimension but circles the world in the other. With orbital periods of around 90 minutes, one satellite makes around 16 passes over the daylit hemisphere every day. The combined imaging work of all these satellites now make a significant contribution to our awareness of maritime traffic.

Image early, image often

Imagery used in search-and-rescue operations is usually taken after the target is lost. In the case of the Niña which disappeared off the coast of New Zealand, eight days elapsed between last radio contact and the alarm being raised. For MH370, the search area evolved over periods of weeks. In both cases, ocean currents carry evidence away from the accident site, while debris disperses and sinks, making it more difficult to identify by satellite.

It would be far better to have an archive of recent, regularly updated images so that the recent history of a location over a period of several days can be examined. This could offer evidence of the vessel’s course or state, or pick up on areas of fresh, concentrated debris.

Making the best of what we have

Satellites with visible wavelength cameras are generally used for gathering images of land. What if satellite operators could generate revenue by taking images of the oceans? The limited resources on satellites mean that it isn’t generally possible to constantly take images, to store that data and transmit it all in the next available contact with the ground (which may be some time after an image is acquired). As it is, it’s not possible to create a global maritime monitoring system of this kind without purpose-built spacecraft with bigger data storage and more frequent contact with ground stations to download it.

But it is possible to monitor high-priority areas of heavy traffic, protected fisheries and security-critical regions, with co-operation between operators of existing spacecraft (for which there are precedents such as George Clooney’s Satellite Sentinel Project , which uses satellites to gather evidence of atrocities and war crimes), and incentives, perhaps involving maritime insurance companies.

Retrieving hundreds of gigabytes of data a day from satellites requires a new approach to ground stations. One solution may be to “crowdsource”: to create a network of stations operated by small institutions, universities and individuals to spread the burden of downloading data and increasing the periods during which data can be recorded and transmitted.

There are groups working on automated vessel-detection algorithms – and crowdsourcing also has a role here, such as TomNod , for example, which asked members of the public to help inspect images online in the search for Niña. How much more effective could search and rescue be if the power of crowdsourcing was applied to each stage of data acquisition, storage and processing, combined with high-quality images taken around the time the vessel was lost?

- satellite tracking

- Missing aircraft

- Search and Rescue

- Maritime security

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

Senior Disability Services Advisor

Deputy Social Media Producer

Associate Professor, Occupational Therapy

GRAINS RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION CHAIRPERSON

Insurance: The Basics

- About the Industry

- Auto Insurance

- Homeowners + Renters Insurance

- Life Insurance

- Financial Planning

- Business Insurance

- Disasters + Preparedness

- Thought Leadership

- Other Insurance Topics

- Research + Data

- Catastrophes

- Crime + Fraud

- Insurance Industry

- Life + Health

Resource Center

- Resilience Accelerator

- Event Calendar

- I.I.I. Glossary

- I.I.I. Store

- Latest Studies

- Presentations

- Publications

- The I.I.I. Insurance Blog

- Video Library

- Learn More About Membership

- Register for a Member Account

- Learn More About Amplify

EN ESPAÑOL

- Conceptos Básicos de Seguros

Connect With Us

- Popular search terms

- Home + Renters

- Popular Topics

- Disaster + Preparation

Popular Media

Please sign in to access member exclusive content.

Forgot Password?

Don't Have an Account? Register Now

Learn more about membership

Facts + Statistics: Marine Accidents

In this facts + statistics, global shipping losses by number of vessels, 2013-2022 (1), global shipping losses by number of vessels by region, 2013-2022 (1).

- DOWNLOAD TO PDF

There were 38 large ships totally lost in 2022, a decline from 59 in 2021, according to latest data from Allianz. Safety & Shipping Review 2023 reports improvements in maritime safety have been significant over the past 10 years.

The region encompassing South China, Indochina, Indonesia and the Philippines had the largest number of shipping losses in 2022 with a total of 10. The region has ranked first in shipping losses over the past decade.

(1) Total losses, vessels over 100 gross tons.

Source: Allianz Commercial, Safety and Shipping Review 2023. Copyright © 2023.

View Archived Tables

NA=Data not available.

Back to top

What’s Wrong With All the Ships?

Do recent boat disasters actually point to a global shipping industry in distress?

Are the boats okay?

They seem to be in a tough stretch. A ship called the Felicity Ace is currently afire and adrift in the Atlantic Ocean, off the Azores, with a reported 4,000 cars on board, including Porsches, Bentleys, and Audis. The crew abandoned the vessel, en route to the United States, last week, and firefighters are now trying to control the blaze.

In January, a different container ship, the Madrid Bridge, limped into the port of Charleston, South Carolina, after losing about 60 containers at sea. Pictures of the vessel showed one row of the metal boxes collapsed and teetering over the gunwale. Among the cargo lost : highly anticipated print runs of cookbooks from Mason Hereford and Melissa Clark.

A week later, an oil-storage vessel exploded off the coast of Nigeria. Within days, a Mauritian oil tanker had run aground off Reunión in the Indian Ocean. In Peru, workers are still cleaning up a spill that, according to some accounts, occurred when a tanker was rocked by tsunami waves. Experts are nervously watching another tanker off the coast of Yemen, which is slowly disintegrating in the midst of a war and an existing humanitarian crisis.

These cases come just months after the spectacle of the Ever Given, a massive container ship that wedged itself into the banks of the Suez Canal, halted shipping for days, and enthralled a world bored to tears with the pandemic. These incidents are transfixing—a little awesome, in the old-fashioned sense , and a little hilarious, in a very contemporary internet-ironic one —but is the global shipping industry in some sort of collapse?

Read: The big, stuck boat is glorious

The short answer is no. “It’s just that people have noticed,” John Konrad, the CEO of the shipping site gCaptain , told me. Over the past few years, about 50 major ships have been lost annually. (Comprehensive figures from 2021 are not available yet, but Konrad said he doesn’t see evidence of any big jump last year.) Most of the time, the public has no reason to pay attention to these sinkings and collisions. But supply-chain crunches caused by the pandemic have made the shipping system more visible than it has been for decades, spotlighting cases like the Felicity Ace and Madrid Bridge. Meanwhile, more volatile weather caused by climate change and ever-larger container ships mean the risk of losses may be rising.

Until recently, major nautical disasters could seem like a relic of the past, like train wrecks or dirigible crashes. Every year, the German insurance giant Allianz issues a report on shipping and safety, and it captures steady improvement. As recently as 2000, more than 200 big ships were lost. (Don’t call them “boats” unless you’re ready to be corrected by cranky old salts.) By the early 2010s, that number had dropped to about 100 a year. In 2021, just 49 were lost, and 2020 saw only 48 losses. Allianz attributes this to “the positive effect of an increased focus on safety measures over time, such as regulation, improved ship design and technology, and risk management advances.”

Even so, that’s a startling rate of one major ship lost almost every week. Most of them don’t make the news. Though classified as “major,” most of these ships are far smaller than the Ever Given or the Felicity Ace. Their crews also largely comprise seafarers from countries like the Philippines or India, the ships sink far away (the biggest portion of losses is around the South China Sea), and their cargo isn’t something that Americans consumers miss. But when ships laden with things Americans care about, such as cars and cookbooks, start hitting choppy seas, they tune in.

In 2015, the cargo ship El Faro sank in the Atlantic Ocean with American sailors on board—a rare loss from the shrinking U.S.-flagged fleet. The Ever Given snarled Suez Canal traffic headed to Europe, affecting Western consumers and becoming a somewhat blunt metaphor for supply-chain disruptions affecting all kinds of goods. The Felicity Ace was bound for Rhode Island when it caught fire, carrying luxury cars for the U.S. market. One Porsche on board was being shipped to the editor of a popular car-review site .

Even under these circumstances, a major disaster doesn’t always make much national news. In September 2019, a car carrier called the Golden Ray, roughly the same size as the Felicity Ace, capsized in St. Simons Sound off Georgia. No cargo ship so large had sunk in U.S. coastal waters since the Exxon Valdez, and the process of breaking up the ship—one of the most expensive salvage efforts in history—concluded only in October. Outside of the trade and regional press, however, the story barely made a splash.

The pandemic could be a factor in some of these recent accidents. Every link in the supply chain, from truckers to ports to shipboard crews, is subject to strain and fatigue. When the freighter Wakashio grounded off Mauritius in 2020, two crew members had been on board for more than a year, prevented from normal rotations onto shore and trips home because of quarantine rules.

Derek Thompson: America is running out of everything

But two problems do seem to be growing: shipboard fires and containers going overboard, like the ones that sent the cookbooks to a watery grave. The reasons have nothing to do with the pandemic. First, the size of vessels continues to grow, though the crews in charge of wrangling them stay the same size. The Ever Given was one of the largest ships in the world when it launched, at 20,000 20-foot equivalent units (TEUs), a benchmark for container ships. One factor in its grounding was that the huge wall of boxes on board effectively acted as a sail, allowing the wind to drive the ship into the canal’s bank. But ships as large as 24,000 TEUs will soon join the fleet.

“Vessel size has a direct correlation to the potential size of loss,” Allianz notes. “Car transporters/RoRo and large container vessels are at higher risk of fire with the potential for greater consequences should one break out.”

Second, ships are also at greater risk of losing containers, or even sinking, when they hit unexpected storms. Climate change means that rather than being confined to specific seasons, storms can hit at any time. “The weather is getting more unpredictable, and these ships are getting bigger, so they’re stacking higher,” Konrad said. “When the ships get hit in a wave, you get a bigger lever that’s pulling the containers over.” (In a bitter environmental irony, the Felicity Ace fire has kept burning because of lithium-ion batteries on electric cars .) In other words, the recent rash of high-profile shipping snafus may be only a factor of greater attention—but a warming planet means a mounting number of disasters might be just over the horizon.

- Subscriptions

Grab a Seat at the Captain’s Table

Essential news coupled with the finest maritime content sourced from across the globe.

Join our crew and become one of the 105,897 members that receive our newsletter.

A photo shows the ONE Apus as it arrived into view in Kobe, Japan, December 8, 2020, after losing more than 1,800 containers in the N. Pacific Ocean. Photo: Twitter @mrnkA4srnrA

Survey Shows Worrying Increase in Number of Containers Lost at Sea

Share this article.

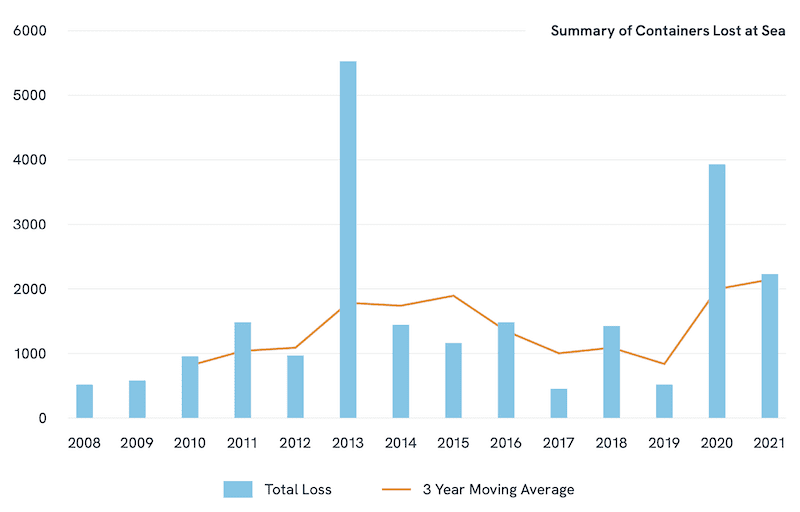

The number of shipping containers lost at sea has risen significantly during the pandemic thanks to an “unusually high” number of incidents particularly in the winter of 2020-21, the World Shipping Council said in its lastest Containers Lost at Sea report.

The winter of 2020-21 saw a huge spike in the number of weather-related incidents , bringing average losses for the two-year period (2020-2021) to 3,113 containers, compared to 779 in the previous period (2017-2019). The past two years caused worrying break in the downward trend for losses, with the average number of containers lost at sea per year since the start of the survey increasing by 18% to 1,629 (from 2008-2021).

The WSC, the main trade association representing the international liner shipping industry, issues its container loss report typically every three years based on surveys with WSC member companies for the preceeding three years. The WSC’s report is viewed in the industry as being the most accurate and official tally of containers lost at sea.

The WSC has conducted previous surveys in 2011, 2014, 2017, and 2020. However, due to the unusually high number of incidents in 2020-21, it’s increasing its frequency of updates to yearly, while its latest report covers the two year period ending in 2021.

The increase in 2020-21 can be attributed to significant container loss incidents, including the ONE Apus which lost more than 1,800 containers in severe weather in November 2020. The Maersk Essen also experienced severe weather in 2021 that resulted in the loss of some 750 containers overboard.

Granted, the number of containers lost at sea can vary widely due to significant incidents such as the two mentioned above. However, such large losses from single incidents have not been reported since the 2014-2016 period, which included the loss of the SS El Faro. There were also significant incidents in 2011, when the grounding of the MV Rena resulted in the loss of about 900 containers, and in 2013, when the MOL Comfort sank in the Indian Ocean with 4,293 containers—the single worst container loss incident on record. The two incidents quadrupled the annual average to 2,683 per year in the period (2011-2013) compared to the 2008-2010 period when just 675 containers were lost at sea each year on average.

Although so far in 2022 there have been few incidents involving containers lost at sea, the industry is “deeply concerned” by the rising numbers.

“Container vessels are designed to transport containers safely and carriers operate with tight safety procedures, but when we see numbers going the wrong way, we need to make every effort to find out why and further increase safety,” says John Butler, President & CEO of WSC.

According to the WSC, international liner carriers’ managed 6300 ships in 2021, carrying goods valued $7 trillion in approximately 241 million containers. The latest Containers Lost at Sea Report covering 2020-2021 shows that containers lost overboard represent less than one thousandth of 1% (0.001%)—a drop in the bucket compared to the total number of containers carried each year.

Improving Safety

Triggered by these events, maritime stakeholders across the supply chain have initiated the MARIN Top Tier project to enhance container safety, with WSC and member lines among the founding partners. The project will run over three years and will use an array of data and scientific measurements to develop and publish specific, actionable recommendations to reduce the risk of containers lost overboard.

For example, initial results from the study show that parametric rolling in following seas is especially hazardous for container vessels, a phenomenon that is not well known and can develop unexpectedly with severe consequences. To help in preventing further incidents a Notice to Mariners has been developed, describing how container vessel crew and operational staff can plan, recognize and act to prevent parametric rolling in following seas.

“The liner shipping industry’s goal remains to keep the loss of containers as close to zero as possible. We will continue to explore and implement measures to make that happen and welcome continued cooperation from governments and other stakeholders to accomplish this goal,” said Butler.

Going forward, the project will continue reporting on progress and sharing insights on a regular basis through the IMO and other forums.

The WSC and member companies have also actively contributed to and supported revision of the IMO’s guidelines for the inspection programs for cargo transport units, as well as the creation of a mandatory reporting framework for all containers lost at sea – an issue that will be on IMO’s agenda in September (CCC 8).

Unlock Exclusive Insights Today!

Join the gCaptain Club for curated content, insider opinions, and vibrant community discussions.

Be the First to Know

Join the 105,897 members that receive our newsletter.

Have a news tip? Let us know.

Stay Ahead with Our Weekly ‘Dispatch’ Email

Dive into a sea of curated content with our weekly ‘Dispatch’ email. Your personal maritime briefing awaits!

Related Articles

Baltimore Bridge Wreck Removal: Progress Report

April 11, 2024: Container Removal Continues The Unified Command is continuing to remove containers from M/V Dali and clear wreckage at the Key Bridge incident site. As of April 11,...

Gard Reports a Surge in Mooring Line Incidents

Maritime insurer Gard says it has observed a rising number of mooring line incidents, particularly during high winds. Gard reports that in several recent cases, wind speeds exceeded 80km/h (equivalent...

NTSB Chair Homendy Provides Update on DALI-Francis Scott Key Bridge Investigation

National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) Chair Jennifer Homendy has provided an update on the board’s ongoing investigation into the M/V Dali incident and the collapse of the Francis Scott Key...

Why Join the gCaptain Club?

Access exclusive insights, engage in vibrant discussions, and gain perspectives from our CEO.

OUT AT SEA?

We’ve got you covered with trusted maritime and offshore news from wherever you are.

JOIN OUR CREW

Maritime and offshore news trusted by our 105,897 members delivered daily straight to your inbox.

Your Gateway to the Maritime World!

Join our crew.

Privacy Overview

- Loss Prevention

- Maritime Health

Idwal: Huge gaps between commitments and reality on crew welfare

US and UK impose sanctions on Iran over drone attack on Israel

ReCAAP ISC: 26 armed robbery incidents against ships in Asia since January

Sixteen major industry organizations ask for safe transit of vessels

- Intellectual

Book Review: The six pillars of self-esteem

American Club: Knowing the ropes of mental health at sea

Good communication is key to solving difficult issues

SEAFiT Barometer Survey: Promoting a healthy lifestyle is a key priority in wellness strategy

- Green Shipping

- Ship Recycling

ABS and USDOE sign MoU to develop clean maritime energy

Singapore, IEA join forces to drive maritime decarbonisation and digitalisation

Singapore leads the way in maritime decarbonisation and digitalisation

Singapore to supply 1 million metric tons of methanol by 2030

- Connectivity

- Cyber Security

- E-navigation

- Energy Efficiency

- Maritime Software

Watch: Partners successfully trial remote-controlled scraping robot for wood-chip carriers

BSM launches Smart Academy for seafarers

PIL partners with DCSA to enhance digitalization standards in container shipping

YGT and EPS ink deal for electric vessel trials

WSC looking to correct FMC contradiction

Egypt detains gas carrier after grounding

New USCG examination program to verify engine room fire safety

China MSA’s action plan to prevent equipment failure

- Diversity in shipping

- Maritime Knowledge

- Sustainability

SEA Europe advocates for a strong maritime industrial strategy

ING: Conflict threatens shipping of oil in Hormuz

Port of Rotterdam throughput declines amidst shifting trade patterns

Protecting Blue Whales and Blue Skies program reaches record participation

Cultivating a supportive and effective environment of psychological safety

Empowering seafarers: How digitalization is shaping maritime recruitment

UK Chamber of Shipping: A clear CII framework can drive industry to adopt effective energy efficiency measures

Trending tags.

- Book Review

- Career Paths

- Human Performance

- Industry Voices

- Maritime History

- Regulatory Update

- Seafarers Stories

- Training & Development

- Wellness Corner

3,174 maritime casualties and incidents reported in 2019

Above image is used for illustration purposes only

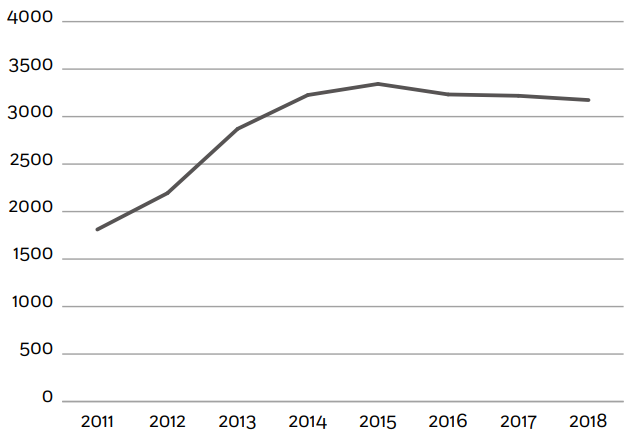

EMSA released its annual review of maritime casualties reporting the total of 3,174 casualties and incidents, highlighting that in the last 5 years the average number of marine casualties or incidents recorded in EMCIP is 3239; The number of very serious casualties has been steady over the last five years.

Overall, 2017’s maritime casualties were a total of 3,301, whereas in 2018 EMSA reported of a decrease in marine casualties, in comparison to the previous year.

The report is based on statistics on marine casualties and incidents that: involve ships flying a flag of one of the EU Member States; occur within EU Member States’ territorial sea and internal waters as defined in UNCLOS; or involve other substantial interests of the EU Member States.

Key numbers 2018

Related News

- 3,174 total incidents and casualties;

- 95 very serious casualties

- 53 fatalities

- 941 injured persons

- 25 ships lost

- 3515 ships involved

- 188 investigations

Accordingly, the total number of reported marine casualties and incidents is 23, 073. In the last 5 years, the average number of marine casualties or incidents recorded in EMCIP is 3,239.

Yet, the report informs that under-reporting of marine casualties and incidents continues, achieving an overall of 4,000 occurrences per year being a best estimate.

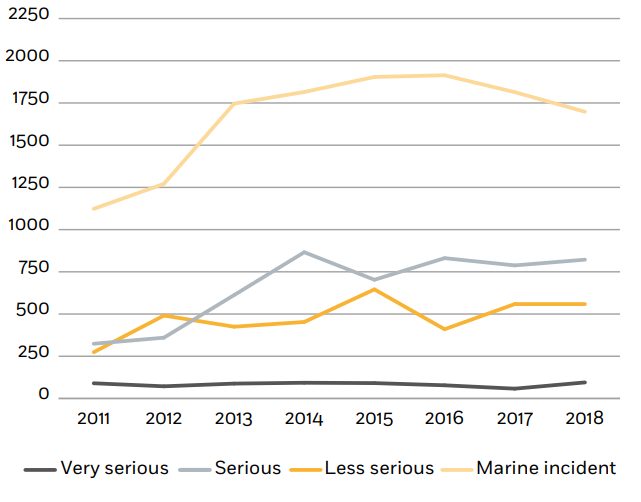

- Very serious casualties:

The number of very serious casualties has been steady over the last five years. However, in relation to the average of the last 5 years an increase of 14.5% in 2018 was noted. Serious casualties increased by 2.5% in 2018.

In 2018, 3.0% of the reported marine casualties were very serious (95), 25.9% serious, 53.5% less serious and 17.6% were marine incidents.

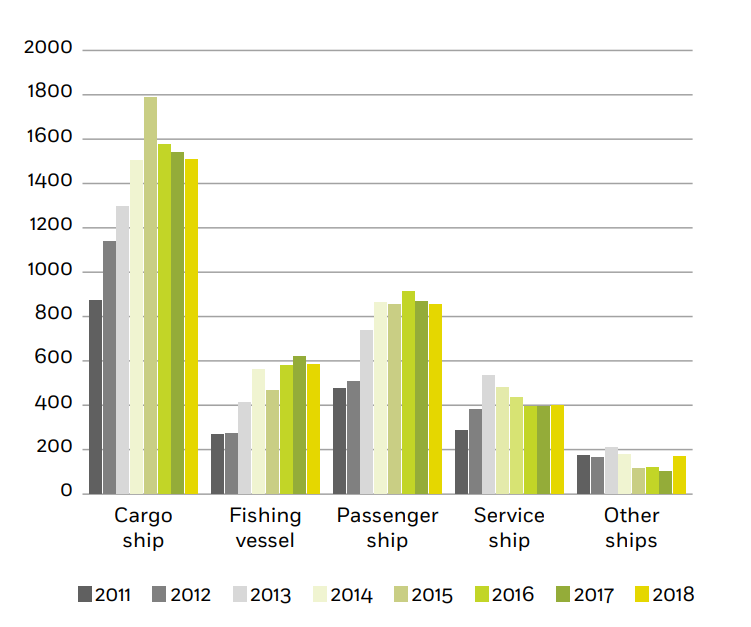

- Casualties by ships:

In the 23,073 marine casualties and incidents that happened from 2011 to 2018, the total number of ships involved was 25,614.

# General cargo ships were the main category involved in a marine casualty or incident (43.8%), followed by passenger ships (23.7%).

In 2018, the number of ships involved in a marine casualty or incident stabilised or slightly decreased in all ship categories, except other ships. The number of other ships involved increase almost 63.7% compared with 2017.

According to EMSA, the distribution of the occurrence severity for the ship is very similar for cargo ships, passenger ships and service ships.

The rate of less serious casualties for fishing vessels is significantly low , more than 10% less, in comparison to other ship categories, indicating that under-reporting is usual in this category.

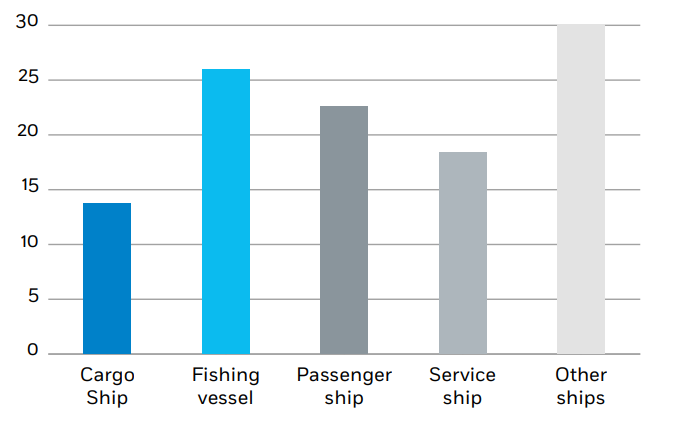

- The youngest category of ships involved in marine casualties was cargo ships with 13.7 years average.

- The oldest was ‘otherships’ with 30.1 years, as expected, considering that this category includes historical vessels.

- Marine casualties

#1 15, 612 occurrences were reported with a ship and 7,461 occurrences with person(s) were recorded.

#2 The ratio 2/3 to 1/3 between occurrences with ship(s) and occurrence with person(s) has remained stable from 2011 to 2018.

#3 In 2018 there was a slight decrease of the casualties or incidents with a ship.

#4 From 2011 to 2018, 2.3% of casualties with a ship were very serious, 21.9% serious, 55.8% less serious and 19.9% marine incidents.

#5 The navigational casualties represent more than (54.4%) of the casualty events, with collisions (26.2%), contacts (15.3%) and grounding/stranding (12.9%

- Root causes of casualty/incident

The investigators looked for the root causes of the casualty, resulting to:

From a total of 4,104 accident events analysed during the investigations, 65.8% were attributed to a human actions’ category and 20% to system/ equipment failures.

In the meantime, Shipboard operations represented the main group with 65% of the total , with 2,003 related to the accident event “Human action”.

Over the 2011-2018 period, 426 accidents led to a total of 696 lives lost, with a very significant decrease since 2015 which was however somewhat reversed in 2018. .

With 566 fatalities, crew is the most affected category of persons.

To explore more, click on the PDF herebelow

The winners of the first SAFETY4SEA – EUROPORT Awards announced

Maersk to upgrade drilling rig into low-emission hybrid.

ABS completes study for USA-Singapore green corridor

NGO Shipbreaking Platform: 127 ships were dismantled from January to March 2024

ReCAAP ISC: Four incidents of armed robbery 9 – 16 April

Insights into American Ports’ readiness and challenges to meet decarbonization demands

UK P&I Club: Understanding and adhering to laws for flying the Chinese National Flag

DNV: Singapore will remain the leading maritime city for the next five years

The report is useful, it will add something to my Thesis

Is it true that more ships are lost while at anchor than at any other situation – or is that an old myth? Do you know where one can find statistics on this? Thanks

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Explore more

- SAFETY4SEA Events

- SAFETY4SEA Plus Subscription

Useful Links

- Editorial Policies

- Advertising

- Content Marketing

© 2021 SAFETY4SEA

- PSC Case Studies

- Tip of the day

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Worse things still happen at sea: the shipping disasters we never hear about

Eight missing from a cargo ship that sank in the Pentland Firth, another grounded near Southampton – these local accidents remind us that the ocean is the most dangerous workplace on the planet. So why do 2,000 seafarers die each year, and what can be done to make them safer?

I take poorly to planes. I am a nervous, panicked and unsettled passenger. In the worst moments, I take Valium, and perhaps – inadvisably – a drink, too. I sit in my seat trying not to grip things too obviously, saying my mantra as the plane rocks through turbulence: “Pretend it’s a ship. Pretend it’s a ship.” I tell myself that the air is water, and that ships rock constantly on water, so what’s the difference? Sometimes it works.

I am terrified of planes, but calm on ships. I spent five weeks on a container ship and only felt unsafe when it was in pirate waters. I was on a huge metal object, buoyant on water, operated by the latest technology and highly trained seafarers. I felt safe.

But given the past two weeks, perhaps I need a new mantra. Last year ended badly, with the fire on the ferry Norman Atlantic and at least 13 dead (not including the inevitable stowaways), and this year has already been deadly: the small cement carrier Cemfjord, carrying a cargo of cement, seven Polish crew and one Filipino, sank in the Pentland Firth near Shetland . Its crew are missing. Hoegh Osaka, a car carrier, was stuck for days on a sandbank off Southampton , after its captain and harbour pilot decided to ground the ship when she began listing alarmingly on leaving port. This was unfortunate, but actually good seamanship: it saved the day, and lives, and prevented pollution.

Even so, the public has reacted to this news with surprise, as they did with Costa Concordia . What, ships sink? But they do, and too frequently. Away from the Pentland Firth and the Solent, away from cameras and attention, five other ships have come to calamity in the first two weeks of this year. Sea Merchant, Araevo, Better Trans, Bulk Jupiter and Run Guang 9. Sea Merchant was a general cargo ship that was travelling from Bauan Port to Antique when it sank after its cargo of cement shifted suddenly , tipping the ship to a dangerous degree in heavy swells. Chief engineer Almarito Anciano died. Araevo, a Greek-owned oil tanker, was bombed by the Libyan air force while moored in the eastern Libyan port of Derna for “acting suspiciously” (although it was actually chartered by the local power station). Casualties: two crew, one Greek and one Romanian. General cargo ship Better Trans foundered in heavy weather in the Philippine sea. The Run Guang 9 had an explosion on board off Guangdong; two crew are missing. Worst, in this dismal roll-call: Bulk Jupiter , a bulk carrier travelling from Malaysia to China with a cargo of bauxite, which capsized off Vietnam. Eighteen of the 19-strong crew died.

These sinkings, fires and bombings are reported, but only in the trade press or – when Filipinos are involved, as they often are, since they provide 25% of world crews – in Filipino media . But they are there, if we look, because ships sink and founder and crash. They sink more in the bad weather of winter, whether gales off Shetland or swells and monsoon rain in the South China sea, where most ship casualties occur. In 2013, according to the World Casualty Statistics published by trade publication IHS Maritime, there were 138 “total losses” – that is, when a ship is beyond repair or recovery. According to John Thorogood, a senior analyst at IHS Maritime, 85 of those were sinkings, “in that the vessel actually went at least partially below the sea in a fairly traumatic manner”. On average, two ships a week are lost, one way or another. That doesn’t take into account smaller vessels or fishing craft.

This is the nature of shipping. The ocean is the most dangerous workplace on the planet. Commercial seafaring is considered to be the second-most dangerous occupation in the world; deep-sea fishing is the first. Each year, 2,000 seafarers lose their lives. The troubles of Cemfjord and Hoegh Osaka were only unusual because of where they happened, which is near enough to the UK mainland to be noticed by the mainstream press.

Cruise ships and passenger ferries attract more attention, because we know them better. They are often our only encounter with the sea as a place of industry: usually the ocean, and the people who work on it, transporting 90% of world trade, is nothing more than some blue on an inflight airline map, to be flown over, hopefully. Commercial shipping is more removed from us now than at any time in history. Ports have been moved out of cities to cope with bigger ships; seafarers are no longer British, western European or American, but Filipino, Polish, Romanian and Indian, as were those who died in the January calamities. That’s just the way globalisation labour pools work.

Even so, shipping is safer than it has ever been. The number of total losses per year has been falling for decades. There are, the International Maritime Organisation calculates, more than 85,000 working vessels (of over 100 gross tonnage) on the seas, so the loss of fewer than 200 is just an inevitable toll of working at sea. It is safer, and it is cleaner, too. Between 1972 and 1981, there were 223 major oil spills. Over the last decade, there were 63.

“Despite last month being a difficult one for the shipping industry,” says Thorogood, “I would say it is more a statistical blip than an indication that safety standards are slipping or any other such inferences.”

Plenty would disagree with him, though, including me. Glen Forbes, who runs the maritime intelligence agency Oceanus Live , suggested the following list of systemic troubles: “Seafarers’ safety and security is compromised by poor safety standards, old and decrepit vessels, unscrupulous owners, blacklisted flag registries, and even near-slavery on fishing vessels.” That’s without endemic piracy, or ghost ships: rust buckets usually sold for scrap value that are instead turned into migrant vessels for desperate Syrians, Eritreans and other people spat out of their country by war or desperation, then abandoned by the minimal crews to drift and be rescued – hopefully – by the nearest coastguard. This is a deliberate tactic that relies on the requirement laid out in the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) document , part of a raft of laws governing the high seas, whereby seafarers are expected to attend to anyone or any vessel in distress on the seas.

And they do: in every accident report, whether a sinking ship, a distressed ferry or a daft yachter, there is usually a merchant vessel coming to its rescue, even now that crews are under enormous pressure to stick to schedules and routes because of the pressure of just-in-time globalisation. Shipping, and containerisation, has given us our cheap T-shirts and our televisions, but at a cost. Even the biggest ships now operate with crews as small as 13. The shortfall is supposed to be taken up by automation, which is one worry. “So many experienced professionals,” wrote former Lloyd’s List editor Michael Grey recently, “have expressed their concern about overreliance on these clever machines, and a generation of computer-savvy officers who fail to look out of the window at the crucial moment.”

A greater problem is fatigue: working seafarers tell me they are routinely knackered because there are no longer enough crew on board. “Safe manning” certificates are part of the oceans of documents that modern ships and masters must carry on board, but Branko Berlan of the International Transport Workers Federation thinks this inadequate. The size of modern crews, he says, “is not about safety, but about commercial pressures”. Crew wages are the easiest thing to cut.

I don’t know why Cemfjord sank. Maybe the crew was exhausted. Maybe the dry cement powder shifted too quickly. Maybe it was a straightforward swamping by atrocious waves. But 60% of ship accidents are due to errors made by what the industry curiously calls “the human element”, and much of that is due to fatigue. As for Hoegh Osaka, the senior national secretary of Nautilus, the UK seafarers’ union , told the BBC that “vehicle and livestock carriers are built to the edge of safety for commercial reasons”. Built to maximise cargo capacity, they go against good naval architecture principles, say critics, and can lose stability far too easily.

Because the Cemfjord and Hoegh Osaka events happened in or near UK waters, I won’t have to wait too long for answers, as they will be immediately investigated by the Maritime and Coastguard Agency and the Marine Accident Investigation Branch. That is often not the case, because of how shipping works. Nearly 70% of the global fleet now flies a flag that often has nothing to do with the ship, the route, the crew or the owner. Open registries, or flags of convenience, allow owners to pay fees to a foreign state, fly its flags and then be governed by the laws of that state while on the high seas. (I’m baffled by cruise passengers who carefully check where they can store their valuables but never check the flag their ship is flying, even though that flag would be responsible for investigating anything that goes wrong.)

Investigations are up to the flag state, and there is no higher authority to push them into publishing accident reports. There are many good flags who do this promptly. Then there are others. I don’t even mean the dreadful ones such as Tanzania, North Korea or Mongolia, increasingly found flying on the migrant ghost ships. What of Danny FII, a livestock carrier flying the flag of Panama, the largest ship registry in the world? In 2009, it sank off Lebanon with its crew of 76, six passengers, 17,932 cattle and 10,224 sheep. The captain, a Scot named John Milloy, went down with his ship; 11 other crew were definitely lost, and 32 crew are still unaccounted for. I was intrigued by it, especially after discovering a forum on a site named Uglyships that, in a quirk of modern technology, had become the most popular meeting place for relatives and former crew.

Why did Uglyships become a meeting place for grieving and desperate relatives? Because, like many other relatives of crew who sailed on Danny FII, they had been given no answers. Compare this to a plane crash, when resources and attention rush to the crash site. Of course, that’s because planes carry people, and more than cargo ships. (Cargo plane crashes rarely get such assiduous attention.) It’s because planes are how we travel now.

A few days after Danny FII sank, Ethiopian Airlines flight ET409 crashed into the same sea. Everyone on board was killed. International aviation rules require accident investigation authorities to make an accident report publicly available “as soon as possible and, if possible, within 12 months”. Posting on the internet is acceptable. I tested these guidelines: the accident report into ET409, although it is disputed by Ethiopian Airlines, was published by the Lebanese authorities in January 2012. It is easily available online to anyone who cares to read it [pdf download here] . But the relatives of those aboard Danny FII had to wait six years for Panama to first file the report with the IMO, and then another several months for it to be made public (and only after sustained pressure from seafarers’ unions and the British government). No wonder the International Chamber of Shipping last year suggested that shipping could learn something from aviation authorities, and expressed a need to stop flag states interpreting the IMO guidelines “with considerable latitude”.

Why do accident reports matter? Because although ships will continue to sink – the ocean will continue to defeat some of them – the toll of loss should not be increased by the pressures of commerce, by seafarers exhausted by their job or by old, corroded ships. Port inspections had found 29 deficiencies in Danny FII in 2009 alone, including widespread corrosion, but she was classed as safe. Shipping is a vast, complicated and wonderful industry without which modern life would be unthinkable and unthinkably different. It can do better.

So, I’m going to keep my flying mantra, although I know it’s skewed risk perception. I know I’m more likely to be killed behind the steering wheel of my car than in a plane or a ship. I’ll learn to steer my perceptions in another direction, like the young British radio officer, sitting in a lifeboat after the ship he was on was torpedoed in 1942, who asked a Dutch crewman how far the nearest land was. “Two miles away,” said the man. “Straight down.”

Rose George is the author of Deep Sea and Foreign Going: Inside Shipping, the Invisible Industry That Brings You 90% of Everything, published by Portobello. Buy it for £11.99 at bookshop.theguardian.com

- Water transport

- Ferry travel

- Globalisation

- Air transport

Skipper of capsized cargo ship 'probably felt pressure to keep sailing'

Daring rescue of fishermen seconds before boat sinks off Isle of Lewis

Cargo ship’s crew presumed dead after vessel sinks off northern Scotland

Sunken cargo ship the Cemfjord located

Comments (…), most viewed.

How Many Yachts Sink Each Year? Here’s What The Data Says

From leisurely sailing trips to luxury vacations, yachts have become a popular way to explore the worlds seas.

But despite their popularity, the data shows that many yachts sink each year, making them one of the most dangerous vessels on the water.

In this article, well explore the scope of the problem, the causes of yacht sinking, who is most at risk, and the impact of yacht sinking.

Plus, well provide safety tips for yacht owners and what the data says about how many yachts sink each year.

So, if youre an avid yacht owner or just curious about this topic, read on to find out more.

Table of Contents

Short Answer

It is difficult to estimate exactly how many yachts sink each year, as many incidents go unreported.

However, the US Coast Guard estimates that there are roughly 500-700 recreational boating accidents resulting in sinking each year in the US alone.

Additionally, it is estimated that between 5-10% of all recreational boats are lost each year due to sinking or other causes.

The Scope of the Problem

The exact number of yachts that sink each year is unknown, but it is estimated that hundreds of vessels are lost annually due to a variety of causes.

Most of these losses are of smaller vessels, with the majority of accidents occurring at night and in areas with little to no navigation assistance.

While the causes of these accidents can range from mechanical problems to storms, collisions are the leading cause of yacht sinkings.

These accidents can have serious consequences, including the loss of lives and damage to the environment.

This is why it is important for all yacht owners to ensure their vessels are properly maintained and equipped for safe navigation.

This includes having the proper safety equipment, such as life jackets, flares, and radios, as well as up-to-date navigational charts and a well-trained crew.

In addition to the loss of life, the financial implications of these accidents can be significant.

Depending on the size of the vessel, the cost of a sinking can range from thousands of dollars to hundreds of thousands or even millions.

Damage to the environment can also be costly, as it can take years to clean up the oil and debris from a sunken yacht.

In order to reduce the number of yachts that sink each year, it is important for yacht owners to practice safe sailing techniques and take all necessary safety precautions.

Additionally, yacht owners should regularly inspect their vessels and have them serviced by a qualified professional when needed.

By taking these steps, yacht owners can help ensure their vessels are safe and reduce the number of vessels that sink each year.

Causes of Yacht Sinking

When it comes to the causes of yacht sinking, there are many factors that can contribute to the loss of a vessel.

The most common causes include collisions with other vessels, severe storms, and mechanical problems.

Collisions can occur between two vessels or with a larger floating object, such as a buoy or pier, and can cause significant damage to the yacht.

Severe storms can create large waves and powerful winds that can easily overwhelm a yacht, while mechanical problems can include engine failure, faulty equipment, or poor maintenance.

Additionally, many of these accidents occur at night or in areas with limited navigation assistance, which can make it difficult for captains to safely navigate their vessels.

As a result, it is important for all yacht owners to ensure their vessels are properly maintained and equipped for safe navigation.

Who Is Most At Risk

When it comes to yacht losses, certain types of vessels are more at risk than others.

Smaller yachts and sailboats are particularly vulnerable, as they dont have the same levels of safety equipment and stability that larger vessels have.

Additionally, recreational boaters are more likely to experience an accident due to their lack of experience and knowledge of the sea.

Finally, yachts and sailboats that are not properly maintained or equipped with the latest safety equipment are also more likely to experience an accident.

All of these factors can contribute to the hundreds of yachts that sink each year.

In terms of geography, yachts that navigate in areas with limited navigation assistance (such as in remote parts of the ocean) are more likely to experience an accident.

Additionally, yachts that sail at night or in bad weather are also more likely to sink.

Finally, areas with higher boat traffic are also more likely to experience a yacht sinking, as the risk of a collision is greater.

It is important for all yacht owners to be aware of the risks and take the necessary steps to ensure the safety of their vessel.

This includes having the latest navigation equipment and safety equipment onboard, as well as conducting regular maintenance and inspections.

Additionally, boat owners should also be aware of the potential dangers of sailing in certain areas and take the appropriate precautions.

By following these simple steps, yacht owners can reduce the chances of their vessel sinking and help ensure the safety of everyone onboard.

The Impact of Yacht Sinking

The loss of any yacht, whether large or small, can have serious consequences.

Unfortunately, yacht sinking is not a rare occurrence – it is estimated that hundreds of vessels are lost each year due to various causes.

This can lead to devastating losses of lives, extensive damage to the environment, and costly financial losses.

When a yacht sinks, it can cause extensive damage to the marine environment.

This is because the sinking vessel often releases hazardous materials such as fuel, oil, and other hazardous substances into the water.

This can cause extensive damage to the local marine life, as well as disrupt the normal flow of the ocean.

Additionally, sinking yachts can also cause damage to nearby ships and vessels, as well as any nearby docks or ports.

The loss of a yacht can also be financially devastating.

Yachts are expensive pieces of property and their loss can cause a significant financial loss to their owners.

In addition, the cost of the vessel’s insurance policy, as well as any associated legal fees, can also be costly.

Finally, the loss of a yacht can have serious emotional consequences.

The loss of a beloved vessel can be devastating for its owners, who may have spent years and considerable money investing in their yacht.

Additionally, any loss of life associated with a yacht sinking can be devastating for the families and friends of those lost.

In conclusion, yacht sinking is a very serious issue, and one that can have serious consequences.

Additionally, yacht owners should always be aware of the potential risks associated with sailing, and take the necessary precautions to minimize the risk of sinking.

How to Reduce the Risk of Sinking

Yacht owners should take steps to reduce the risk of their vessels sinking.

This includes using the proper safety equipment and performing regular maintenance on the vessel.

Additionally, yacht owners should ensure they have the necessary navigation skills and knowledge to navigate safely.

It is also important to make sure the yacht is equipped with life-saving devices such as life jackets, flares, and a life raft.

The United States Coast Guard recommends that all vessels have a minimum of three life jackets and a personal flotation device for each person aboard.

Additionally, flares should be stored in a waterproof container that can be easily accessed and used in case of an emergency.

Yacht owners should also review and adhere to all local, state, and federal navigation regulations.

These regulations can vary by region and may include areas such as speed limits, navigation channels, and restricted areas.

Additionally, yacht owners should be familiar with basic navigation techniques such as chart reading and piloting.

Finally, yacht owners should be aware of the weather conditions in their area and plan their voyages accordingly.

They should check weather forecasts before setting out and be prepared to make changes or even cancel their trip if the conditions are not favorable.

Additionally, yacht owners should be aware of the dangers of storms and take necessary precautions to stay safe.

Safety Tips for Yacht Owners

Yacht owners must take safety seriously, as even the most well-maintained vessel can become a casualty of the sea.

Yacht owners should heed the following safety tips to help minimize the chances of their vessel sinking: Ensure your yacht is equipped with the latest navigation tools and instruments, such as a radar, GPS, and chartplotter.

These should be regularly maintained and calibrated to ensure accurate readings.

Make sure your yacht is equipped with the appropriate number of life jackets and emergency equipment, such as flares, fire extinguishers, and a first aid kit.

Always monitor the weather conditions and plan your voyage accordingly.

Be aware of any storms that may be in the area and avoid sailing in rough waters.

Have a proper check-in procedure with the local Coast Guard or harbor master before departing.

Have a designated lookout and designate a person to be in charge of navigation at all times.

Make sure your yacht is properly maintained and serviced.

Have a professional inspect it regularly and replace any worn or damaged parts.

Make sure your yacht is insured, as this can help in the event of a major accident or loss.

Be mindful of marine traffic and be aware of the navigation rules for the area.

Be aware of the risk of collisions, particularly in crowded areas or at night.

By following these safety tips, yacht owners can help to ensure the safety of themselves and their vessels.

Additionally, it is important for all yacht owners to remain aware of the number of yachts that sink each year and to take the necessary precautions to prevent such occurrences.

What the Data Says

When it comes to understanding just how many yachts sink each year, it can be difficult to get an exact number due to the lack of reporting.

However, data suggests that hundreds of vessels are lost each year due to various causes.

The most common reasons for these losses are collisions, storms, and mechanical problems.

The majority of yacht losses occur in smaller vessels, with most losses occurring at night and in areas with little to no navigation assistance.

This is because these areas are more difficult to navigate and often have hidden hazards that can be difficult to spot.

Additionally, smaller vessels are more vulnerable to storms and collisions, making them more likely to sink.

This is why it is so important for all yacht owners to ensure their vessels are properly maintained and equipped for safe navigation.

By taking the necessary precautions, yacht owners can help minimize the number of yachts lost each year.

In addition to taking the necessary precautions, it is also important for yacht owners to stay informed about the latest developments in yacht safety.

This includes keeping up with the latest regulations and safety protocols, as well as staying informed about the latest technological advances that could help improve the safety of their vessels.

By following these simple steps, yacht owners can help reduce the number of yachts lost each year and ensure that their vessels remain safe and seaworthy.

Final Thoughts

Yacht sinking is a serious problem that affects hundreds of vessels each year.

It can cause devastating damage to property, the environment, and even human lives.

As such, it’s important for all yacht owners to be aware of the risks and take action to reduce them.

This means remaining vigilant while out on the water, taking steps to ensure their yacht is properly maintained, and equipping their vessels with the necessary safety gear.

By following these safety tips, yacht owners can help to ensure a safe and enjoyable experience on the water.

James Frami

At the age of 15, he and four other friends from his neighborhood constructed their first boat. He has been sailing for almost 30 years and has a wealth of knowledge that he wants to share with others.

Recent Posts

Does Your Boat License Expire? Here's What You Need to Know

Are you a boat owner looking to stay up-to-date on your license requirements? If so, youve come to the right place! In this article, well cover everything you need to know about boat license...

How to Put Skins on Your Boat in Sea of Thieves? (Complete Guide)

There is a unique sense of pride and accomplishment when you show off a boat you customized to your exact specifications. With Sea of Thieves, you can customize your boat to make it look like your...

How Often Do Sailboats Capsize & Sink?

Last Updated by

Daniel Wade

May 12, 2023

Key Takeaways

- Try to stay in the boat’s center for the best stability while sailing on smaller boats

- Make sure you have a working bilge pump before heading out to sea

- Many boats sink at the boat ramp due to collisions or other pilot errors

- A sunken boat cannot be saved without additional assistance

- Breaking waves could be dangerous in rough conditions that help capsize boats

Sailboats are designed to float but there are times when disasters happen that could change that. So how often do sailboats sink?

Each year on average, roughly 200 sailboats capsize and sink, which is less than you would imagine for the amount of boats on the water. If you are dinghy sailing, these typically capsize but do not sink. According to US Coast Guard reports in 2020, there were 211 boats that capsized and sank.

After careful analysis, boat sinking is a lot less common compared to a hundred years ago. Thanks to proper education and technology, sailors have adapted to safer sailing experiences.

Table of contents

What is the Likelihood of a Boat Capsizing and Sinking?

Boats capsize and sink for a variety of different reasons. If you know how to avoid those situations, you will likely be much safer and still have a working boat. Boats can capsize and only a select few are able to keep the boat from sinking.

US Coast Guard Statistics

The US Coast Guard reported 211 sinking boats in the year 2020. These numbers help shape an average for the number of sinking boats within a year.

Most of these accidents were user error, while a handful happened at the dock. The point is, no boat is safe from capsizing and sinking.

Type of Boat

When looking at ships, these are much higher sinking occurrences at two a week. There are a lot of vessels that go missing, so it is believed that many are sunk. It is estimated that thousands of boats sink each year but the type of boat matters in those statistics.

Understanding the Types of Capsizing That Leads to Sinking

There are two types of capsizing that boaters need to know. These are referred to as a knockdown or a turtle.

Knockdowns are also called flips in dinghy sailing. This is when the sails and mast are touching the water and the boat rests at a 90 degree angle.

Dinghies and catamarans can recover fairly easy from this situation. On a dinghy, the crew members should stand on the centerboard to help balance the weight of the boat. For a small catamaran, you would need a line on the upper hull to help pull.

Boats with keels will act a bit different depending on the situation in a knockdown. The crew can often add their weight to the side needed, but water pouring in certain spots may be too much to overcome.

A turtle is when a boat completely turns upside down and is likely going to sink. Dinghies and small catamarans can still turn things around from this situation, provided the crew is able to move the boat to a 90 degree angle from the added weight to the centerboard.

If you have a boat with a keel, this will need further assistance from a professional to help right the boat. Some boats are self-righting, but it varies on the type of keel and boat design. With any other type of vessel that turtles, you will likely need further assistance.

What Causes a Capsized Boat?

Many factors influence a boat to capsize and sink. Most of these should be common knowledge, but it is important to point out these situations so that sailors are better informed.

Flooding is the number one cause for ships to sink. As more water enters the boat, the more weight it adds.

Depending on where the water is coming in at will affect the weight distribution of the vessel. This causes the boat to lean or dive down quickly.

Collisions with an object or the ground can cause water to flood the boat. Depending on how bad boat hits something makes a difference on how fast the boat will take on water. This also affects the weight distribution, making the boat less stable and to potentially flip.

Larger boats are more susceptible to collisions since they require more time to safely come to a stop. Keep in mind that you can still do the same in a smaller boat.

Stability has Suffered

Multihull sailboats have much better stability than monohull boats. Sailboats with keels are also more stable.

If your boat is neither of those, you likely have less stability and could potentially capsize. With dinghy sailing, these are designed to move back and forth in the wind. This causes the boat to flip since it has less stability than others boats.

Bad Weather

Poor weather is the main cause of a sailboat or any vessel to capsize and sink. Since the ocean can be unpredictable in combination with weather, it creates a scary situation if the weather happens to be bad the day of sailing.

Pilot Error

A lot of times people make mistakes whether they are influenced by alcohol or something else. This is no different for operating a sailboat and the pilot makes a mistake.

Sometimes a pilot misreads the current situation on how rough the waves are and continues to sail when near a port. Other times it means failure to respond to dangerous situations due to lack of experience on the water.

Avoiding Preventative Maintenance

Sailboat owners need to routinely make adjustments and make sure the boat is working properly. Skipping out on maintenance could mean your boat does not function the correct way and you could capsize during unplanned conditions.

How to Prevent Capsizing and Sinking

A boat capsized is not a pretty sight while sailing and hopefully you never have to experience it. A lot of people believe that proper care can make sailboats unsinkable.

However, that is simply not true. Here are some tips to stay afloat in your sailboat and how to mitigate the risk.

Leave the Centerboard Alone

In boats that have a retractable centerboard you should always leave it all the way down while the sails are up. In the event you have run aground do not raise the centerboard. If you need to move the centerboard at all you must lower the sail to help lower your risk of capsizing.

Stay Seated

You should try your best to stay seated in smaller boats that tend to have a lot of influence in weight shifts. The weight shift messes with the boom or other parts of the boat needed to navigate safely.

Be Aware of the Wind

You should always keep your head on swivel for the latest wind changes. Sailors that can effectively monitor the wind and how it affects your boat will be one step ahead of any potential capsizing danger.

What to Do if Sailboats Tip Over?

No matter if you are a yacht owner or pilot on a sailboat, there are ways to help prepare for when a boat is tipping over. If your sailboat were to tip over, you should:

- Try to account for everyone that was on board

- Grab life jackets if you are already not wearing them

- Enter sailboat from bow or stern and never the sides

- Sit at bow and help bail water if you can (if applicable)

- Call for help

Related Articles

I've personally had thousands of questions about sailing and sailboats over the years. As I learn and experience sailing, and the community, I share the answers that work and make sense to me, here on Life of Sailing.

by this author

Learn About Sailboats

Most Recent

Affordable Sailboats You Can Build at Home

September 13, 2023

Best Small Sailboat Ornaments

September 12, 2023

Important Legal Info

Lifeofsailing.com is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon. This site also participates in other affiliate programs and is compensated for referring traffic and business to these companies.

Similar Posts

Discover the Magic of Hydrofoil Sailboats

December 11, 2023

Hunter Sailboats: Are They Built for Bluewater Cruising?

August 29, 2023

What Is A Furler On A Sailboat?

August 22, 2023

Popular Posts

Best Liveaboard Catamaran Sailboats

December 28, 2023

Can a Novice Sail Around the World?

Elizabeth O'Malley

June 15, 2022

4 Best Electric Outboard Motors

How Long Did It Take The Vikings To Sail To England?

10 Best Sailboat Brands (And Why)

December 20, 2023

7 Best Places To Liveaboard A Sailboat

Get the best sailing content.

Top Rated Posts

Lifeofsailing.com is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon. This site also participates in other affiliate programs and is compensated for referring traffic and business to these companies. (866) 342-SAIL

© 2024 Life of Sailing Email: [email protected] Address: 11816 Inwood Rd #3024 Dallas, TX 75244 Disclaimer Privacy Policy

- Members Area

- Our Members

- Board of Directors

- Annual Reports

- Vessel Registration Process

- Juan de Fuca Transits

- Registration FAQs

- Port of Vancouver Port Pass

- Marine Transportation Security Clearance Program

- Secretariat Services

- Ship Design & Construction

- Prevention + Protection

- Safe Navigation

- Climate Change

- Ports + Terminals

- Policy Positions

- Submissions

- Speeches + Presentations

- Newsletters

- Press Releases + Statements

- Publications

WSC releases report on containers lost at sea

In 2021, international liner carriers’ onshore staff and crews managed 6300 ships, successfully delivering vital supplies worth $7 trillion to the people of the world, in approximately 241 million containers. The World Shipping Council (WSC) Containers Lost at Sea Report covering 2020-2021 shows that containers lost overboard represent less than one-thousandth of 1% (0.001%). However, the past two years have seen a worrying break in the downward trend for losses, with the average number of containers lost at sea per year since the start of the survey increasing by 18% to 1,629.

Triggered by these events, maritime actors across the supply chain have initiated the MARIN Top Tier project to enhance container safety, with WSC and member lines among the founding partners. This project will run over three years and will use scientific analyses, studies, and desktop as well as real-life measurements and data collection to develop and publish specific, actionable recommendations to reduce the risk of containers lost overboard. Initial results from the study show that parametric rolling in following seas is especially hazardous for container vessels, a phenomenon that is not well known and can develop unexpectedly with severe consequences. To help in preventing further incidents a Notice to Mariners has been developed, describing how container vessel crew and operational staff can plan, recognize and act to prevent parametric rolling in following seas. Many more topics, tests and measurements will be undertaken by the project, which will continue reporting on progress and sharing insights on a regular basis through the IMO and other forums.

- Presentations

Latest News

Related posts.

FMC seeking input on container data elements

CILTNA Spring Outlook Conference – May 10

BCMEA and ILWU 514 negotiations hit cooling-off period

Yachting World

- Digital Edition

Could a floating shipping container sink your yacht? How real is the danger?

- Helen Fretter

- May 17, 2017

Millions of containers are shipped around the world. Helen Fretter investigates what the chances of hitting one at sea really are.

It is the stuff of every sailor’s nightmare – the unseen object, lurking beneath a wave, which punctures your hull or smashes your rudder mid-ocean. Never have our oceans seemed so crowded – last year’s Vendée Globe was peppered with reports of single-handed racers smashing into ‘UFO’s (unidentified floating objects), often at high speed, in remote regions, with devastating effects.

But do containers represent a genuine hazard? There is an acute awareness of the impact debris has on the marine environment, yet an apparent lack of current data on how many containers fall overboard – and what happens to them when they do.

There is no requirement for shipping lines to sink, track or retrieve containers lost offshore, so their positions are almost entirely unknown. Sailors who suffer a mid-ocean impact usually have little evidence of what they hit.

The risk may be minuscule, but it is almost impossible to quantify.

‘Like a car accident’

Mike Sargeant was delivering a Farr 52 from the UK to Las Palmas via Cascais last autumn when they collided with something that damaged the yacht’s 3.6m draught keel.

“We were probably about two days out of Las Palmas,” Sargeant recalls. “We had good winds, and it was about 0130, pitch black around 400 miles off Madeira.

“We were doing about 8 knots, which was quite slow really – we had been surfing at around 17-18 knots. I was helming on the port wheel, and it was like a car accident.

“The yacht just went BOOM, and stopped dead. The collision basically threw me off the wheel, it broke one of the spokes of the carbon wheel, and it threw everyone onto the deck.

“We all picked ourselves up quickly and looked at each other. The skipper was shouting, ‘Have you got steerage? Have you got steerage?’.

“I had nothing, but we weren’t moving. We checked the boat from bow to stern. We couldn’t see any leaks – mind you, the Farr 52’s a pretty wet boat anyway.

“Everyone was pulling up sole boards and running through launching the liferafts. Once it was obvious we were steering straight with no apparent damage to the rudder we continued on our way.”

Sargeant says the boat stopped dead before seeming to roll over something on a wave.

“When we got to Las Palmas as soon as we could we sent divers down and they photographed the keel. The bulb is 3.6m below the water level and it had taken a big chunk out of the keel, trashed all of the leading edge and cracked the hull as well.”

Was it a container they collided with?

Sargeant feels all the evidence points to that: “It was something hard and it had given us a huge hit. We were sailing in a high traffic area, and had seen plenty of container ships out there.”

G1K086 Cargo ship sail to Miami port, Florida, USA

How many shipping containers are lost at sea each year?

Almost everything you see, are wearing, or have eaten recently, was transported in a shipping container at some stage. Ninety per cent of goods traded around the world are shipped on the oceans, and there are around 5-6 million containers at sea at any one time.

Yet finding reliable data on how many containers actually fall overboard is a challenge. The widely quoted figure of 10,000 containers lost every year [1] was the basis for reports by organisations ranging from Friends of the Earth to the US Congress. But the World Shipping Council (WSC), a trade body that represents 90 per cent of the global shipping industry, disputes that number [2].

Based on surveys of its members the WSC reported that for the years 2011, 2012, and 2013 there were around 2,683 containers lost each year [3]. Combining that data with surveys going back to 2008, the WSC reports that excluding ‘catastrophic events’ the number of containers lost every year is a mere 546.

However, the data is several years old, and based on voluntary responses, so can it be relied upon?

“Bearing in mind the volume of shipping going on these days, and the accountability of shipping from an environmental impact, if there was more than this going on in the industry we’d know about it,” comments Jonathan Ridley, head of engineering at Southampton Solent University, who is an authority on the industry.

“It’s pretty obvious when a ship arrives in port if containers are damaged or missing, or there’s a stack leaning over. It’s a reportable event.

“If there is an accident with material damage to the ship or pollution the Master and owner have to report the accident for investigation, so I feel quite confident that that’s a realistic figure.”

The littered ocean

However, the stakes are rising. The global shipping industry was hit hard by the 2008 economic crash. In the search for profitability, many lines have launched larger, slower ships – at this scale the cost savings on fuel for running just a few knots slower can be immense.

Now, following the extension of the Panama Canal last year, the latest generation ‘neo-Panamax’ ships have a 49m beam and can bear a vast load of around 9,600 40ft containers.

In 2013 the MOL Comfort broke up in the Indian Ocean, shedding just under 4,300 containers, the biggest single loss ever. As even larger, slower ships carry more containers for longer, potentially making them more vulnerable to storms, a ‘catastrophic event’ could see more than twice that number of metal boxes and their contents released in a single incident.

A major loss in 2014 highlighted just how many containers may already dot the seabed. On 14 February the Svendborg Maersk lost 517 units off Ushant.

Unusually, the French authorities requested Maersk to locate all of the containers.

“They did this unilaterally, and it went way beyond what the IMO expects,” explains Toby Priestly, who has designed a device to sink containers that fall overboard. “They said, ‘We have fishermen in these waters dragging nets along and we need you to plot where every single one of these containers is.’

“So suddenly there was a liability attached.”

Using the same weather modelling software as the Maritime and Coastguard Agency, Priestly plotted the current and weather conditions in the area at the time for 96 hours (at least one container was beached 96 hours after it was lost). This gave a search area of over 9,000 square nautical miles.

Maersk chartered a side-facing sonar ship, and within just a few months reported that it had located some 500 containers.

“Or at least, they found over 500 containers in the area which they searched, which is one of the busiest shipping lanes on the planet,” explains Priestly.

With no way of identifying the source of each container, Priestly points out, there is no way of knowing whether they were the same units which fell from the Svendborg Maersk , or simply indicative of how many containers litter the Channel. Around a dozen containers were also found floating in the weeks following.

Almost all containers that go overboard will sink – eventually.

“They could sink within days, or they could be several months still afloat, it depends on the type,” comments Solent University’s Jonathan Ridley.

“All have doors with rubber seals and when their rubber seals start to break down you’re going to get water in. The containers’ major structure is in their corners – the side panels have a minimum thickness of 1.6mm, which is not a lot for steel.

“So if a container falls off the side of a vessel the twisting torsion on it is probably enough that the container would fail.”

He adds that a loaded container with moving cargo inside is likely to suffer a loss of structural integrity fairly quickly in waves.

Refrigerated containers, known as ‘reefers’, are tightly sealed, insulated units used to transport perishable food, and are likely to float for months. Meanwhile, if the door seals are unbroken, containers carrying light, high value cargo such as smartphones, each wrapped in protective layers of Styrofoam and inflatable packaging, could potentially float indefinitely.

One myth Priestly debunks is the notion that containers can float just below the sea’s surface.

“I did a lot of tank tests on this, and that is actually physically impossible. It might be that a wave washes over it, and it can float very low in the water, but once a container actually goes beneath the surface of the sea, the air inside the container gradually gets compressed and gets less buoyant, so it sinks.

“But it could be just a couple of inches above the surface, and if it’s filled with the right amount of polystyrene, it could stay there forever. “

Exaggerated risk

So how likely are you to encounter one? The spate of collisions reported by competitors in the Vendée Globe focussed the mind of many sailors on the unseen dangers apparently lurking.

Only one competitor reported a suspected collision with a shipping container, with Thomas Ruyant’s Le Souffle du Nord pour Le Projet Imagine cracking around him after what Ruyant reported as “an exceptionally violent” bang, some 250 miles south of New Zealand.

We contacted his team to see if they had been able to learn more about the impact, but were unable to get a response.

At the speeds racing yachts now travel, a crash into a marine mammal can cause a catastrophic impact which has all the violence of hitting a lump of steel, as Kito de Pavant’s onboard video from his collision with a sperm whale in the Vendée shows.

Guillaume Evrard, deputy race director for the last edition of the Vendée Globe, says that race organisation teams rely on MRCCs to report any hazards on the course. In around a decade of working on race organisation, he has never received a warning of any shipping containers on the route.

Organisers of the Clipper Round the World Yacht Race which has seen more than 4,000 people compete in ocean stages, say none of their boats has ever had a close encounter with one – the nearest being in 2012, when the fleet was diverted after a container ship hit a reef off New Zealand.

World Cruising Club reports that in 30 years of transatlantic rallies and other events, with more than 200 boats crossing the Atlantic each year, there have been no confirmed incidents of a yacht colliding with a container.